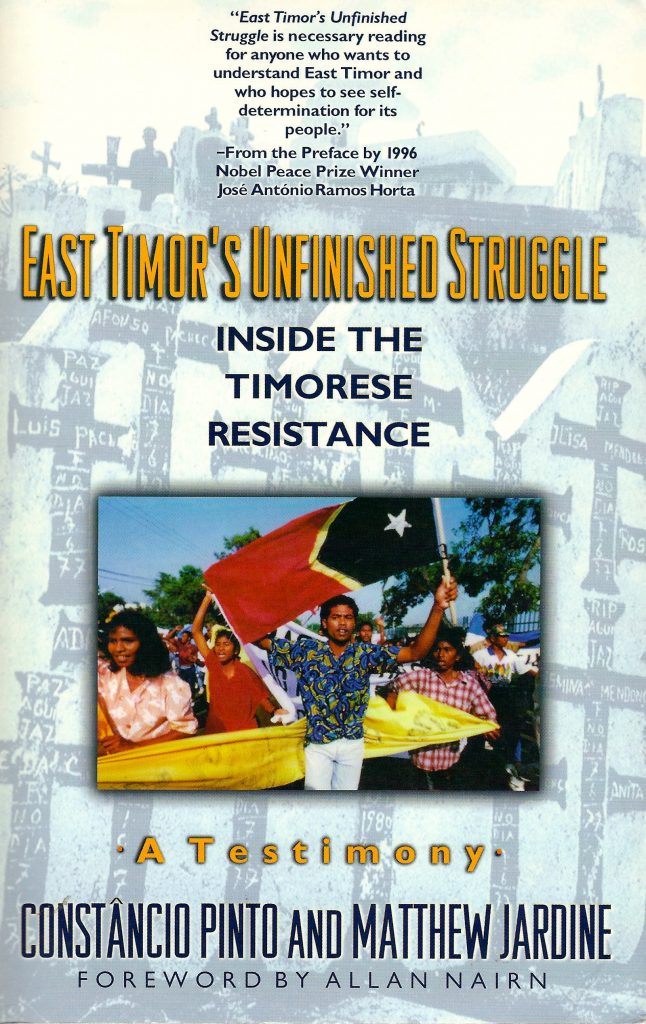

East Timor’s Unfinished Struggle: Inside the Timorese Resistance —

A Testimony. By Constâncio Pinto and Matthew Jardine.

South End Press, $16.00.

After over two decades of relentless persecution, the people of East Timor received a belated but major acknowledgment of their suffering when the Nobel Committee awarded its 1996 Peace Prize to Catholic Bishop Carlos Belo and activist/diplomat José Ramos-Horta.

For many Americans, the awarding of the Nobel Prize to these two courageous individuals may have sent them to an atlas — where is East Timor? Given our lack of familiarity with the country, American Catholics surely have much to learn from this people from a small island, a former Portuguese colony, that was invaded and annexed by Indonesia in 1975. The present book by Constâncio Pinto and Matthew Jardine is a welcome contribution to the urgent project of increasing American understanding of and sympathy for the Timorese struggle for self-determination.

The savvy investigative journalist Allan Nairn contributes a riveting preface on East Timor, including the Santa Cruz massacre in 1991 at which he was present and during which he had his skull cracked by Indonesian soldiers. Matthew Jardine provides a very useful historical and political analysis of East Timor’s long struggle for independence, covering the centuries of Portuguese colonial occupation as well as the Indonesian occupation. He pays particular attention to the U.S. role in providing a range of ideological, diplomatic, and military assistance to Indonesia.

Constâncio’s story is, quite simply, a powerful bearing witness to the dignity and determination of his people. In 14 chapters, he tells the tale of his growing up in East Timor, the fateful Indonesian invasion, and the extensive suffering of a people under siege. He details his work with the military resistance which he soon gave up for the important position of the secretary of the underground’s executive committee. He also recounts his work with Xanana Gusmão, the admired leader of the military resistance. In a gripping part of his story, Constâncio is captured by the Indonesian military, is tortured, and, for some time, acts as if he is playing along with the authorities, supposedly having seen the error of his ways of seeking independence for his people.

Constâcnio played crucial roles in preparing for a Portuguese delegation that was scheduled to arrive in East Timor in 1991; however, the Portuguese did not come, disappointing the Timorese who had hoped they would be able to communicate their agony to those from the outside world.

That publicity came anyway, with the popular demonstration at the Santa Cruz cemetery in the capital city of Dili in November 1991. This display of defiance and courage turned into a major bloodbath as the Indonesian soldiers fired upon the civilian demonstrators. With U.S. journalists Nairn and Amy Goodman present, the story got out to the international press, although it should be noted that there had been plenty of other atrocities in past years that never made it to the major U.S. media.

Constâcnio could not play the dangerous game of double-agent for much longer. He tells of going underground before going into exile in the United States, where he is currently pursuing his degree at Brown University and speaking about the cause of East Timor. He was eventually united with his wife and child whom he had to leave behind in East Timor.

At frequent points in the book, he reveals his own spirituality, a combination of both his ancestral, indigenous religion and a devout Catholicism. About the role of the Catholic Church in East Timor, Constâcnio states that “[t]he Church is helpful because the Church is the people. If there are no people, there is no church. And when the people suffer, the Church also suffers. The Church is the only East Timorese institution that is outspoken about the atrocities committed by the Indonesian army in East Timor. The East Timorese put their hope and trust in the Church. It’s the only institution that we can complain to about our suffering. The Church has made the resistance even stronger. It gives inspiration to the East Timorese to continue to resist and fight” (p.238).

In reading this plain-spoken testimony, I thought of another witness to atrocity, Elie Wiesel, who once said, “Anyone who does not engage actively today in keeping these memories [of the Holocaust victims] alive is an accomplice of the killers.” It is sobering to realize that Americans, by our ignorance, amnesia, or silence, are such accomplices to the Indonesian killers and their patrons in the U.S. government.

Matthew Jardine’s contribution to this book also contains valuable lessons for relatively privileged U.S. church people. He met Pinto in 1993 and over several years collaborated with him to produce this testimony. In addition, Jardine has visited East Timor and reported and written widely on the continuing repression by Indonesia, as well as the abiding U.S. connection over many years. Jardine’s own story is one of listening in compassion to Pinto’s testimony and being moved to significant commitment and action.

On a personal note, I met Constâncio Pinto in 1993 while he was speaking with three other young Timorese students on a tour through the San Francisco Bay Area. I introduced him to Oakland Bishop John Cummins, a close friend of Bishop Belo, and many of us were moved by his dedication to his people. We owe a debt of gratitude to Constâncio and Matthew Jardine for this searing and inspiring work, which reminds us of the price ordinary people are willing to pay for freedom and independence. Not least, East Timor’s Unfinished Struggle is a call to change our government’s policy that has been all too cozy with one of the worst violators of human rights in recent memory.

published in National Catholic Reporter