1967

Today’s Email: “Thank you for signing up for the [New York Times] Vietnam ’67 newsletter. Over the course of the next year, we’ll examine the participation of the United States in the long war in Southeast Asia. The Vietnam ’67 newsletter will arrive in your inbox weekly.”

“Participation”

“Long War”

Journalist Bernard Fall writing in 1967: “It is Viet-Nam as a cultural and historic entity which is threatened with extinction. While its lovely land has been battered into a moonscape by the massive engine of modern war, its cultural identity has been assaulted by a combination of Communism in the North and superficial Americanization in the South.”

“Extinction”

“Moonscape”

Two Teachers

For two of my teachers

I give thanks:

Cao Ngoc Phuong

Khuu Vinh Ngoc Thuy

I first read Phuong’s autobiography

Learning True Love:

How I Learned & Practiced Social Change in Vietnam

When it was published in 1993

I assigned it for years

In a Social Justice course at SLU

The social work majors appreciated her

Phuong was a social worker without an MSW

I wanted the students

To become acquainted with lines like these

“A living example often can have a stronger effect

Than thousands of theoretical teachings and rules”

“What really inspired me was working In the slums…

Most of the time I went alone I never felt tired doing this work

It was a joy

To be able to help”

“My dear brother is gone

But his spirit lives on in my heart

And in the hearts of so many of his friends

Who continue his work

From time to time I still say ‘hello’ to him

When I see myself behaving the way he did

It seems that a part of him

Has been reborn in me”

In 2007 a new edition of Learning True Love appeared

Updating her and Thich Nhat Hanh’s return to Vietnam

After four decades of living in exile

Mostly in France

I had Thuy in class

In spring 2006

We meet up several times a year

She often brings me gifts

(Much art hanging on the walls in my home

I received from Thuy)

She has long touched me

With her calm and courage and kindness

She will deny it (predictably)

She will tell me to ask her sister Thoa for an alternative point of view

We went out to celebrate her graduation from SLU

She didn’t see why I made such a big deal about it

It was a big deal

Coming to this country at the age of 8

Graduating at 22

With a 3.7

Setting an example

For her younger siblings

She later tutored me some in Vietnamese

And was always so positive

She introduced me

To the intricacies of Vietnamese poetry

She thinks deeply about the meaning

Of this precious life

Thich Nhat Hanh quotes the sutra

“The one contains the all”

When I look deeply at Thuy

I get a glimpse of the vast interbeing

Of the United States people

And the Vietnamese people

Her parents in their 20s

During the war years

Their suffering after the war

Their journey to this country

War and peace

Victory and defeat

Home and exile

Grief and relief

I am

Because Thuy is

For these two teachers

I join my palms

I see the Buddha

In each of them

They live out the Dharma

The way of understanding and love

They are part of my sangha

Bringing harmony and awareness

Vietnamese Voices

In 2012 President Barack Obama In 2012 President Barack Obama signed on to a Congressionally approved on-going 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, for each year of the war’s duration. We are currently commemorating 1969.

Though we call it “the Vietnam War,” U.S. Americans are, obviously, at the center of our remembrance. We recall our veterans, our leaders, even, now and then, our dissenters. I will explore how we can learn about ourselves and our former allies and enemies by considering reflections from three Vietnamese people intimately familiar with the war. Many of us know of the Zen Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh. He lived in then South Vietnam until he went into exile in the mid-1960s. Far fewer people know of scholar and writer Viet Thanh Nguyen, who was born in South Vietnam and came to the U.S. with his family as refugees in 1975. His novel The Sympathizer won a Pulitzer Prize in 2016. I venture that hardly anyone knows of Dang Thuy Tram, who was a doctor from North Vietnam who went South to assist in the struggle against the U.S. invaders. Her diary, Last Night I Dreamed of Peace, was published posthumously and came out in an English translation in 2007.

Please join us Sunday 31 March

Potluck dinner begins at 6:00

I begin sharing at 6:45

At the home of Andrew Wimmer

Arco Avenue

The Good News of Public Libraries

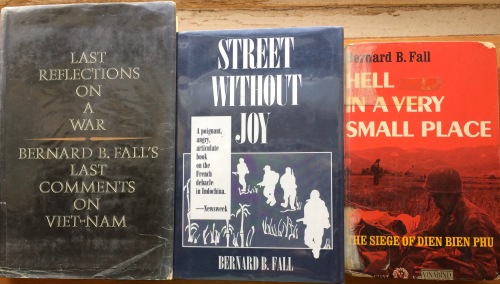

This afternoon I walked eight blocks north to the Central West End’s Schlafly Library where I picked up three books by Bernard B. Fall, whom Noam Chomsky once described as “the most respected analyst and commentator on the Vietnam War”—Last Reflections on a War, Street without Joy, and Hell in a Very Small Place: The Siege of Dien Bien Phu. The new trainee at the circulation desk said, “All these are very old books, look at the condition they’re in!”

