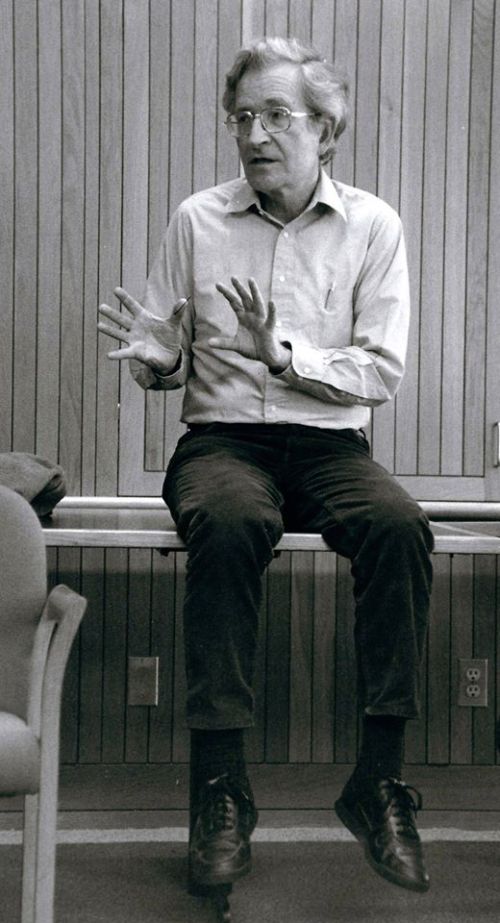

Noam Chomsky, Turning the Tide: U.S. Intervention in Central America& the Struggle for Peace, South End Press, 1985

The real victims of “America’s agony” are millions of suffering and tormented people throughout much of the Third World. Our highly refined ideological institutions protect us from seeing their plight and our role in maintaining it, except sporadically. If we had the honesty and moral courage, we would not let a day pass without hearing the cries of the victims. We would turn on the radio in the morning and listen to the voices of the people who escaped the massacres in Quiché province and the Guazapa mountains, and the daily press would carry front-page pictures of children dying of malnutrition and disease in the countries where order reigns and crops and beef are exported to the American market, with an explanation of why this is so. We would listen to the extensive and detailed record of terror and torture in our dependencies compiled by Amnesty International, Americas Watch, Survival International, and other human rights organizations. But we successfully insulate ourselves from this grim reality. By so doing, we sink to a level of moral depravity that has few counterparts in the modern world….

This 1985 analysis was quite important for me; in fact, it precipitated an intellectual conversion, as it provided a coherent view of the political world in light of my experiences with Sanctuary, Witness for Peace, and the Pledge of Resistance. In Chapter 1, Free World Vignettes, Chomsky exposes the hypocrisy of the US government and media by focusing on the real story — ignored or denied — of suffering in Central America, those “miseries of traditional life” which are tolerable to Jeanne Kirpatrick and others. He analyzes the challenge posed by El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala and their popular movements and the responses made by their governments and the US; in a phrase, the struggle for human rights unleashed an outburst of state terror designed to put the lower orders back in place. The Reagan Administration and human rights were at loggerheads, as even Oscar Romero strongly opposed Carter’s aid to the Salvadoran military regime, and Reagan upped all antes, including the infamous defense of Gen. Rios Montt. Chomsky also has a section reviewing at some length on the contribution of mercenary states, particularly Israel, as Yoav Karni notes: “The Israelis may be seen as American proxies in Honduras and Guatemala.” Plus, there are some startling connections, as I indicated in my dissertation, on evidently non-problematic relations among the US, Israel, and neo-Nazis (how after 1967, Israel used the services of Klaus Barbie to funnel them arms).

In (2) The Fifth Freedom, Chomsky uncovers the roots of such misery in Central America, namely, the need to preserve the 5th and most important freedom, the freedom to rob and exploit. Of course, the rhetoric must not reveal this ghastly and greedy reality. But we must attend to the perception of the planners (Kennan’s famous revelations in 1948) who are ready to use force and brutality to maintain the disparity. Moreover, Latin America is an incident, not an end; we use it for our purposes. In this framework, Nicaragua’s policies are of course interpreted as intolerable crimes.

