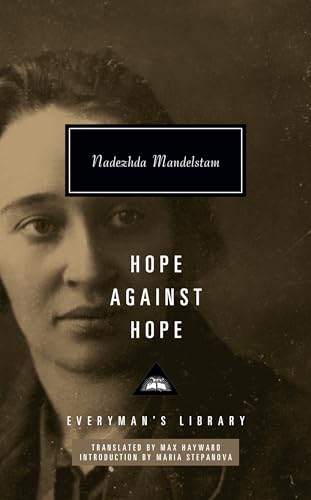

I am engrossed these days rereading Nadezhda Mandelstam’s inspiring memoir, Hope Against Hope.

It’s an account of her life with her husband, the acclaimed poet Osip Mandelstam who ran afoul of the revolutionaries of the Soviet Union. His most serious crime: writing a poem critical of Stalin.

During this morning’s reading of the chapter, “A Piece of Chocolate,” I was reminded of a Dostoevskyan theme the by scholar Gary Saul Morson:

We traveled in crowded cars and on river steamers, we sat in busy stations swarming with people, but nowhere did anybody pay any attention to the outlandish spectacle of two people, a man and a woman, guarded by three armed soldiers. Nobody gave us so much as a backward glance. Were they just used to sights like this in the Ural, or were they afraid of getting infected? Who knows? Most probably it was a case of the peculiar Soviet etiquette that has been carefully observed for several decades now: if the authorities are sending someone into exile, all well and good, it’s none of our business. The indifference of the people around us hurt and upset M. “They used to give alms to convicts and now they don’t even look at them.” With horror he whispered in my ear that in front of a crowd like this they could do anything to a prisoner—shoot him down, kill him, torture him—and nobody would interfere. Bystanders would just turn their backs, not to be upset by the sight. During the whole journey I tried to catch somebody’s eye, but never once succeeded.

Perhaps only the Ural was so stony-faced? In 1938 I lived in Strunino, in the permitted zone a hundred kilometers from Moscow. This was a small textile town on the Yaroslavl railroad and in those years trainloads of prisoners passed through it every night. People coming in to see my landlady spoke of nothing else. They were outraged at being forbidden to give the prisoners bread. Once my landlady managed to throw a piece of chocolate through the bars of a broken window in one of the prison cars—in a poor working-class family, chocolate was a rare treat and she had been taking it home for her little daughter. A soldier had sworn at her and swung the butt of his rifle at her, but she was happy for the rest of the day because she had managed to do at least this much. True, some of her neighbors sighed and said: “Better not get mixed up with them. They’ll plague the life out of you. They’ll have you up in front of the factory committee.” But my landlady didn’t go out to work, so she wasn’t afraid of any factory committee.

Will anybody in a future generation ever understand what that piece of chocolate with a child’s picture on the wrapper must have meant in a stifling prison train in 1938? People for whom time had stopped and space had become a prison ward, or a punishment cell where you could only stand, or a cattle truck filled to bursting with its freight of half-dead human beings, forgotten outcasts who had been struck from the rolls of the living, stripped of their names, numbered and registered before being shipped to the black limbo of the prison camps—it was such as these who now suddenly received or the first time in many months their first message from the forbidden world outside: a little piece of chocolate to tell them that they were not yet forgotten, and that people were still alive beyond their prison bars.