Pedro Casaldáliga & José-Maria Vigil, Political Holiness: A Spirituality of Liberation

Those who struggle for utopia, for radical change, saints marked by the liberating spirit, are all of a piece; they carry faithfulness from the root of their being on to the smallest details that others overlook: attention to the littlest, respect for subordinates, eradication of egoism and pride, care for common property, generous dedication to voluntary work, honesty in dealings with the state, punctuality in correspondence, not being impressed by rank, being impervious to bribes….Detailed everyday faithfulness is the best guarantee of our utopias. The more utopic we are, the more down-to-earth! (p. 58)

March 24, 1995 marks the 15th anniversary of the assassination of Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero. Two weeks before he was murdered while celebrating liturgy, Romero acknowledged the likelihood of a violent death but he was convinced, “I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.” Now widely cherished as a saint by the poor throughout Latin America, Romero indeed proved to be an inspiration to innumerable unknown Christians as well as a few famous ones — such as the Salvadoran Jesuit intellectuals — who suffered the same fate of persecution and martyrdom for their work on behalf of a new society. [1]

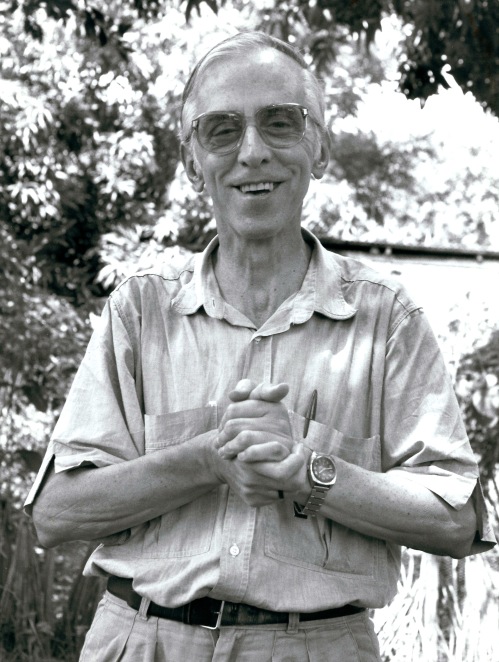

Political Holiness is an up-to-date examination of the spirituality that defined Romero and the continental cloud of witnesses that continues to defy institutionalized injustice with Christian hope. [2] The authors are well qualified to share the fruits of their reflections on their experience: Vigil has long labored as a theologian in Nicaragua, while Brazilian Dom Pedro has been one of the most courageous of Latin American bishops and, like Romero, he has been perennially threatened with death because he has championed the rights of the poor over the privileges of rich landowners. This book is a deceptively simple and quite compelling manual and guide to the dominant fundamentals, themes, and issues of the spirituality that has emerged in full force in the last several decades in the southern hemisphere. For specialists and students in spirituality, it is bound to provoke deeper reflection on spirituality, and Christian spirituality.

In their introduction, “Spirit and Spirituality,” the authors clarify the meanings of their central terms. They define “spirit” or “spirituality” for a person or community as “their life motivation, their disposition, what inspires their actions, their utopia, their causes, regardless of whether these are better or worse, good or evil, in accordance with our own or not” (Political Holiness, 4-5). As such, spirituality is an essential dimension of human life, whether one is a member of the Christian Coalition or the Catholic Worker. The authors then distinguish two kinds of spirituality. The first is an “ethical-political spirituality that exists in all of us, whether we know the Christian revelation or not” (14). The second is the “religious, evangelical-ecclesial spirituality” deriving from explicit Christian categories of understanding salvation. This approach to spirituality guards against any Christian spiritual triumphalism which treats non-Christians as devoid of spirituality (14).

This approach determines the two-fold structure of the book. First, they probe the basic spiritual themes in the “Spirit of Liberation” in Latin America. This spirituality can be discerned in all those who struggle for the liberation of the continent’s poor and oppressed, even if they are explicit atheists. Second, they interpret such themes from the particular standpoint of “The Liberating Spirit of Jesus Christ.” Thus, the specific Christian spirituality is the basic option of following of Jesus, of claiming his cause as one’s own, of seeking the utopia for he lived and died in the conflictual social-political world of Latin America.

In Part One the authors describe several pertinent themes and characteristics of the “spirit of liberation” in Latin America. At the core of this spirituality is a passion for reality. A commitment to critical realism demands that social science and analysis aid the people in understanding the historical and structural causes of the poverty and oppression. Linked to this passion is an abiding sense of ethical indignation which revolts against the countless violations suffered by people, which perceives an ineluctable demand to respond to this social sin, and which makes a basic option and commitment to the poor [3]: How different is this spirituality from an “inward-looking religious feeling, which makes no reference to this ‘major world situation’ [of massive poverty], that of certain charismatics, of spiritists, and others” (26). And yet this steady indignation does not exclude the people’s abiding sense of joy, festival, hospitality, and openness.

