“I Belong to Chomsky”

Spring 1994 was blooming in the Bay Area. We participated in a Good Friday demonstration at the Lawrence Livermore nuclear laboratory with Steve Kelly and our Pax Christi friends. The following week, we welcomed Noam Chomsky to our campus. On several occasions, we had both heard Chomsky fill the huge lecture hall on MIT’s campus when Mev and I lived in Cambridge in 1990-1991.

Chomsky had a slew of engagements. He was kind to include the GTU in his overbooked schedule, which has been overbooked for the last decade and a half, as he is constantly on the road, all over the world, giving talks. That’s what he does best: explicate the nature of U.S. foreign policy in a way that ordinary people can understand. This has long earned him scorn and dismissal by those with the proper PhD political science credentials. When I interviewed him in Cambridge, he said to me, “When I enter the Harvard faculty club, you can feel the chill from those professors.” And even though he personally had no use for organized religion, he still had strong appreciation of the Catholic militants in Latin America whom he had met and stayed with throughout Nicaragua on a speaking tour there in the mid-1980s. His anarchist convictions were interwoven with his personal practices: Even though he was known world-wide as a linguist and philosopher of first rank and a radical political activist, he was eminently down-to-earth. He talked in as many monosyllables as possible because he believed that political commentators so regularly tried to make their specialty arcane and above the heads of folks. Chomsky was different. So, although I was delighted that he responded to my late letter of invitation, I wasn’t so surprised. He’s a mensch, I told Mev. Or, as my friend Angela, a Reform rabbi, exclaimed, “He’s my rebbe!”

“Well, maybe now we can have him over for dinner. How long will he be here?” In resurrecting a plan she had while we lived in Cambridge to have Noam over for a simple dinner and chat, she was as relentless in thinking that we could entertain the world-famous Chomsky as Chomsky was relentless in pursuing the perfidy of American power in Central America. As if! I was back to my old standoff-ishness.

“Mev, I think he’s got barely enough time to take a shower in the five days he’s here, much less have dinner with us. Besides, Bob Lassalle-Klein told me the Catholic Worker wants to have him and his wife over for dinner before his fund-raiser talk for them that Friday night. So, then, we can visit with Noam.”

“At last, it will be so nice to get together,” she commented, as if she were talking about Steve Kelly.

I was responsible for picking up Chomsky from his previous appointment in San Francisco, a radio talk show interview. I arrived 15 minutes early, not wanting to allow some traffic snafu to throw off our event. When he came out of the interview room, clad in his brown corduroy jacket and blue oxford cloth shirt and khakis, I introduced myself and said, “You’re so generous to come over to Berkeley to speak to us. We’re all looking forward to it.”

“Great. Think we have time for a sandwich before the talk?”

“Sure, let’s get to Berkeley and hang out before the talk at 1:00 p.m.”

As we drove over the Bay Bridge, Chomsky was quite interested in who the audience was for his talk. I felt somewhat apologetic, too, since I’d heard him say in interviews that he is often asked to speak on intellectuals and political responsibility. It seemed so elementary that it was amazing this issue was in such need of clarification. “Yes, our group of Doctoral Students for Social Responsibility tries to keep things lively on campus, even though most of us are swamped with preparing for exams or working on dissertations. This talk is open to the broader community. We’ll have Haiti activists, Central America Sanctuary workers, disarmament folks, as well as professors, lots of students, maybe some administrators, and so on.”

“So, what exactly do you want me to speak about?”

I was caught off-guard by his asking me that question. What, didn’t he have it all down-pat in that genius brain of his? “I mean,” he clarified, sensing some apprehension in me, “What do people need or want to hear?” I told him that I thought his basic framework of how intellectuals behave and how they ought to act is one that would be most appropriate to the academic environs, which, given its utter simplicity, would nevertheless be a challenge though not totally unfamiliar.

We went down to Euclid to a cafe and we ordered falafel sandwiches, while he reminisced about being in Berkeley where he lectured in the mid-1960s. Soon thereafter, over 100 people jammed into the GTU Board Room for Chomsky’s talk on intellectuals and poltical responsibility. It was a wake-up call to us to find ways here to think, write and speak critically about our own national reality, as the Salvadoran Jesuits sought to do in their own context.