Remembrance, Responsibility, Reparations

Ariel S. Garfinkel, Scofflaw: International Law and America’s Deadly Weapons in Vietnam

With the recent passing of Senator John McCain, it’s clear how hard it is for many Americans see what we’ve done in the world. It’s much easier to see what others have done to us, in this case, the Vietnamese who held McCain captive and tortured him. Despite Trump’s demurrer that McCain was no “hero,” the week-long mourning and focus on his death and life speaks otherwise.

Ariel Garfinkel can help us better see who we are and who we’ve been. In her timely, informative, and piercing book, Scofflaw: International Law and America’s Deadly Weapons in Vietnam, she brings attention to the damage the U.S. did to the Vietnamese people both during the war and since, with its unexploded ordnance (UXO), and the lethal defoliant, Agent Orange. Because of these, people continue to suffer and die in excruciating ways.

Regarding UXO, Garfinkel writes, “Children are still being maimed by cluster bombs, their parents are still dying from grenades and mines, and the full removal of remaining live ordnance at the rate of success over the past two decades will reportedly take hundreds of years more.” As for Agent Orange, it is true that the U.S. government has acknowledged the significance of Agent Orange when it comes to care for our veterans, yet the government is unable and unwilling to acknowledge its responsibility for the death and devastation its has caused the Vietnamese people. According to the author, “an estimated 400,000 Vietnamese died as a result of exposure to the chemical sprays.”

The way forward, Garfinkel contends, is for the U.S. citizenry to make use of international law to push the government to act on its obligations, including making reparations to the Vietnamese people. Garfinkel has no illusions about intentional law: “The serious lack of teeth in the body and promising framework of human rights created over the past several decades cannot be denied. Even as these words are written, people suffer misery and death because states continue to undermine their obligations to human rights.”

I was reminded by Garfinkel’s analysis of the 2004 documentary, The Corporation, based on Joel Bakan’s book. Like the corporations who manufactured Agent Orange, the U.S. government cannot, or, at least up to this point, has not admitted guilt and acted on its responsibility. Whoever occupies the Oval Office will assert that the U.S. is the indispensable world leader and champion of international law. But, as Garfinkel states, by evading the laws appropriate to U.S. use of munitions and Agent Orange, the U.S. will “[remain] an international outlaw.”

Back in 2012 President Obama inaugurated an on-going commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War. In official activities, one can be sure that the issues Garfinkel examines will not be mentionable. It’s instinctive for us to think about how the U.S. military suffered in those years; it’s rare for us to try to imagine what the Vietnamese went through because of U.S. policy: the “mothers whose sons never returned; children whose fathers can no longer provide for the family; families with little or no economic means to feed themselves due to destroyed homes, burned fields, and missing family members; and the permanently impaired, particularly the families whose infants continue to be born with gruesome deformities due to the permanent alteration of their parents’ and grandparents’ DNA by exposure to chemical defoliants.”

Ariel Garfinkel helps us to remember. May her book persuade more U.S. citizens to act responsibly in a movement for cleaning up UXO and working for reparations for those harmed over several generations.

Chan Khong’s Secret

Sometimes I feel overwhelmed. But I try to work one day at a time. If we just worry about the big picture, we are powerless. So my secret is to start right away doing whatever little work I can do. I try to give joy to one person in the morning, and remove the suffering of one person in the afternoon. That’s enough.

When you see you can do that, you continue, and you give two little joys, and you remove two little sufferings, then three, and then four. If you and your friends do not despise the small work, a million people will remove a lot of suffering. That is the secret. Start right now.

Including Ourselves

[C]ontemporary war is a bureaucratic and capitalistic enterprise that requires its bored clerks, soulless administrators, ignorant taxpayers, contradictory priests, and encouraging families. If we understood that a war machine is a pervasive system of complicity that requires not only its front line troops but also its extensive network of logistical, emotional, and ideological support, then we would understand that all the politicians and civilians who cheer the war effort or simply go along with it are, one and all, rear echelon motherfuckers, including, perhaps, myself.

–Viet Thanh Nguyen

Share the Wealth with Thuy Khuu: A Life in Design

Have you noticed that toilet paper only comes in circular rolls? Has it occurred to you that it can be in other shapes, square for instance? What would happen then?

Every day, we interact with countless of products, literally! We see them, hear them, feel them, smell them, and even taste them in some cases! We are surrounded by design and living in a designed world. Yet, we usually don’t notice it until something goes wrong, then we question, “Who in their right mind would design this thing?! ”

My name is Thuy. I am a woman who has encountered her midlife crisis a decade or two early. At this Share the Wealth, please allow me to share with you the story of how I’ve found design, what design means to me, and what I would like to do with design.

Join us Wednesday 28 December

Potluck dinner begins at 6:00

Thuy begins sharing at 6:45

At the home of Mark Chmiel and Joanie French

Chouteau Avenue

Forest Park Southeast

This page is part of my book, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.