(3) deals with Patterns of Intervention; we must always defend our sovereignty — in those areas of Central America that contain our resources! As such, we live by the rule of force, and insist that our enemies live by the rule of law. Contemporary state terrorism was born in the 1960s under Kennedy as the armies of Latin America went from external defense to internal security, against the population who were deemed Communist enemies if they dared to raise questions or oppose the status quo. Chomsky has separate sections on how the terrorist system was applied in El Salvador — Carter’s war, the role of Duarte, the move towards “democracy,” and the moving into high gear of the propaganda system and the Salvadoran Army to deal with the rebels (effects to which Elie Wiesel did not witness: tens of thousands of tortured and mutilated victims, the terror of the air war, the physical destruction of the political opposition and the media…); of course, Chomsky recounts the reaction in the US of the liberal media to this successful terror. Then there was the torturing of Nicaragua, with the proxy war, the attempted delegitimation of their elections in 1984, and then other tortures in (Haiti and Guatemala. Throughout, Chomsky reveals the utter contempt of US leaders for human rights, the raising of the living standards and democratization. As pertinent to Wiesel, Chomsky derides the “awesome nobility of our intentions”: “[why do we resort to propaganda?] There are two basic reasons. The first is that reality is unpleasant to face, and it is therefore more convenient, both for planners and for the educated classes who are responsible for ideological control, to construct a world of fable and fantasy while they proceed with their necessary chores. The second is that elite groups are afraid of the population. They are afraid that people are not gangsters. They know that the people they address would not steal food from a starving child if they knew that no one was looking and they could get away with it, and that they would not torture and murder in pursuit of personal gain merely on the grounds that they are too powerful to suffer retaliation for their crimes. If the people they address were to learn the truth abut the actions they support or passively tolerate, they would not permit them to proceed. Therefore, we must live in a world of lies and fantasies, under the Orwellian principle that Ignorance is Strength.”

In (4) The Race to Destruction, NC picks up where he left off in The Fateful Triangle: the threat of global war. He here provides a broader context for situating the US fixation on Central America. He reviews the Cold War years, an early version of his more extensive revisioning in World Orders Old & New: how the US is always and only defending the national territory, defending Western Europe, and containing the Soviet menace. A startling section is “containing the anti-fascist resistance: from the death camps to the death squads” which is mandatory in any future writing on Wiesel, particularly it wasn’t just Barbie’s crimes during W.W.II but his crimes since with crucial Western, US support in Latin America. He also analyzes the indispensable role of the Pentagon system, its various flimsy pretexts and the evidence that shows that the US planners have not in the least been concerned about real security.

In (5) The Challenge Ahead, Chomsky reviews the conservative counterattack given the “crisis of democracy” that broke out since the 1960s, with attacks on labor, against rights, independent thought. The ultimate target throughout is the public mind, which must be controlled. Lessons that remain valid are the need to go outside the system through direct action, which raises the cost of aggression — “Without these actions, lobbying the Congress, letter writing, political campaigning and the like would have proceeded endlessly with as much effect as they had in 1964, when the American people voted overwhelmingly against escalation of the war in Vietnam, voting for the candidate who at that time was secretly preparing the escalation that he publicly opposed.” Also, “to concentrate all energies on delaying an eventual catastrophe while ignoring the causal factors that lie behind it is simply to guarantee that sooner or later it will occur.” He ends the book with this sobering comfort: “There are no magic answers, no miraculous methods to overcome the problems we face, just the familiar ones: honest search for understanding, education, organization, action that raises the cost of state violence for its perpetrators or that lays the basis for institutional change — and the kind of commitment that will persist despite the temptations of disillusionment, despite many failures and only limited successes, inspired by the hope of a brighter future.”

–written near the end of my dissertation on Elie Wiesel, March 1997