The moral compass of Les Misérables thus spreads far beyond the history, geography, politics and economics of the world in which its story is set. The novel achieves the extraordinary feat of being at the same time an intricately realistic portrait of a specific place and time, a dramatic page-turner with masterful moments of theatrical suspense and surprise, an encyclopedia of facts and ideas and an easily understood demonstration of generous moral principles that we could do far worse than apply to our own lives.

–David Bellos, The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventure of Les Miserables, 259

But Cosette and Valjean each become the other’s fulfillment, the missing piece in their life puzzles. “In that mysterious moment when their hands touched,” writes Hugo, “they were welded together. When their two souls saw each other, they recognized mutual need, and they embraced. The bishop has brought one thing to Valjean’s life; now Cosette has brought another. “The bishop,” writes Hugo, “had caused the dawn of virtue on his horizon; Cosette invoked the dawn of love.”

–Bob Welch, 52 Little Lessons from Les Misérables, 75

Jean Valjean felt the pavement slipping away under him. He entered into this slime. It was water on the surface, mire at the bottom. He must surely pass through. To retrace his steps was impossible. Marius was expiring, and Jean Valjean exhausted. Where else could he go? Jean Valjean advanced. Moreover, the quagmire appeared not very deep for a few steps. But in proportion as he advanced, his feet sank in. He very soon had the mire half-knee deep and water above his knees. He walked on, holding Marius with both arms as high above the water as he could. The mud now came up to his knees, and the water to his waist. He could no longer turn back. He sank in deeper and deeper. This mire, dense enough for one man’s weight, evidently could not bear two. Marius and Jean Valjean would have had a chance of escape separately. Jean Valjean continued to advance, supporting this dying man, who was perhaps a corpse.

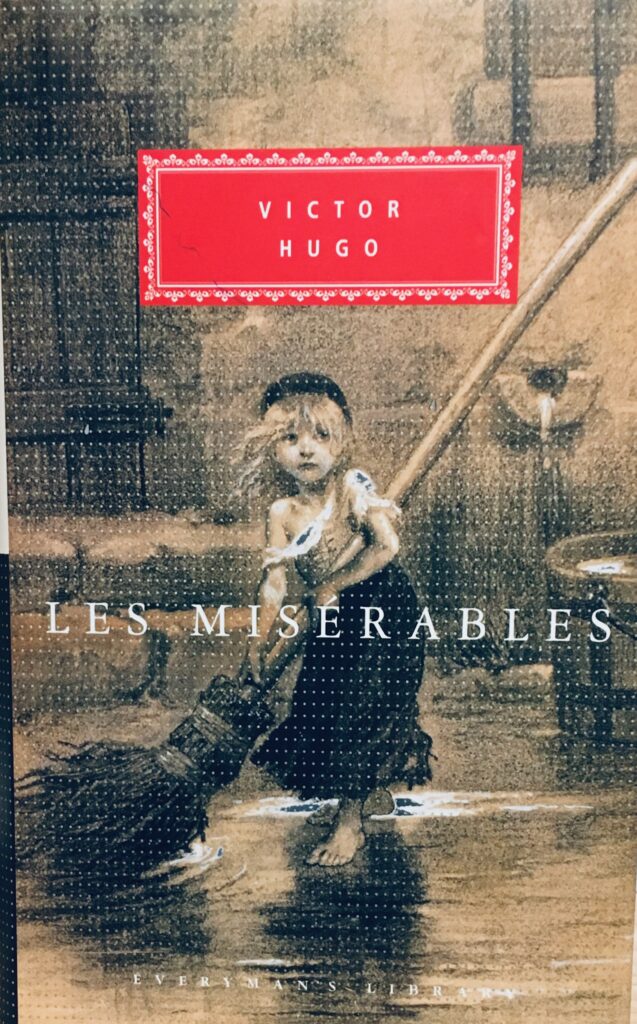

–Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, Everyman’s Library, translated by Charles E. Wilbour, 1273

Title above is #6 of Why Read the Classics? by Italo Calvino

Two years ago, thirteen of us were meeting every two weeks (by Zoom) and making our way through Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I wonder if there are any friends interested in reading Hugo’s novel over the course of a year…