for Matt Miller

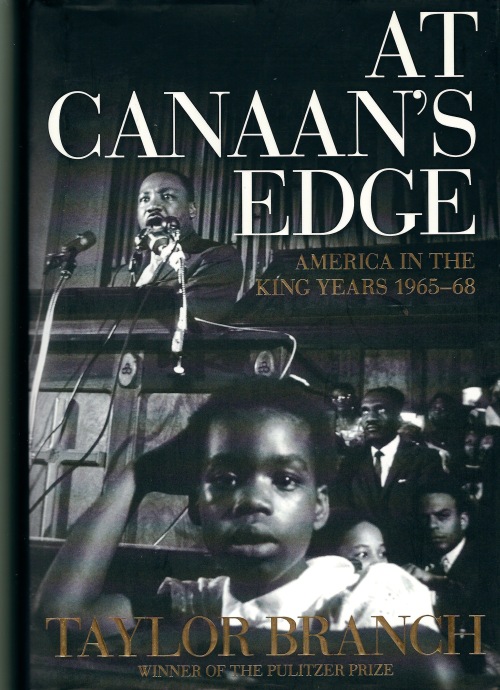

Taylor Branch, At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-1968

Simon and Schuster, 2006

The following are passages from this third volume of a gripping, recent history of the US.

America’s Founders centered political responsibility in the citizens themselves, but, nearly two centuries later, no one expected a largely invisible and dependent racial minority to ignite protests of steadfast courage—boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, jail marches—dramatized by stunning forbearance and equilibrium into the jaws of hatred. xi

Marchers stand here on the brink of violent suppression in their first attempt to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, after which thousands of ordinary Americans will answer King’s overnight call for a nonviolent pilgrimage to Selma. Three of them will be murdered, but the quest to march beyond Pettus Bridge will release waves of political energy from the nucleus of human freedom. The movement will transform national politics to win the vote. Selma will engage the world’s conscience, strain the embattled civil rights coalition, and embroil King in negotiations with all three branches of the United States government. It will revive the visionary pragmatism of the American Revolution. xiii

MLK: “Well, I’m gonna put out a call for help.” 57

MLK: “I say to you this afternoon that I would rather die on the highways of Alabama than make a butchery of my conscience…. If you can’t accept blows without retaliating, don’t get in the line.” 74-75

Mother Pollard: “My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.” 107

Hosea Williams: “I’m not interested in criticizing Sheriff Clark, I’m interested in converting Sheriff Clark!” 123

Andrew Young: “This is a revolution, a revolution that won’t fire a shot….We have come to love the hell out of the State of Alabama.” 163

MLK: “How long? Not long!” 170

Jonathan Daniels: “We are trying to live the Gospel.” 210

Andrew Young: “But if we are true to Gandhi, and seek to attack issues rather than people, we can hope to inspire even our opposition to new moral heights, and thereby overcome.” 284

MLK: “I’m here [in Los Angeles] because at bottom we are brothers and sisters. We all go up together or we go down together. We are not free in the South, and you are not free in the cities of the North.” 297

Above any political ideology, [Malcom X] clung to the belief that only one force could dissolve racial hatred at the root—purified, nonsectarian Islam—but the Autobiography minimized this notion because ghostwriter Alex Haley and the Grove Press editors knew it would leave Americans cold. 374

King summoned the bold protest of ancient sources—“Today we particularly need the Hebrew prophets”—whose words had goaded the movement past fear and silence. “They did not believe that conscience is a still, small voice,” he said. “They believed that conscience thunders, or it does not speak at all.” He quoted Amos on justice, Micah on beating swords into plowshares, and Isaiah on what King called an “inescapable obligation” to renounce violence of spirit: “Yea, when you make many prayers/I will not hear/Your hands are full of blood/Wash you, make you clean/Put away the evil off your doings from before mine eyes.” 394

MLK: “We are not newcomers here. We do not have to give our credentials of loyalty. For you see, we worked here and labored for two centuries without wages.” 412

Senator Richard Russell: “we killed civilians in World War II and nobody opposed. I’d rather kill them [the Vietnamese] than have American boys die.” 425

In the Grand Ballroom, Freedom Rider James Peck leapt to his feet among the black-tie guests just as Johnson began his acceptance speech, shouting,”Peace in Vietnam! Peace in Vietnam” only twice before a hand clapped over his mouth and agents dragged him off to serve sixty days. 448

An old farmer: “We been walkin’ with dropped down heads, a scrunched up heart, and a timid body in the bushes, but we ain’t scared anymore!” 462

MLK: “I’m tired of shouting. I’m tired of hatred. I’m tired of selfishness. I’m tired of evil. I’m not going to use violence no matter who says it!” 489

[To Stanley Levison, one of King’s principal lawyers] the cry of black power disguised a lack of broad support for SNCC and CORE, with cultural fireworks that amounted to an extravagant death rattle. MLK: “They’re just going to die of attrition and as they die they’re going to be noisier and more militant in their expression …. Because they’re weak, they’re making a lot of noise, and we don’t want to fall into that trap.” 494

In Chicago: MLK: “I have never in my life seen such hate. Not in Mississippi or Alabama. This is a terrible thing.” 511

Jesse Jackson: “I’m going to Cicero!” 515

MLK: “Violence as a strategy for social change in America is nonexistent.” 539

A. D. King on a possible protest at the Kentucky Derby: “We can start by planning to disrupt the horses, since white folks think more of horses than of Negroes.” 589

MLK: “There’s something strangely inconsistent about a nation and a press that will praise you when you say, ‘Be non-violent toward Jim Clark,’ but will curse and damn you when you say, ‘Be non-violent toward little brown Vietnamese children.’” 604

MLK: “What I am trying to get you to see this morning is that a man may be self-centered in his self-denial and self-righteous in his self-sacrifice. His generosity may feed his ego and his piety may feed his pride. So, without love, benevolence becomes egotism and martyrdom becomes spiritual pride.” 636

MLK: “I said some time ago—and the press jumped on me about it, but I want to say it today one more time, and I am sad to say it—we live in a nation that is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” 689

The Kerner Commission: “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negroes can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it…. White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.” 705

King said [Andrew]Young had given in to doubt, [James] Bevel to brains, and [Jesse] Jackson to ambition. He said they had forgotten the simple truths of witness. He said the movement had made them, and now they were using the movement to promote themselves. 743

MLK: “And some began to say the threats—or talk about the threats— that were out, what would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers. Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop.” 758

His oratory mined twin doctrines of equal souls and equal votes in the common ground of nonviolence, and justice refined history until its fires dimmed for a time….King himself upheld nonviolence until he was nearly alone among colleagues weary of sacrifice. To the end, he resisted incitements to violence, cynicism, and tribal retreat. He grasped freedom seen and unseen, rooted in ecumenical faith, sustaining patriotism to brighten the heritage of his country for all people. These treasures abide with lasting promise from America in the King years. 771