Dear Friends in the Sangha,

I first encountered The Miracle of Being Awake (later published as The Miracle of Mindfulness) in 1982, when a monk from the Abbey of Gethsemani gave me a mimeograph of an English translation of a manual for social workers in Vietnam. In the 30 years since then, Thich Nhat Hanh has applied his simple message of mindfulness to many key areas of our lives: The environment, healthy eating, peacemaking, public service, anger, intimate relationships, among many others.

I read one of Thầy’s most recent books, Good Citizens: Creating Enlightened Society, in which he uses Buddhist fundamentals to sketch how we can become better public selves. Seeking a broad audience, neither religious nor not necessarily “spiritual” either, he invites people to consider the Buddhist pragmatism as found in the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and the Five Wonderful Mindfulness Trainings. At 144 pages, the book can be read in a fairly short time; integrating it, however, may require many years of practice.

In encouraging people to become good citizens, Thầy leaves it to his readers to apply these teachings in our own contexts. It is there and then that we may learn a great deal about how good, mindful, compassionate citizens are characterized, at least when they dare to question the prerogatives of the powerful.

For example, here in Saint Louis, two of the most powerful corporations in the country have a comfortable home—Boeing and Monsanto. Their public relations departments will enthusiastically remind us that they are true benefactors to the community since they support our schools, universities, arts, and charities.

Obviously, Boeing is an integral part of the military-industrial complex, which enables U.S. militarism to be without peer in the world. Yet the corporation’s operations are linked to the violation of the first mindfulness training, which calls for reverence for life, and reads as follows:

“Aware of the suffering caused by the destruction of life, I am committed to cultivating the insight of interbeing and compassion and learning ways to protect the lives of people, animals, plants, and minerals. I am determined not to kill, not to let others kill, and not to support any act of killing in the world, in my thinking, or in my way of life. Seeing that harmful actions arise from anger, fear, greed, and intolerance, which in turn come from dualistic and discriminative thinking, I will cultivate openness, non-discrimination, and non-attachment to views in order to transform violence, fanaticism, and dogmatism in myself and in the world.”

Imagine, for a moment, that some local citizens aren’t so impressed by Boeing’s contribution to the commonweal. Suppose they want to help their fellow citizens become more aware of the suffering in the world and so begin a campaign to highlight Boeing’s products, which generates its profits. One part of such a campaign could be a mobile photo exhibition around the city to show the bodily effects of Boeing’s products on expendable peoples in the Middle East and West Asia.

Even assuming that such citizens do the above with some mindfulness, is it likely that the Boeing executives and employees, their allies in the university, and their friends in the community at large will look upon those people as “good citizens”? Or is it more likely that they would be seen as “anti-American” or “soft on terrorism”?

A “good citizen” in Thầy’s mindful sense may be a “bad citizen” from the standpoint of a nation’s dominant power interests. I recall first hearing the expression “a good German” back in the 1980s. Said ironically, it referred to those German citizens who were “good” in that they were obedient, quiet, and passive during the Third Reich.

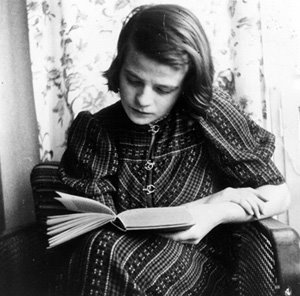

In 1943 in the eyes of the Nazi state, Sophie Scholl and other young members of the White Rose Movement were considered “bad citizens,” nay, traitors, for distributing leaflets calling on their fellow German citizens to oppose Hitler’s tyrannous rule. To many around the world today, the White Rose members are viewed as among the most exemplary citizens in Germany from those horrible years.

“The real damage is done by those millions who want to ‘survive.’ The honest men who just want to be left in peace. Those who don’t want their little lives disturbed by anything bigger than themselves. Those with no sides and no causes. Those who won’t take measure of their own strength, for fear of antagonizing their own weakness. Those who don’t like to make waves—or enemies. Those for whom freedom, honour, truth, and principles are only literature. Those who live small, mate small, die small. It’s the reductionist approach to life: if you keep it small, you’ll keep it under control. If you don’t make any noise, the bogeyman won’t find you. But it’s all an illusion, because they die too, those people who roll up their spirits into tiny little balls so as to be safe. Safe?! From what? Life is always on the edge of death; narrow streets lead to the same place as wide avenues, and a little candle burns itself out just like a flaming torch does. I choose my own way to burn.”

–Sophie Scholl