July 2005

It was one month ago that I began to read Whitman in earnest, and, while I still have far to go in prose and poetry, an impression has been made, a fire has been lit, a joy has been savored. Driving with Joanie up from Corpus Christi to Dallas, and then on the Amtrak train back to St. Louis, hour after hour, I read Whitman.

I read Whitman to lessen the grounds for Simone’s scowling about my alienation from nature.

I read Whitman to rejuvenate a vision of what is possible for These States.

I recommend Whitman to friends as as a kindred spirit.

I read Whitman to learn the scourge of war.

I read Whitman to celebrate comrades like Andrew Wimmer and Jean Abbott.

I read Whitman to recall my halcyon adolescent days, both at Trinity and Salem high schools.

I read Whitman to cull and memorize short poems and passages of long ones, so that they may always be with me, and I may be able to summon them as I need them, e.g., “Me Impertube”: “To confront night, storms, hunger, ridicule, accidents, rebuffs, as the trees and animals do.”

I read Whitman to better understand the Beats, especially Ginsberg, especially self-promotion, so I can send out 25 complimentary copies of The Book of Mev.

I read Whitman to encounter again such works as “Song of Myself,” “As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life,” “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” The Sleepers, “Song of the Open Road,” Passage to India and more.

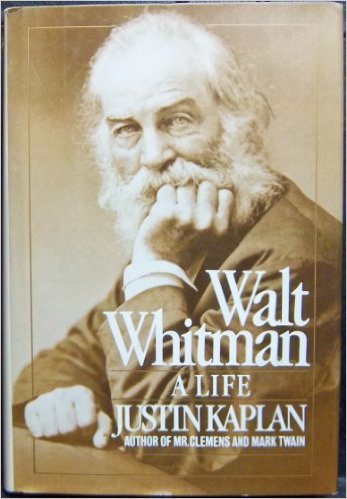

I read a simple poem of Walt’s on Jesus, and read Kaplan: “Whitman, too, identified himself with Christ—‘My spirit to yours dear brother,’ he had written, ‘I understand you’—and lived at the center of a flame-colored cloud that prevented him from seeing himself plain.”

I read Whitman to see a marvel of a man still fucked up by love: What he voiced, he could not have; he, too, was like Ginsberg in mid to late twenties: needy, graspy, and hysterical.

I read Whitman’s bio to discover I am the same, a packrat: “he had kept every imaginable variety of written and printed matter: manuscripts, old letterheads…”

I read Kaplan to get a sense of my possibilities with this second book, how obsessive I could be: “Sometimes he reshaped his past deliberately, just as he reshaped Leaves of Grass over the course of nine editions in order to give his life as well as his work a different emphasis.”

I read Kaplan to get an idea that, if worse comes to worst, I can flat-out imitate Walt: He gave most away of Leaves of Grass to friends and relatives.

I read Kaplan to get another reminder of “hold it all”: “He was to concern himself with ‘the most profound theme that can occupy the mind of man’: ‘the relation between the (radical, democratic) Me, the human identity of understanding, emotions, spirit, etc.’ and the ‘Not Me, the whole of the material objective universe.’”

I read Kaplan to get a critical perspective on the American Bard, who said something absurd like this, in that age of cruel Manifest Destiny: “we forget that God has given the American mind powers of analysis and acuteness superior to those possessed by any other nation on earth.” Ugly American Exceptionalism!

I read Kaplan for a reminder as to why do insertions. Walt: “In my visits to the hospitals, I found it was in the simple matter of Personal Presence, and emanating ordinary cheer and magnetism, that I succeeded and help’d more than by medical nursing or delicacies, or gifts of money, or anything else.”