Hindus make a distinction between what are called upagurus and what are called satgurus. A satguru is what we’ve been talking about here as the guru; it’s the one who is the doorway. … Along the way, however, there are the upagurus. They are teachings for us; they are like the marker stones along the road that say, “Go this way, Go that way.” I think, in fact, that it is much more productive to look at those beings that way—as teachings rather than as teachers. That way, we can take a teaching here and a teaching there and then go on, instead of getting hung up in deciding, “Is this really my teacher?” The whole teacher-trip leads us into making The Big Commitment, and then we sit around judging and comparing and worrying about whether we’ve made the right choice. None of that intellectual analysis is conducive to getting the Bhakti juices flowing.

—Ram Dass, Paths to God: Living the Bhagavad Gita

From one point of view one may call one’s guru every person from whom one has learnt something, no matter how little. But the real guru is He whose teaching helps one toward Self-realization.

—Sri Anandamayi Ma, in Joseph Fitzgerald, The Essential Sri Anandamayi Ma: Life and Teachings of a 20th Century Indian Saint

The outer teacher makes us aware of the teacher within, and to the extent we can be loyal to the outer teacher, we are being loyal to ourselves, to our Atman.

— Eknath Easwaran, The End of Sorrow: The Bhagavad Gita for Daly Living, v. 1

“If you can just manage five minutes a day, then do that. It is important to do whatever you can, no matter how little.”

—Dipa Ma, in Amy Schmidt, Dipa Ma: The Life and Teachings of a Buddhist Master

He would create an entire situation just to teach you. He never gave lectures or taught from scriptures, but he taught through incidents and situations.

—Ram Dass, Miracle of Love: Stories about Neem Karoli Baba

What, then, is an elder? An elder is one who takes your soul, your will into his soul and into his will. Having chosen an elder, you renounce your will and give it to him under total obedience and with total self-renunciation. A man who dooms himself to this trial, this terrible school of life, does so voluntarily, in the hope that after the long trial he will achieve self-conquest, self-mastery to such a degree that he will, finally, through a whole life’s obedience, attain to perfect freedom—that is, freedom from himself—and avoid the lot of those who live their whole lives without finding themselves in themselves.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Swami [Prabhavananda’s] attitude was like that of a coach who tells his athletes that they must give up smoking, alcohol, and certain kinds of food, not because these are inherently evil, but because they may prevent the athlete from getting something he wants much more—an Olympic medal, for instance.

—Christopher Isherwood, My Guru and His Disciple

… and if he threw himself into the monastery path, it was only because it alone struck him at the time and presented him, so to speak, with an ideal way out for his soul struggling from the darkness of worldly wickedness towards the light of love. And this path struck him only because on it at that time he met a remarkable being, in his opinion, our famous monastery elder Zosima, to whom he became attached with all the ardent first love of his unquenchable heart.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

He comes to mind hundreds of times each day, showing some facet, some quality or other, perhaps discriminative wisdom of patience, compassion or emptiness, joy or childlikeness, ancient elderness or jokester-tricksterness. Each time he is a reminder….So each time I think of him and my heart opens, I experience him being there in my life situation with and for me, like an imaginary playmate…

—Ram Dass and Mirabai Bush, Compassion in Action: Setting Out on the Path of Service

I was aware of a strong sexuality in [Swami Prabhavananda] which seemed to be controlled, rather than repressed or concealed. He would remark, quite often and without embarrassment, that some girl or woman was beautiful. His honest recognition of the power of sex attraction and his lack of prudery in speaking of it was a constant corrective to my inherited puritanism.

—Christopher Isherwood, My Guru and His Disciple

Over the years, with encouragement from wonderful teachers, I have found that. rather than blaming yourself or yelling at yourself, you can teach the dharma to yourself. Reproach doesn’t have to be a negative reaction to your personal brand of insanity. But it does imply that you see insanity as insanity, neurosis as neurosis, spinning off as spinning off. At that point, you can teach the dharma to yourself.

—Pema Chödrön, Start Where You Are: A Guide to Compassionate Living

“If you are a householder, you have enough time. Very early in the morning, you can take two hours for meditation. Late in the evening you can take another two hours for meditation. Learn to sleep only four hours. There is no need for sleeping more than four hours.”

—Dipa Ma, in Amy Schmidt, Dipa Ma: The Life and Teachings of a Buddhist Master

Without even saying it, Munindra embodied in his being that it’s OK for you to be whoever you are, yet your goal is to be one with the Dharma…. His style was more to invite you to experiment and experience.

—Mirka Knaster, Living This Life Fully: Stories and Teachings of Munindra

“Mama, my joy, it is not possible for there to be no masters and servants, but let me also be the servant of my servants, the same as they are to me. And I shall also tell you, dear mother, that each of us is guilty in everything before everyone, and I most of all.”

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

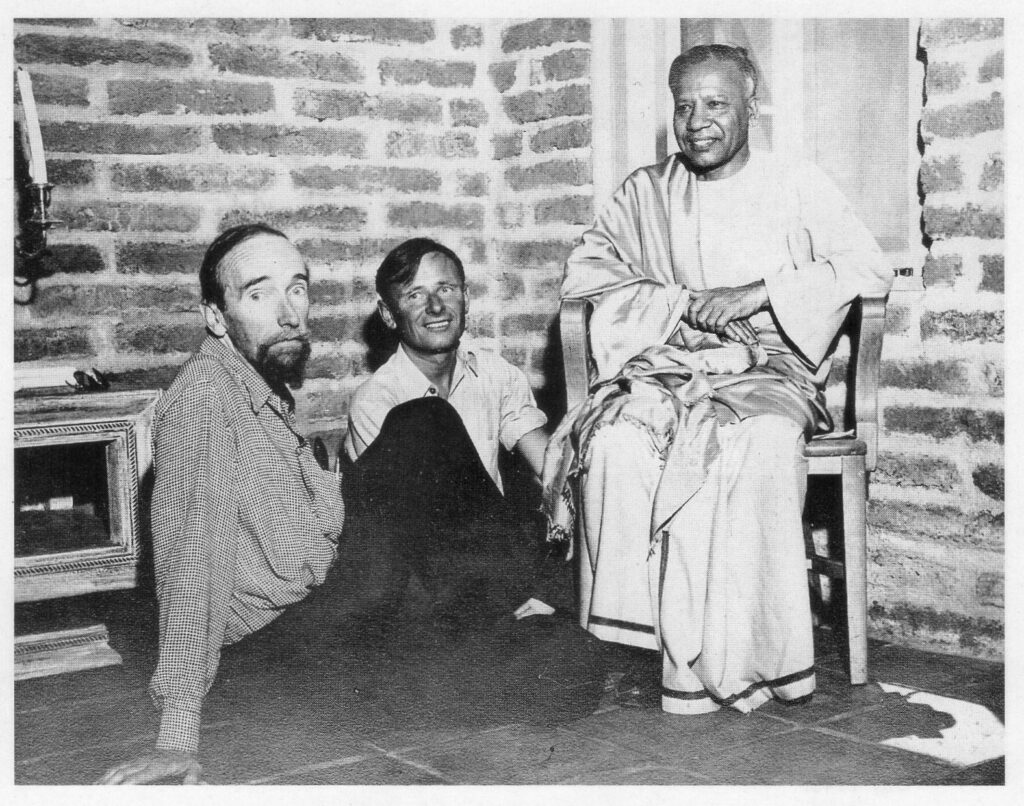

Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood, Swami Prabhavananda