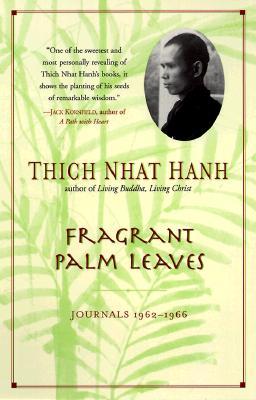

Thich Nhat Hanh, Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals 1962-1966*

We must strengthen ourselves for the coming test.

–Thich Nhat Hanh [p. 66]

This book is an enchanting glimpse into the Vietnamese Zen Master long before he became well known in the United States. Entries come from when he was in his mid-thirties at Princeton and Columbia, and thereafter back in Vietnam as the war heated up.

It’s eerie reading the parts in USA journals when he is recalling the serenity and delights of a bucolic existence in the later 1950s, all of which would soon drastically change with the U.S. military escalation. Sometimes he stays up late writing. He confronts his loneliness. He fondly remembers home: “Vietnam doesn’t have snow, but it does have beautiful scenes that Princeton doesn’t, like coconut trees reflecting in rivers and city streets bursting with bright red flame tree flowers.” [p.64] Throughout this section, he paints a loving portrait of a companion named Steve.

He recalls that the most important book for him as a young person was Gathas for Daily Life, which he describes as “a warrior’s manual on strategy…The use of such gathas encourages clarity and mindfulness, making even the most ordinary tasks sacred.” [p. 129, 130]. Likewise, we all can benefit from his contemporary version, Present Moment Wonderful Moment, and integrate these gathas into many of our daily activities.

He critiques the religious Establishment: “Every one of us—Man, Hien, Huong, Tue, Hung, myself, and many others—was unable to find a place in the Buddhist hierarchy. We were accused of sowing seeds of dissent when we challenged anything traditional. We are considered rabble-rousers who only wanted to tear things down. The hierarchy did not know how to deal with us, so they silenced our voices. For eight years, we tried to speak about the need for a humanistic Buddhism and a unified Buddhist church in Vietnam that could respond to the needs of the people. We sowed those seeds against steep odds, and while waiting for them to take rout, we endured false accusations, hatred, deception, and intolerance. Still we refused to give up hope.” [p. 30]

He points out the perennial danger of consumerism: “We, too, have become so accustomed to our way of life with its conveniences and comforts that we allow ourselves to be colonized.” [p. 92]

He shows how teacher and students inter-are: “I also long to preserve individual meetings between teacher and student in which the student enjoys the teacher’s complete attention, the kind of attention that calls forth the student’s mindfulness. The teacher also benefits from a student who is completely present.” [p. 118]

Speaking of someone dear to him, he affirms, “I know she isn’t dead. Someone like her can never really die. She lived a beautiful life, active and rich in faith. All of us carry her image within. We grieve her passing, but we smile tenderly every time we think of her.” [p. 54]

These pages give a foundation to his later claim in The Raft is Not the Shore that we need access to a resistance community, wherein we can cultivate the inner life and regain our sovereignty. He observes, “Small, quiet places are more conducive for spiritual experiences. In such a space, meeting the Buddha becomes an encounter with your own true self.” [p. 117]

May we cultivate our sangha with care, courtesy, and consideration!

*Phuong Boi, Vietnamese for “fragrant palm leaves,” was the name of Thich Nhat Hanh’s monastery in highlands of Central Vietnam.