Moreover, this spirit of liberation finds expression in a profound solidarity which is a “legacy sealed with the blood of thousands of brothers and sisters” (48), and which binds the struggles of the entire continent together — from Haiti to Chile — in the quest for liberation. And lest the spirituality of liberation depicted here be seen as exclusively attentive to the great struggles of history, the authors propose the centrality of an “everyday faithfulness,” which is manifested in such small details as the authors’ following list: “respect for subordinates, eradication of egoism and pride, care for common property, generous dedication to voluntary work, honesty in dealings with the state, punctuality in correspondence, not being impressed by rank, being impervious to bribes” (58).

In Part Two, the distinctive Christian embodiment out of this spirit of liberation is based on recovering the spirit and dream of the historical Jesus. In the Latin American context, this Jesus is seen as poor, subversive, ecumenical, feminist, persecuted, and martyred (96-100). The authors emphasize that Jesus’s basic option and obsession was for the Reign of God. They then identify the “criterion for measuring the Christian identity of persons, values, or any other reality, is their relationship to the reign of God, their relationship to Jesus’ cause” (81): Simply put, that cause of transfiguring the present realm in accord with God’s justice and peace, a reign of brotherhood and sisterhood.

In this often perilous context of staking one’s life on the primacy of the Reign, the authors indicate a major struggle in Latin America. Unlike Europe, the struggle is not one of maintaining belief, as in whether or not God exists, but of claiming allegiance, as in which God one serves: The Christian God revealed by Jesus or such contemporary idols as money, power, and national security. The interrelationship of the historical Jesus and the Reign-focus is illumined by the authors’ option for a macro-ecumenism. This is a phenomenon on the continent that recognizes a communion beyond a dialogue among Christians to include all those who work for the coming of the Reign. The authors explain, “Whenever men or women, in whatever circumstance or situation, under whatever banner, work for the causes of the Reign (love, justice, fraternity, freedom, life), they are fighting for the causes of Jesus, they are fulfilling the purpose of their lives, they are doing God’s will. In contrast, those who call themselves Christians and live and fight for their churches are not always doing God’s will. The final criterion by which God will judge human beings (Matt. 25:31-45) is just this: totally ecumenical, non-ecclesiastical, non-confessional, not even religious, wider than any race, culture or church” (167-8). [4]

One wonders if there will be a forthcoming instruction from the Vatican on certain aspects of such macro-ecumenism. The authors go one to treat the Trinity, Mary, the Incarnation, and penance, among many other topics, all from the perspective of making an option to struggle with the poor.

In a separate chapter the authors sum up the nature of Christian political holiness which is a dramatic departure from previous ideals of holiness, supposedly detached from society or political conflict (178). This political holiness constitutes a new form of asceticism, rooted in an option for the poor. This holiness expresses ethical and political virtues in the broad struggle for human rights. This contrasts with certain spiritualities that lack a passion for social reality or ethical indignation; for example, the North American spiritual supermarket abounds in techniques and regalia for relatively privileged people to pursue individualistic spiritual quests.

A great value of this work is that it stimulates the reader to make connections with the equivalents of other spiritualities of political holiness. One is the engaged Buddhist movement of Vietnam which was born during the 1960s in the crucible of religious repression and then a full-scale U.S. military invasion. Perhaps the most acclaimed exponent of engaged Buddhism, Thich Nhat Hanh, has been able to reach many ex-Christian and Jewish North Americans because of his non-dogmatic emphasis on a daily contemplative practice. [5] Casaldáliga and Vigil also deem the practice of “contemplation in liberation” to be critical to Latin American spirituality, going so far as to assert, “A pastoral worker who does not give at least half an hour a day to individual prayer, in addition to what takes place in the team, does not measure up to the standard required of a pastoral worker” (122).

Also, Michael Lerner’s recent work, Jewish Renewal, has many similarities to Political Holiness, in its own recovery of the revolutionary message of Judaism and its emphasis on the God that makes possible healing and transformation. [6] A vibrant common thread running through these macro-ecumenical approaches is precisely the praxis of social virtues — such as civic courage and solidarity — that often bring its practitioners in conflict with established church and state. In our days, “political holiness” is simply another expression for the virtue of dissidents, as the authors are quick to claim, outside and inside the church.

