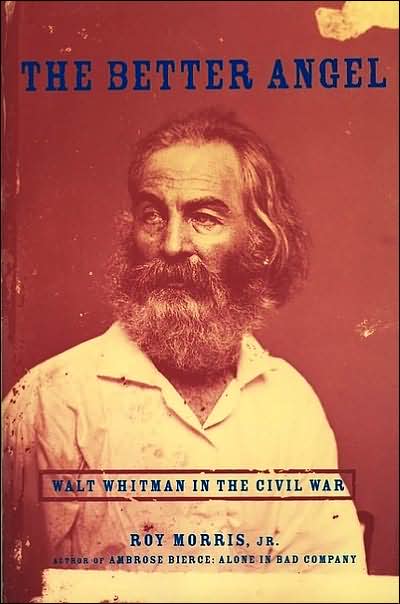

Roy Morris, Jr., The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War

This book tells the story of Walt’s practice of the 4th Tiep Hien precept, not to look away from suffering. Actually, here’s the original precept: “Do not avoid contact with suffering or close your eyes before suffering. Do not lose awareness of the existence of suffering in the life of the world. Find ways to be with those who are suffering, including personal contact, visits, images and sounds. By such means, awaken yourself and others to the reality of suffering in the world.”

The book begins with Walt in NYC: he lost his job as editor of Brooklyn Eagle, weathered a mixed reception of last book, dealt with family woes, learned that his publishers had gone bankrupt, and endured the end of unhappy love affair. Oy! But it was the reality of suffering that got him out of his rut of bohemian posturing and late-night cruising. On to Washington!

There, Walt roamed the hospitals that held the wounded and the maimed from the Civil War. In this sense, then, he had to complement the Via Positiva he walked—the buoyant, cheerful, exuberant self that gave birth to the first edition of Leaves of Grass and which I loved reading in Texas this summer—and he learned to walk the Via Negativa, into that dark night of the nation’s soul, manifested in the devastation of the war experience.

I say this to my students, in pieces like “Accompaniment in Palestine,” it’s not all about you giving, it’s both/and: So, Whitman said, “People used to say to me, Walt you are doing miracles for those fellows in the hospitals. I wasn’t. I was doing miracles for myself.” [100] How compelling can cruising be when you’ve seen suffering like that: “Nothing in his far from sheltered life had prepared him for the sights, sounds, and the smells of the army hospitals—they were literally a world unto themselves.” [88]

And so, like Kathy Kelly 140 years later, we see Whitman performing the “works of mercy” as a counter to the works of war. He found ways to be with the soldiers, gave them treats, wrote letters for them, sat in silence, touched them, did not preach at them, and loved them. Morris: “From December 1862 until well after the war was over, he personally visited tens of thousands of hurt, lonely, and scared young men in the hospitals in and around Washington, bringing them the ineffable but not inconsiderable gift of his magnetic, consoling presence. In the process, he lost forever his own good health, beginning a long decline that would leave him increasingly enfeebled for the rest of his life.” [5]

I can see why Laura Bush initially thought of Whitman for her poetry program; he was pro-Civil War, pro-Union. But his experience showed him another side, which he communicated to his mother: “One’s heart grows sick of war, after all, when you see what it really is; every once in a while I feel so horrified and disgusted—it seems to me like a great slaughter-house and the men mutually butchering each other.” [143]

The years in DC took its toll on Whitman, such that he was probably suffering from akin to secondhand PTSD. His testimony: “It is lucky I like Washington in many respects, and that things are upon the whole pleasant personally, for every day of my life I see enough to make one’s heart ache with sympathy and anguish here in the hospitals, and I do not know as I could stand it if it was not counterbalanced outside. It is curious, when I am present at the most appalling things—death, operations, sickening wounds (perhaps full of maggots)—I do not fail, although my sympathies are very much excited, but keep singularly cool; but often hours afterwards, perhaps when I am home or out walking alone, I feel sick and actually tremble when I recall the thing and have it in my mind again before me.” [143-144] And God only knows what my student who was in Iraq is going through these days, still. Will he be going back for another tour?

Shout out to Walt that he was religionless. “[Unlike the preachers]. He gave no lectures, handed out no tracts, and prayed no prayers for the immortal souls of white-faced boys writhing on their beds. Instead, he simply sat and listened. That was what they needed most, more than any medicine, and Whitman sensed it instinctively. ‘I supply often to some of these dear suffering boys in my presence & magnetism that which doctors nor medicines nor skills no any routine assistance can give,’ he wrote. ‘I can testify that friendship has literally cured a fever, and the medicine of daily affection, a bad wound.’” [6] One man said, “Walt Whitman didn’t bring any tracts or Bibles; he didn’t ask you if you loved the Lord, and didn’t seem to care whether you did or did not.” [109]

One implication of the 4th precept is that it gives us a comparative frame of reference: “Now that I have lived for eight or nine days amid such scenes as the camps furnish and realize the way that hundreds of thousands of good men are now living, and have had to live for a year or more, not only without any of the comforts, but with death and sickness and hard marching and hard fighting, (and no success at that,) for their continual experience—really nothing we call trouble seems worth talking about.” [75]

So even here in St. Louis, be prepared to listen, let go, take risks, extend myself, go further, celebrate the small moments of exuberant intimacy, and write it all down.

— 5 October 2005