No wonder, as Martin, Dianne and I have been making our way through Anatoli Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel, that a phrase that I first heard in 1987 has flittered through my mind recently.

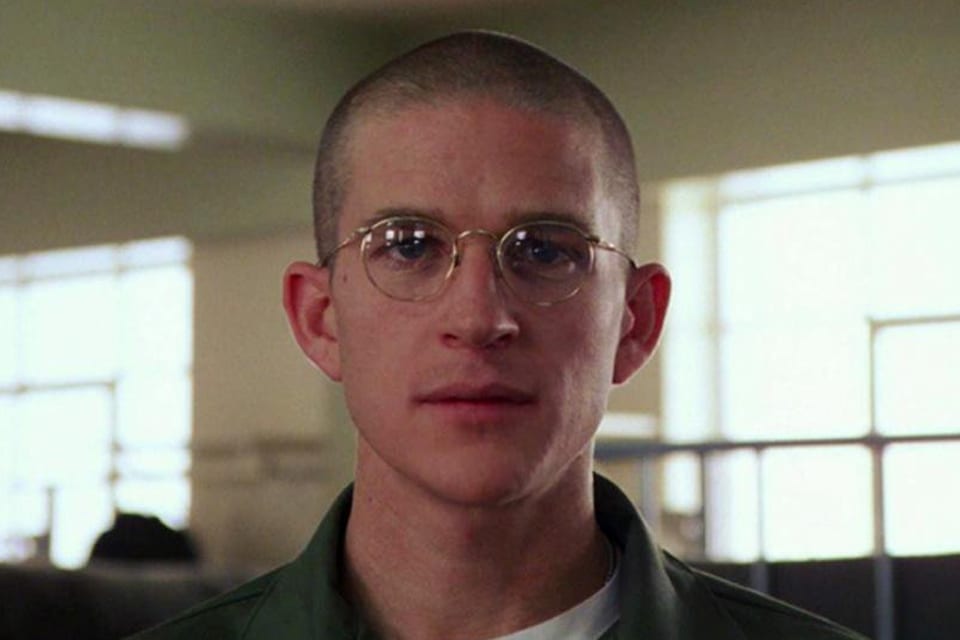

Pogue Colonel: Marine, what is that button on your body armor?

Private Joker: A peace symbol, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Where’d you get it?

Private Joker: I don’t remember, sir.

Pogue Colonel: What is that you’ve got written on your helmet?

Private Joker: “Born to Kill”, sir.

Pogue Colonel: You write “Born to Kill” on your helmet and you wear a peace button. What’s that supposed to be, some kind of sick joke?

Private Joker: No, sir.

Pogue Colonel: You’d better get your head and your ass wired together, or I will take a giant shit on you.

Private Joker: Yes, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Now answer my question or you’ll be standing tall before the man.

Private Joker: I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir.

Pogue Colonel: The what?

Private Joker: The duality of man. The Jungian thing, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Whose side are you on, son?

Private Joker: Our side, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Don’t you love your country?

Private Joker: Yes, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Then how about getting with the program? Why don’t you jump on the team and come on in for the big win?

Private Joker: Yes, sir.

Pogue Colonel: Son, all I’ve ever asked of my marines is that they obey my orders as they would the word of God. We are here to help the Vietnamese, because inside every gook there is an American trying to get out. It’s a hardball world, son. We’ve gotta keep our heads until this peace craze blows over.

Private Joker: Aye-aye, sir.

In a fury I swung my arm up and threw the fish down on the ground with all my strength, so that it bounced like a ball, but it still went on wriggling and jumping. I went in search . of a stick and found a rough piece of wood which I pressed down on the perch’s head while it went on staring at me with its silly fish-eyes-and I proceeded to squash and hack and dig at that bead, until I bad gone right through it. And in the end it stayed quiet. Babi Yar, 326

I used to get especially angry if people tried to persuade me to admire great statesmen. Maybe I missed a great deal as a small boy because of this. But all the same I never found myself being carried away by accounts of Alexander of Macedon or Napoleon Bonaparte, not to mention any other of our great benefactors. This almost morbid loathing for dictators, who invariably had their columns and columns of victims in the background, interfered with my reading and learning and even prevented me, paradoxically enough, from appreciating the greatness of such people as Shakespeare and Tolstoy. When I read Hamlet I would try to reckon up how many wretched servants had to be working for him so that be could carry on unhindered, torturing himself with his questions. When I read about Anna Karenina I used to wonder who had to sweat away to ensure that she could eat and drink her fill, and always be beautifully turned out. She was another of those parasites absorbed in her own woes. Somewhere at the back of my mind I realized that it was rather foolish of me to act like this, but I could not overcome it. One’s environment determines one’s mental outlook. The only figure in literature who was always and still remains near to me is Don Quixote. Babi Yar, 334-345