Over the years, Latin American liberation theology has been criticized variously for an uncritical glorification of “the people,” an indifference to cultural differences, especially indigenous forms of religiosity, and an allegedly dangerous marriage with Marxism. Apropos to the first, the authors warn against the tendencies of both “vanguardism” and “basism,” the latter being the assumption that “the people’s” opinions are somehow beyond reproach (40). Regarding cultural differences, the authors respect and esteem indigenous practices as well as confront the institutional church’s complicity in the European conquest of the Americas. As to the issue of Marxist “contamination,” undoubtedly, the authors of this work see capitalism as a nefarious idol, and they frequently speak of “utopia.” And yet, their denunciation and annunciation comes form a profound Christian spiritual base, characteristic of the “seven marks of the new people:” A critical clarity, contemplation on the march, the freedom of the poor, fraternal solidarity, the cross of conflict, the gospel insurrection, and the stubborn Easter hope (200-202). Far more than any Marxist ideology, this biblically-based and persecuted spirituality may alternately inspire North Americans — for its profound commitment — or make us squirm in our seats — for our lack of comparable passion and indignation before our national reality.

Political Holiness is a powerful outline of the spiritual emphases of a church of martyrdom with which North Americans must reckon: The powers and principalities arising out of the North show no signs of changing their priorities to accord with the commitment to the “logic of the majority” which is at the root of this distinctly Latin American spirituality. The global U.S. arms trade, NAFTA, and the U.S. efforts to dictate the course of events in Haiti all reveal that oppression and a correlative liberation spirituality have not evaporated. The political and economic fates of the North and South have long been inextricably entwined, and as this book makes so clear, so our spiritual destinies are bound together. The pressing issue for North American Christians to decide is whether that spiritual association is based on indifference, complicity with power, or a solidarity with those who “take up the conflictive identity of this continent of ‘captivity and liberation’ as their deepest personal and historical challenge, and as their most human and Christian utopia” (xxviii). In other words, that the people of Latin America also have life and have it abundantly (John 10: 10).

–Spring 1995

Notes

[1] Quoted in Pedro Casaldáliga & Jose-María Vigil, Political Holiness: A Spirituality of Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994), 53.

[2] See earlier studies published in English, for example, Salvadoran Jon Sobrino’s similarly entitled work, The Spirituality of Liberation: Toward Political Holiness (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1988) and Gustavo Gutierrez, We Drink From Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1984).

[3] I think here of the steadfast commitment of U.S. linguist and activist (and atheist) Noam Chomsky to the struggles of liberation, including Central America, Palestine, and East Timor. Chomsky’s recent work, Year 501: The Conquest Continues (Boston: South End Press, 1993), reflects the passion for reality, ethical indignation, and solidarity so esteemed by the authors.

[4] Incidentally, this “macro-ecumenism” was identified by Trappist Thomas Merton in 1966 in a letter he wrote on behalf of the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh: “[Thich Nhat Hanh] is more my brother than many who are nearer me by race and nationality, because he and I see things exactly the same way…. I have far more in common with Nhat Hanh than I have with many Americans, and I do not hesitate to say it. It is vitally important that such bonds be admitted. They are the bonds of a new solidarity and a new brotherhood [sic] which is beginning to be evident on all five continents and which cuts across all political, religious and cultural lines to unite young men and women in every country in something that is more concrete than an ideal and more alive than a program. The unity of the young is the only hope for the world.” Thomas Merton, “Nhat Hanh is My Brother” in The Nonviolent Alternative, ed. Gordon C. Zahn (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1980), 263-4.

[5] An excellent introduction is Thich Nhat Hanh, Interbeing: Fourteen Guidelines for Engaged Buddhism (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1993, rev. ed.).

[6] Michael Lerner, Jewish Renewal: A Path of Healing and Transformation (New York: Putnam/Grosset, 1994). This work could be instructive to both Casaldáliga and Vigil as an example of a prophetic and dynamic contemporary Judaism, as there are hardly any references in their book to Jews or Judaism as a continuing and vital tradition after the time of Jesus. Though the suffering of Jews at the hands of Christians was in Europe, and not in Latin America, it is nevertheless important to recognize that, vis-à-vis Jews, the Christian theological tradition exercised the opposite of a preferential option for the poor: defamation and marginalization of Jews were the norm, until quite recently.

“Political Holiness” gives language and clarity to my biggest problem with the current culture of Christianity. I feel as though I have a sense of shared understanding of the dangers of political unholiness. Moreover, this book offers a much needed answer to anyone who finds themselves entangled in the mess of the individualistic focused, superiority driven, void of societal reality, costume of religiosity called Northern Christianity. Thank you for this; I need more!