He was scheduled to give a talk on Thursday evening on the Middle East, but since I was going to the Catholic Worker dinner and talk later on at our church, St. Augustine’s, I thought I could pass. Plus, I had my exams coming up in less than two weeks, and Mev had recently been experiencing these vexing eye aches, which required her going to the doctor.

At the UC Berkeley opthamologist office that Thursday, the doctor told us what might be causing the eye aches: “Stress.” Mev wasn’t satisfied.

“Tell me, doctor, what’s the worst thing this could be?”

“The worst?”

“Yeah, the absolute worst.”

“It could be a brain tumor. But I wouldn’t worry about that. We need to set you up with a neurologist next week. He’ll be able to give you a better take on this problem.”

Early the next morning, Mev awakened me.

“Mev, what time is it?”

“I belong to Chomsky.”

“You what?”

“I belong to Chomsky.”

“Oh, you had a dream about Chomsky. I’m going back to sleep, dear.”

She clasped my arm and responded, “I belong to Chomsky.”

“That’s fine, Mev, you belong to Chomsky. It’s 5 a.m. I’m going back to sleep.”

I turned over and tried to close my eyes. It was way too early to get up, even to study for my imminent exams.

Then Mev shook me: “I belong to Chomsky!”

“Mev, what are you talking about,” I barked, as I agitatedly turned on the light.

She looked at me with a furrowed brow and quivering lips. She entreated once again, “I … belong … to … Chomsky.”

“Mev, you were pissing me off, now you’re scaring me. What do you mean you belong to Chomsky?”

She held out her hands, palms up, as if to say she meant me no harm: “I belong to Chomsky…”

“Mev, something’s terribly wrong here.”

And then, after a couple of minutes more of this repetition, she was finally able to blurt out something new: “Marko, I don’t know what was happening. I couldn’t stop saying that. I was trying to tell you something, but that’s all that would come out.”

I was stunned and thought back to an evening a month before, when Mev had tried perplexingly and in vain for 30 minutes to tell me to take breaks when I was studying. There was something on the tip of her tongue that she desperately wanted to tell me, but, to my bafflement, she could neither it say nor let go of the desire to say it.

“Would you call that neurologist for me? I’m so scared.”

“At this hour?”

“Yes, I’ve got his home number, the Cal doctor gave me both numbers.” She got up and went into the study and brought back her day planner phone directory.

“Mev, who calls a doctor at 5:30 in the morning?”

“Mark, this is serious.”

“OK.”

Naturally, I woke up Dr. Friedberg. As he shook off his grogginess, I tried to explain to him what had just happened.

“Do you think this is something psychological with your wife?”

“Psychological? What do you mean?”

“Is this a psychological problem, or do you think this is physical?”

“Dr. Friedberg, this is physical.”

“All right, then. I will set up an EEG for her this morning at Alta Bates. I will call you back shortly and let you know when.”

On the basis of that EEG later that morning, Dr. Friedberg recommended that Mev get an MRI. “When can I get one?” she asked him.

“I can try to get you one for early next week.”

“No, no, no, Doctor, I want one today. Can you see about getting me in sooner?”

“I’ll see what I can do.”

That evening, we skipped the dinner with the Catholic Workers and Chomsky because we were awaiting for a phone call from the MRI center. At 8:30 p.m., we received word that they had an opening.

Mev’s best friend, Maria, had been over to our apartment and, for the comfort of the familiar, we had just started to watch the Bergman and Bogart movie, Casablanca, which we had seen so often in Cambridge. We later drove down to Telegraph Avenue where the clinic was located, and Mev had her MRI. A physician was called over from his dinner in San Francisco to look at the scans. Mev overheard him use the word “lesions” when he was looking at them.

She turned to stare at me: “Mark, I have a brain tumor.”

“Mev, we don’t know yet what you have.”

“Doctor, isn’t it true, you used the word ‘lesions’.”

“I think it would be best to see Dr. Friedberg in the morning and let him interpret these with you. Yes, there are lesions here, but he’s the one you will need to speak with about what your options are.”

It was 10 p.m. Just down the street, Chomsky was probably into his second hour of questions and answers at the Catholic Worker fund-raiser. But Mev and I had just entered into an entirely new world.

