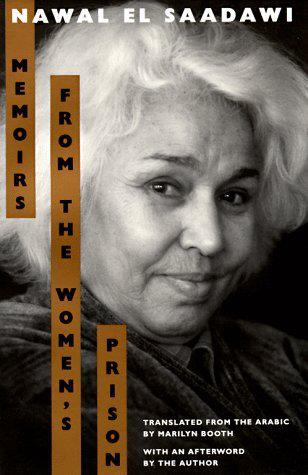

This year I have invited people to participate in an Arab Writers in Translation Reading Circle. Last month, several friends and I met to discuss Egyptian writer Nawal El-Saadawi’s 1983 Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, an account of her two months in confinement on orders of Anwar Sadat in 1981.

When reading Nawal, I was reminded of Pierre Hadot’s description of the philosophical school of the Cynics: “They did not fear the powerful, and always expressed themselves with provocative freedom of speech [parrhesia].” Among the eight of us who met to discuss Nawal’s book, we were each impressed by her strong, brave, defiant spirit.

Born in a rural village, she was from a young age determined to make a life for herself different from all those around her, both female and male. In the first chapter of Memoirs, she admits, “At every stage of my life I have obeyed only that voice coming from my deepest self.” [6] That obedience her led to question religious, political, social, sexual, economic, and male authorities and hierarchies.

Early in her medical career in 1962, she spoke up at the National Conference for the Popular Forces at which Gamal Abdel Nasser was present. Taking the side of the peasants, she was seen by the assembled powerful as “unknown young woman, without position, title, prominent family or clique.” [112] Three words were written down next to her name: “Uncalled-for-boldness,” and since that time the Interior Ministry started a file on her and her name was put on a black list.

Many other middle-class women were arrested at the same time Nawal was. They were perplexed: Why did the police violate their homes? Why had they been arrested? Why weren’t they charged with anything? Rather than sink into passivity and endless fretting, Nawal writes, “Yet, something would move inside me suddenly, something built into me, the rebel, angry and revolting against this gravity, this submission to worry and grief. Rebelling against passivity and lack of movement, resisting defeat and pessimism, so that I would say: ‘We will not die, or if we are to die we won’t die silently, we won’t go off in the night without a row, we must rage and rage, we must beat the ground and make it shudder. We won’t die without a revolution!’” [36] Those last two sentences anticipate the collective defiance seen throughout the Arab world over the last fourteen months.

Nawal had been arrested while working on a novel (later published as The Fall of the Imam). For her, writing was her life, the pen more important than anything or anyone else. Yet being imprisoned wasn’t going to stop her from pursuing her vocation. The only time for the crucial solitude was late at night and before the morning call to prayer came: “After midnight, when the atmosphere grows calm and I hear only the sound of sleep’s regular breathing, I rise from my bed and tiptoe to the corner of the toilet, turn the empty jerry can upside down and sit on its bottom. I rest the aluminum plate on my knees, place against it the long, tape-like toilet paper, and begin to write.” [129]. But in a prison cell that was ultimately for political offenses, writing posed the greatest danger. She would not relent.

But writing outside the prison cell also had its consequences. Nawal is disappointed that, while many people from around the world protested her arrest, some writers held back: “Not even a single [Egyptian] writer from among my colleagues and friends published one word in defense of freedom of opinion and speech. They shrank inside their homes, taking refuge in silence and inaction, or traveling abroad, or sharing with others in playing on the strings which give pleasure to the holders of power.” [140] She wasn’t disappointed, however, at the solidarity and camaraderie she found among the women of various backgrounds in the prison.

It seems the “crimes” Nawal and the others committed had to do with their criticism of Sadat’s deal with Israel at Camp David. During her stay in prison, Sadat was assassinated, and within a month of his death, she was free. In her afterword to the 1994 American edition of the book, she writes, “When I came out of prison there were two routes I could have taken. I could have become one of those slaves to the ruling institution, thereby acquiring security, property, the state prize, and the title of ‘great writer’; I could have seen my picture in the newspapers and on television. Or I could continue on the difficult path, the one that had led me to prison. I chose the second way, and so I came to be under permanent threat, not only of imprisonment but indeed of death.” [202] In the biblical tradition, these two paths were taken by the court prophets and the prophets, the latter whom tradition esteemed over the former.

Sadat thought that he could silence, punish, and intimidate Nawal and her comrades in the women’s prison. What he unwittingly did was thereby help to generate a work—Nawal’s memoirs—that would guarantee his infamy.

Nawal El Saadawi, Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, American Edition 1994, University of California Press, translated by Marilyn Booth.

Our next meeting is to discuss Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories: Wednesday 25 April at the Center for Survivors of Torture and War Trauma (1077 South Newstead, 63110). Potluck dinner at 6; discussion at 6.45.