Dear Friends of Saint Louis Mindfulness Sangha,

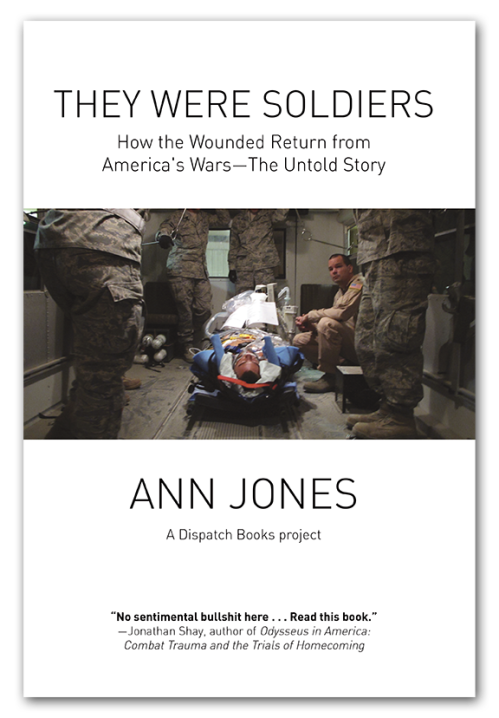

The first of the five wonderful mindfulness trainings emphasizes cultivating reverence for life. The original version of the 12th precept of the Order of Interbeing reads: “Do not kill. Do not let others kill. Find whatever means possible to protect life and prevent war.” For a U.S.-based sangha, these teachings are particularly challenging. In her sobering new book, They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars–the Untold Story, journalist Ann Jones explains why: “No other nation on the planet makes war as often, as long, as forcefully, as expensively, as destructively, as wastefully, as senselessly, or as unsuccessfully as the United States. No other nation makes war its business.” How do we, both as citizens of this nation and as followers of Thich Nhat Hanh’s path of compassion and mindfulness, respond to this obsession with war?

A few friends and I recently met over the course of three winter Wednesday evenings to discuss Jones’ book. We all have known relatives, friends, and students involved in current, recent and distant wars. They Were Soldiers is well worth your consideration, yet I suspect that there will be parts of the book to which you’ll want to close your eyes, and not read another line. Thay reminds us that when difficult emotions arise in us we must return to our breathing. This book is an opportunity for “deep reading meditation.”

You can practice awareness throughout her first chapter, in which she highlights the Mortuary Affairs Unit whose role is to deliver the “remains” of the “fallen” to their next of kin. A member of this unit stated that one could not shake off the stench of death while doing that work. Mortuary Affairs also attempt to minimize the contact soldiers on the ground have with this reality of death. You may recall how death has been out of sight in these last many years of war-making, as we read the following from Jones: “For 18 years, except when a president ignored the ban for a patriotic photo op, Americans were forbidden a glimpse of the war dead coming home because, as [Dick] Cheney must have feared, the sight might have been too much for the sensibilities of American voters who still remembered Vietnam. It might have made them think about the dead: all those formerly real people, those men and women who had fallen, and wonder what for.” Regarding World War II, the deaths of U.S. soldiers from 1941-1945 have been seen by the U.S. populace as a necessary, meaningful sacrifice in the battle against fascism. And the dead from our recent wars?

You can test your ability to remain equanimous as you consider chapter 2 on the fate of the wounded. Jones surveys how the injured soldiers move from the battlefield to the various stages of care, including surgeries, on their way back to the U.S. You will become acquainted with men who become quadriplegics or lose their genitals.You will meet an evangelical chaplain who tries to help the soldiers discover a meaning in their physical and psychological torment. Though Afghanistan may be far from many U.S. people’s concerns, its significance is at the center of many veterans and their families and caregivers, as Jones notes: “All the signatures of the war in Afghanistan are written on [soldiers’] bodies: pulverized legs that probably will be amputated, shrapnel from the blast, concussion, possible traumatic injury to the brain and traumatic shock that might haunt an Afghan or be diagnosed in an American as post-traumatic stress disorder…. This war now is mostly about explosions.”

With chapter 3, on “the new normal,” you can meditate on how arduous it must be for many veterans to adjust to life in the U.S. after boot camp and battle, after seeing their friends injured or killed, or after losing their limbs. Among the issues Jones covers in this chapter are drugs and suicide. A soldier admits, “The drugs helped me in one way because I couldn’t get angry if I wanted to. But I still didn’t feel anything so it wasn’t a solution to what I thought was my biggest problem–that I couldn’t connect anymore with human beings. Even my own family. I wanted to be part of life again.” I’m reminded of something Jean Abbott once said about her work with the women who were torture and war trauma survivors from Bosnia. They’d tell her, “You’re so kind to try to help us. But there’s nothing you can do for us. We’re the living dead.”

Next you can see how much nondiscrimination and compassion you generate for the vets who kill their significant others or the soldiers who rape and harass other soldiers, one of the themes of chapter 4. Jones quotes an Army prosecutor who evidently asked in all seriousness, “Where is this aggression coming from?” Jones gives a partial answer: “in Afghanistan, combat soldiers have been compelled by a ludicrous theory of warfare to walk out daily through landscapes laden with mines and bombs. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder may well be the more accurate diagnosis for captive, powerless, terrified veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, just as it is for thousands of captive, powerless, terrified soldiers who have been raped by their comrades, and for many abused military wives waiting at home.” If war is our national business, it should be no surprise that the violence can erupt at home in myriad ways.

If you can make it to the last chapter on “sacrificial soldiers,” you can ask yourself how and why it is that so many lives have been damaged and destroyed by what Jones calls these “wars of choice. In 1973 psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton published a book on his work with veterans coming home from Vietnam. He wrote of the ghosts of Vietnam that “appear in the form of thousands of veterans returning without limbs, and hundreds of thousands, or even millions, with the unresolved if not irresolvable pain, conflict, and bitterness of the betrayed. They appear also in the form of Vietnamese survivors, whose voices are just dimly beginning to be heard by Americans, bearing witness to the suffering we have caused. And they will continue to appear, above all, in memories and images concerning death and the dead, images that will not easily lead themselves either to healthy absorption or a meaningful survivor formulation.” 41 years later, the ghosts of Vietnam are now being accompanied by those ghosts of Iraq and Afghanistan. They walk among us.

Having covered war for many years, Jones asserts, “War is not natural. We have to be trained for it, soldiers and citizens alike.” Part of our training as citizens is to think in predictably jingoistic terms about the wars and to respond in predictably banal ways of supporting the troops. Being part of a sangha should be a counter-training to this normalization and glorification of war. It may start with reckoning, as Jones has steadfastly tried to do, with the suffering of U.S. soldiers and their families. But it cannot stop there. We must also go on to reckon with the victims of our soldiers and policy-makers, as we spend the rest of our lives finding whatever means possible to protect life and prevent war.

Sources

Thich Nhat Hanh, For a Future To Be Possible: Commentaries on the Five Wonderful Precepts

Thich Nhat Hanh, Interbeing: Commentaries on the Tiep Hien Precepts

Ann Jones, They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars–the Untold Story

Robert Jay Lifton, Home from the War: Learning from Vietnam Veterans