In this book I portray the Russian tradition as a dialogue of the dead (and a few still living) extending over centuries. Novelists and their characters, critics and ideologists, argue about ultimate questions that obsessed Russians and concern humanity everywhere and always.

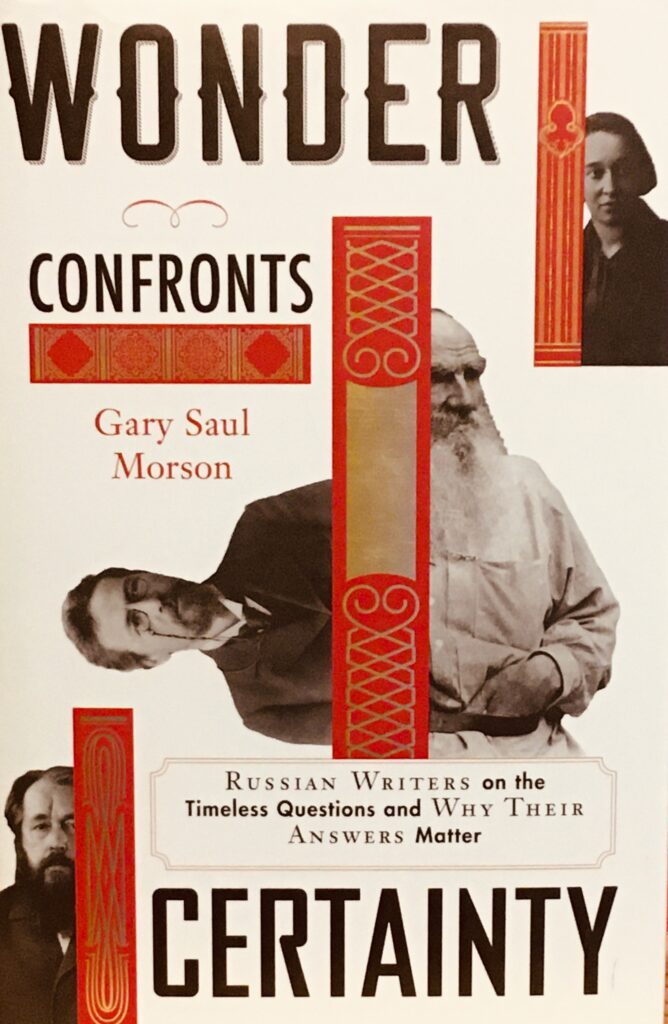

—Gary Saul Morson, Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter

My first thought was: how will I ever find words for this? What sustained my hope? Witnesses. Only the words of witness were equal to what I saw and what I wanted to write about. Today, I see the witness as the main protagonist in literature. People say to me: “Well, you know, memories, recollections—that’s not history and not literature either. It’s just life, rubbish that the artist hasn’t polished. It’s the raw material of conversation, just chitchat.” But I see things differently. It is there, in the live human voice, in the live reflection of reality, that the mystery of our presence is hidden, and the insurmountable tragedy of life is laid bare. Life’s chaos and passion. Its singularity and inscrutability. Shouts and sobs can’t be polished, or the main thing will be neither the tears nor shouts, but the polish.

—Svetlana Alexievich, In Search of the Free Individual: The History of the Russian-Soviet Soul

When you think of Russian literature, do you have in mind Tolstoy or Chernyshevsky, Dostoevsky or Gorky, Chekhov or Lenin? One can already discern the divergence of the two traditions in the first years of Alexander II’s reign.

—Gary Saul Morson, Wonder Confronts Certainty

He opened his eyes and looked at his son. He felt sorry for him. His wife came over to him. He looked at her. She was gazing at him with a despairing expression, openmouthed, and with undried tears on her nose and cheek. He felt sorry for her…. He was sorry for them, he had to act so that it was not painful for them. To deliver them and deliver himself from these sufferings. “How good and how simple,” he thought. “What’s become of it? Where are you, pain?” He became attentive.

–Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Trotsky insisted that Bolsheviks must “put an end once and for all of the papist-Quaker babble about the sanctity of human life” and in a telegram to comrades in Astrakhan instructed: “Execute mercilessly.”

—Gary Saul Morson, Wonder Confronts Certainty

This was why we had outlawed the question “What was he arrested for?” “What for?” Akhmatova would cry indignantly whenever, infected by the prevailing climate, anyone of our circle asked this question. “What do you mean, what for? It’s time you understood that people are arrested for nothing!”

—Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope against Hope

The same ideals and feelings that had led Alyosha to Zosima might have led him to atheism and socialism since both offer divergent paths tending toward the same goal of the transformation of earthly life into a society closer to the Kingdom of God, but the first would be guided by Christ, while the second is deprived of the moral compass that He provides.

—Joseph Frank, Dostoevsky: The Mantle of the Prophet