As my 61st birthday approaches, I’ve noticed that I have recently been going back to authors and works I read many years ago. For example, I’ve been reading Thomas Merton’s Asian Journal, William D. Miller’s A Harsh and Dreadful Love (a history of the Catholic Worker Movement), and Dan Berrigan’s late 90s commentary on the prophet Isaiah.

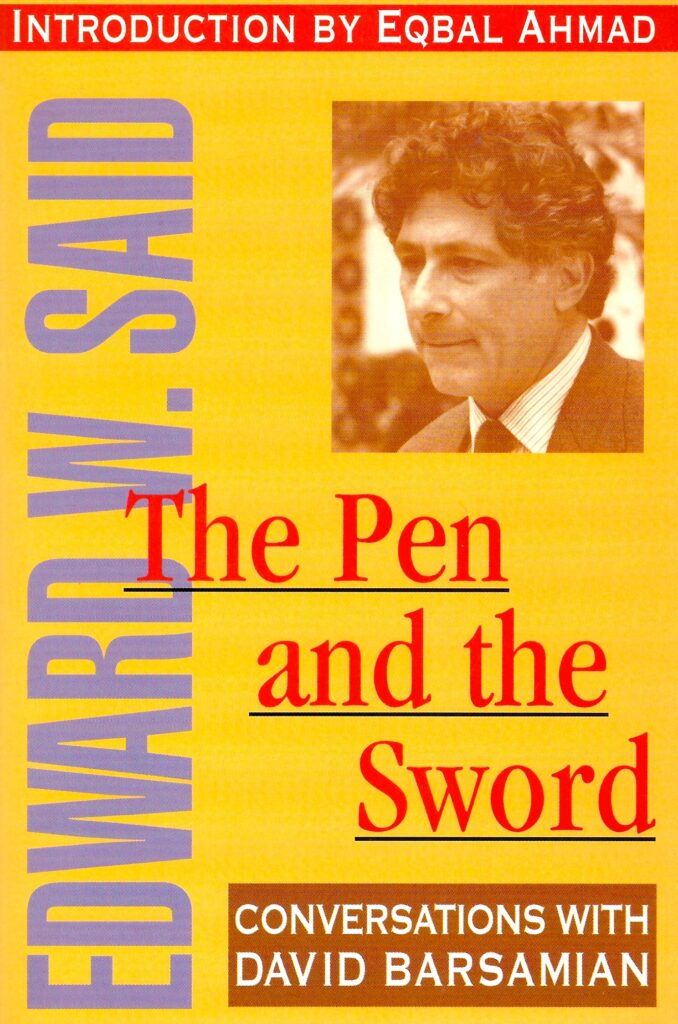

Just today I was rereading David Barsamian 1994 collection of interviews with Edward Said. I first benefited from David’s work with Alternative Radio when I would buy his cassette tapes (I’m talking the 1980s here) of lectures by and interviews with Noam Chomsky. This was during the time in Louisville when many of us were involved with Witness for Peace, the Sanctuary Movement, and the Pledge of Resistance.

The Pen and the Sword came out in 1994 (Common Courage Press) and it provided an excellent introduction to Said’s work. One exchange particularly struck me today about an encounter Said had—

DB: Given the history of the Jews and the creation of the Israeli state, because of their historical experience with persecution and suffering and holocaust and death camps, should one feel that Israelis and Jews in general should be more sensitive, should be more compassionate? Is that racist?

ES: No, I don’t think it’s racist. As a Palestinian I keep telling myself that if I were in a position one day to gain political restitution for all the sufferings of my people, I would, I think, be extraordinarily sensitive to the possibility that I might in the process be injuring another people. And one of the great puzzles to me, and it’s a deep mystery, I must say, is how few, comparatively, Jews and Israelis I’ve met who, beyond embarrassment and discomfort when they meet a Palestinian, feel a sense of remorse and compassion for creatures who are going through in many respects what they went through. What’s more disturbing, creatures who are going through what they went through but now because of them, because of what has been done by Israeli Jews to Palestinians, Palestinians are going through what Jews did before them. I’ll never forget the almost shattering effect on me when Matti Peled, who once was a reserve general in the Israeli army three or four years ago was in America and I invited him to Columbia. He’s a man I respect and admire a great deal. He was describing his activities: he was running for the Knesset. Subsequent to that he was elected to the Knesset. We had lunch, and he was telling me about his activities. I turned to him and said, “Matti, why do you do this? It’s extraordinary.” He said, “In one word, remorse. I feel remorse.” It had such a powerful effect on me that even when I think on it I choke up, that a man would say such a thing. It filled me with admiration and regard for him, and yet at the same time I keep wondering why so few people feel that remorse.

While I was reading Said on remorse, my friend Hedy Epstein immediately came to mind. As a Jew who grew up in Germany, Hedy increasingly gave time and energy to solidarity work with the Palestinian people beginning in the fall of 1982 after the Lebanon war and continuing until just before she died five years ago. Remorse led to responsibility. Her memory remains a blessing.