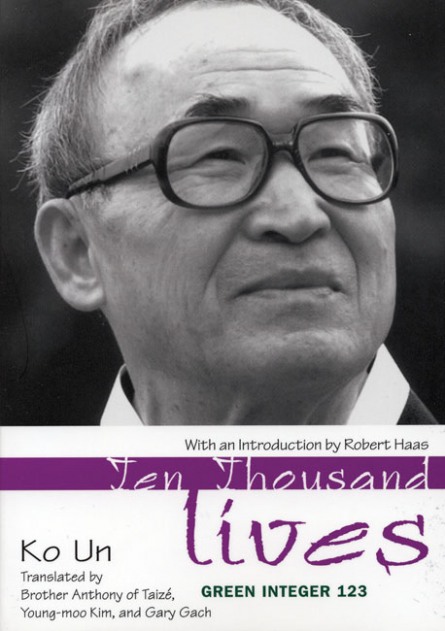

1.

Ko Un‘s Ten Thousand Lives is a remarkable sample in English of his twenty-volume work in Korean, known as Maninbo. In his early years, he was a Buddhist monk. Later, he was part of the pro-democracy movement in South Korea and ended up in jail. The following is from the introduction by the translators Brother Anthony, Kim Young-Moo and Gary Gach: “In that dark prison, in such a dark time, Ko Un’s Buddhist training helped sustain him. And he reflected deeply on the significance of his vocation as poet, its connection with Korean history. In so doing, he felt a deep connection between his own suffering and those of the many Koreans he’d encountered in his life, either directly or in the pages of books. He felt called to promise them that, if ever he came out alive, he would set about writing a poetic record of the life of every person he’d ever known or known of. He found he could let events take their course; even if he was destined to die, the very fact of having made this vow was enough.”

2.

Han Ha-un

When the 1940s were nearly done

and I was in second year of middle school,

I was making the two-mile journey home

along a dusky path at twilight

trudging along

getting near the Mijei crossroads

when suddenly I noticed something lying

in the middle of the dark path.

My heart skipped a beat

then fluttered wildly as I picked it up.

It was a book.

A poetry book.

The poems of Han Ha-un, Korea’s leper-poet.

‘On and on along the earthen path….’

Once back home,

I read and reread it all night long.

I read the commentary too, written by a certain Cho Yŏng-am,

three or four times,

and the commentary by someone called Ch’oi Yŏng-hae, too.

From that day on, I was Han Ha-un.

From that day on, I was a wandering leper.

From that day on, all the world was an earthen path.

From that day on, I was a poet – a sorrowful poet.

—Ten Thousand Lives

3.

Cho Bong-am

One day in January 1958

Cho Bong-am, chairman of the Progessive Party,

Stood at the foot of the scaffold in Sŏdaemun Prison.

His last words were:

“Give me a cigarette.”

Having been refused even one last cigarette,

Thud! His two feet hung dangling.

Here, since his death,

Faithful to his hope

At least in words,

“unification” no longer means invading the North,

As Syngman Rhee insisted,

And saying “peaceful reunification” is no longer a crime.

But the day is still far away

When the shadow of his death will lift.

When his comrades went to jail

Or came back out again,

That fine fellow

Would donate a sack of rice

Or a cartload of coal

And so give courage to that comrade’s wife. A fine fellow, indeed.

Last night in a dream I saw Cho Bong-am, smoking a cigarette.

—Ten Thousand Lives

4.

I did not come to this world to play.

As birds sing, I came to this world to sing,

Keep silent, and to work.

—Ko un, What? 108 Zen Poems.

This so disturbs me Mark…I know that need to devour…that all consuming desire to become the poem I am reading. I can see the path, the dust, the lengthening shadows…and then the book! battered, crumpled, abandoned…and the pull, the longing, the magnetic force drawing me in.

Mark, sometimes the pull of something needing to be written, needing to escape my mind, it is maddening until I surrender. It is like I am just a vessel, a carrier, a servant to the word.

Thanks for disturbing me