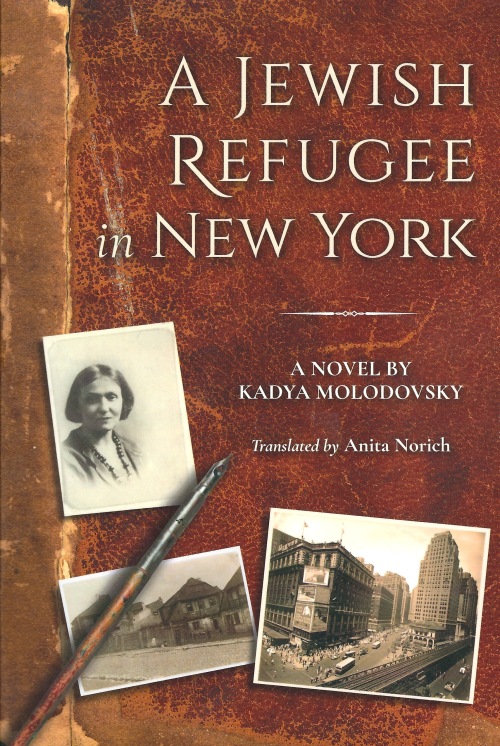

Kadya Molodovsky, A Jewish Refugee in New York: Rivke Zilberg’s Journal

Translated by Anita Norich

The accomplished Yiddish writer Molodovsky wrote this novel in serialized form in 1940-41, knowing obviously what was happening at the time to her friends and family in Europe. But it was impossible for her to imagine the eventual enactment of a “Final Solution.” We readers in 2019 know what was to happen in the years following Rivke’s arrival and year of adjustments in the U.S. This makes the author’s portrayal of American superficiality even more piercing and jarring. Yet this theme of clueless nonchalance also interrogates also our present: Besides the consistently awful headlines each day, what unimaginable catastrophe is looming around the corner?

_____________

The women talked a lot about themselves and didn’t give me the slightest opportunity to tell them how I came to be a refugee. 2

When he dances [like Benny Goodman] all I can think about is that my mother was killed by a bomb, and I don’t know what’s happening with my brothers, although I’m sure they’re not dancing now. I have no idea what’s become of my father either. I’d go to the ends of the earth to avoid Marvin’s dancing, but where can I go? 8

I thought they were getting ready for a Purim ball, but they explained that they were planning an event for war victims. I couldn’t believe how happy they were. They joked and talked and ate [cake]. No matter what’s going on, there’s always cake. If they’re having a card party—cake; a birthday—cake; collection for those suffering in the war—more cake. 12

And on top of everything else, I was upset with Red. When he came, I told him about my father’s letter. “You’re here, not there,” he answered. I could see in his face that he wasn’t the least bit concerned. Red saw that it upset me, and so he added, “What can you do?” I don’t know if Americans are heartless or they just pretend to be. I have no idea. They’re probably pretending. 50

“What are relatives nowadays. Once upon a time an aunt was an aunt, I brought everyone of my nieces and nephews to America. So now they make an appearance only if they need something.” 53

I’ve learned at least one thing in America. Whether things are good or bad, the first thing you have to do is smile. 65

She left to go get dressed. On Shabbos she always goes to the movies, and she didn’t want to be late. 91

Selma and Ruth wee completely absurd in showing one another their makeup cases. 93

My uncle calls the cost of Selma’s wedding a “conflagration.” 114

Selma was very unhappy because [Mendl] chose such a terribly hot day to go to the hospital. 139

She was wearing seven gold necklaces, one under the other, so that her whole chest was covered in gold. She wears even more makeup than Selma: on her cheeks, her lips, her eyebrows, even her nose. 154

“In these times, when Jews are suffering throughout the world, we’re happy to be in America, and we’re proud to have such personages as Mr. Shamut.” 163

Even when I don’t think about my mother, I never forget her. And I never forget that my father is in Lublin sleeping on the ground in a barn or that Janet is blind. How can anyone forget all these things? But I’ve learned to keep quiet about it, to cover it up with white shoes, with factory work, and with living on Grand Street. Sometimes, if I laugh too loudly, I hear my laughter and am amazed. And in an instant, I’m more in Lublin than in New York. 166

_____________

Below his breath, the Jew asks of his gentile neighbor: “If you had known, would you have cried in the face of God and man that this hideousness must stop? Would you have made some attempt to get my children out? Or planned a skiing party to Marmsich?”

— George Steiner, “A Kind of Survivor”