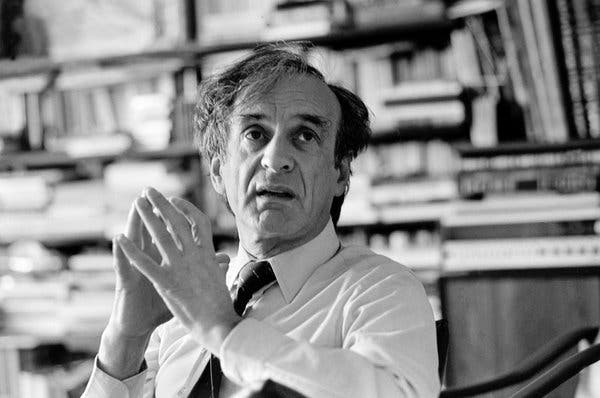

Elie Wiesel, Somewhere a Master: Further Hasidic Portraits and Legends

This is Elie Wiesel’s third of four installments thus far on his favorite Hasidic teachers, the ones whose tales enchanted him in his childhood, the ones whose stamp on him is becoming increasingly clearer to me, the ones representative of an entire culture that was destroyed, an entire culture whose innocence, depth, and piety Wiesel celebrates. I recall those lines from From the Kingdom of Memory: “Why do I write? To wrest those victims from oblivion. To help the dead vanquish death.”

And yet on how lectures become a book, there is some false advertising here, because this book is inclusive (and nowhere is this stated) of Four Hasidic Masters, the Notre Dame lectures. I noticed a few slight phrase changes, but the lectures of Pinhas, Marukh, the Seer, and Naphtali are essentially the same. So, there are chapters on Aharon of Karlin, Wolfe of Zbarazh, Moshe-Leib of Sassov, Meir of Premishlan, and the School of Worke. There is the same basic afterword, which is really where he speaks to what interests me, to wit: “In retelling these tales, I realize once more how much I owe these Masters. Sometimes consciously, sometimes not, I have incorporated a song, a suite, an obsession of theirs into my own fables and legends. For me, the echoes of a vanished kingdom are still reverberating. And I have remained the child who loves to listen. More than ever, we, today, need their faith, their fervor; more than ever, we, today, need to imagine them helping, caring — living.”

I’m glad I am reading these texts because, to recall Bob Lassalle-Klein’s kind admonition to get to know Wiesel on a human level, it does give me an appreciation for him and his culture. I am sympathetic with his attempt to beat back death, to remember the sages and dreamers that so shaped him and his family, to institute his own remembrance of things and wonders past.

And yet, apart from the personal, human level, there is the political, ethical level at which I am working in this dissertation/first book project. And this other way of looking at Wiesel is: his romanticism, nostalgia, exalted sense of Jewish innocence were then intensified by the immense trauma he and the Jewish people underwent, thus preventing him from seeing or admitting the dark side of Israeli power, the present course of Israel as an occupier, and the betrayal of a Jewish tradition of ethics (someone like Israel Shahak took a different path). The Hasidic movement he champions in Somewhere a Master was predictably apolitical since it it was premodern, while the Zionists were political in an eminently modern way, as the Messiah won’t come and protect or deliver the Jews, they must do it themselves. Does Wiesel contradict himself? Very well, he contradicts himself, he contains premodern, modern, and postmodern multitudes.

— 12 June 1996