—The Book of Mev

Our Rebbe

For years I read him to get a bearing

On the atrocities the U.S. enabled in Central America

I wrote my Master’s thesis on him

On Israel/Palestine and liberation theology

When I met him at his MIT office

He patiently answered all my questions

In Berkeley he spoke at the theological consortium

And had dinner with the Catholic Workers

He sent his condolences

After he heard Mev had died

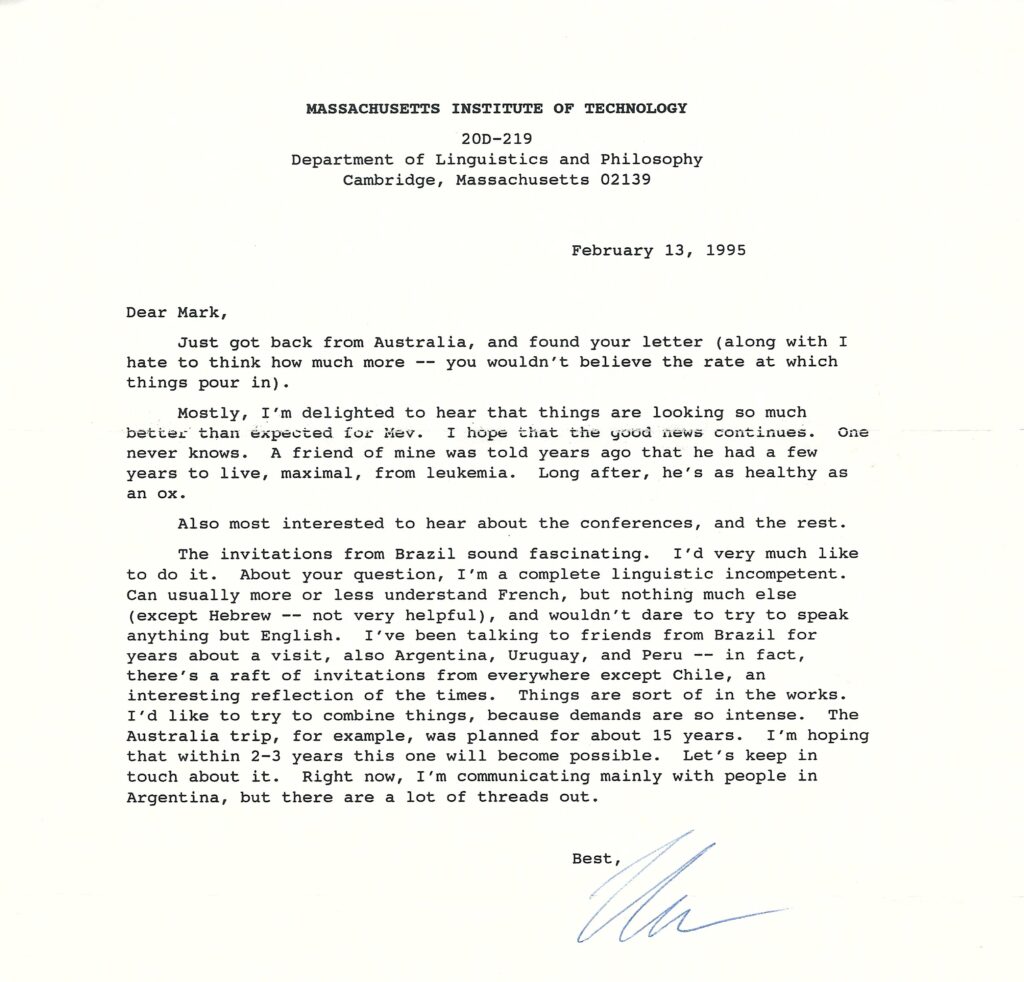

I corresponded with him over the years

Once he replied with a six-page, single-spaced letter

I was one of thousands of nobodies who wrote him

He took the time to answer us

A student wanted to bring him to campus

I said, “Email him”

“Email him?”

“Sure”

So he did

The next day he heard back

My friend, a Reform rabbi, once said

“Chomsky’s my rebbe”

A Letter

This page is part of my book, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.