1.

At one-hour intervals the night guards paced past every room. Each time I heard the approaching footsteps, I jumped into bed and feigned sleep. And as soon as the guard passed, I got back out of bed onto the floor area of that light-glow, where I would read for another fifty-eight minutes—until the guard approached again. That went on until three or four every morning. Three or four hours of sleep a night was enough for me. Often in the years in the streets I had slept less than that…

Book after book showed me how the white man had brought upon the world’s black, brown, red, and yellow peoples every variety of the sufferings of exploitation. I saw how since the sixteenth century, the so-called “Christian trader” white man began to ply the seas in his lust for Asian and African empires, and plunder, and power. I read, I saw, how the white man never has gone among the non-white peoples bearing the Cross in the true manner and spirit of Christ’s teachings—meek, humble, and Christlike…

I have often reflected upon the new vistas that reading opened to me. I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life. As I see it today, the ability to read awoke inside me some long dormant craving to be mentally alive. I certainly wasn’t seeking any degree, the way a college confers a status symbol upon its students. My homemade education gave me, with every additional book that I read, a little bit more sensitivity to the deafness, dumbness, and blindness that was afflicting the black race in America. Not long ago, an English writer telephoned me from London, asking questions. One was, “What’s your alma mater?” I told him, “Books.” You will never catch me with a free fifteen minutes in which I’m not studying something I feel might be able to help the black man.

—The Autobiography of Malcom X

2.

I read [Balzac] especially during the years I was in prison [1953-1955]. I’m almost nostalgic for those years in prison, because that’s the time in my life when I had the most time to read. I read constantly, fifteen hours a day. Although it was mostly political essays, history books, a lot of Martí—but all sorts of literature and novels, too. That, for me, was a real cultural university. A ‘fertile prison,’, as one historian has put it.

There, I remember reading several Balzac novels, such as Père Goriot, Eugénie Grandet, and Le Colonel Chabert, his very famous series La Comédie humaine. Before that, I’d already read La Peau du chagrin [The Wild-Ass’s or Onager’s Skin], a fascinating story of a man who becomes involved in a diabolical pact with a strange animal skin that grants him three wishes but, at the same time, shrinks.

According to some scholars, Karl Marx liked Balzac’s realistic style. He admired Balzac immensely, as he also admired—one should emphasize—Cervantes and Quixote. Apparently Marx intended to write a critical study on La Comédie humaine after he finished his works on economic and politics. In The Communist Manifesto one can see the influence of Balzac’s style—the clarity of the prose, the effectiveness and elegance of the simple expression. Balzac wrote his novels serially for popular newspapers with large readerships; he knew how to write for large audiences, for the masses. Had it not been for Balzac, the Manifesto might not have had the success it had, the enormous readership. A paradox, eh? Because Balzac was not Marxist at all, and although he was one of the first novelists critical of the bourgeoisie that was beginning to become so powerful in society, down deep he was a monarchist.

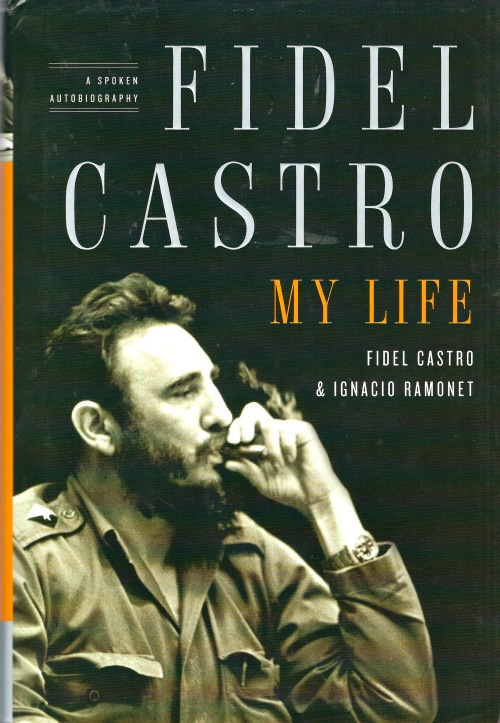

—Fidel Castro, My Life: A Spoken Autobiography