Review of Mark Philip Bradley, Vietnam At War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

1.

In our history books we refer to “the Vietnam War,” which fixated American attention for a decade, if not more. Some common associations and recollections of that period from the tumultuous Sixties to 1975 are of Presidents Nixon and Johnson, our POWs and MIA, napalm and Agent Orange, the antiwar movement, William Calley and the My Lai atrocity, the 1968 Tet Offensive, and the vets grappling with PTSD after their unceremonious return to the U.S.

It is the virtue of University of Chicago historian Mark Philip Bradley’s Vietnam at War to focus on how the Vietnamese perceived and responded to their successive struggles, wars, and cataclysms: from the long decades of French colonialism, to the post-World War II battles after France’s reconquest, to the supposedly temporary division of North and South Vietnam pending reunification after an election in 1956, to the rise of the National Liberation Front in the south, to the full-scale land invasion by the United Sates in 1965, and that war’s 1975 aftermath.

For an American who has read some of the books from “our side” (veterans’ accounts, political memoirs) or seen any of the U.S. films on the war period, this book would be a worthwhile investment of time and energy. More of us, from several generations, need to reckon with the history and present of a people whom we formerly dehumanized as “gooks” and “slopes,” but with whom we nevertheless “inter-are,” in the formulation of Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.

2.

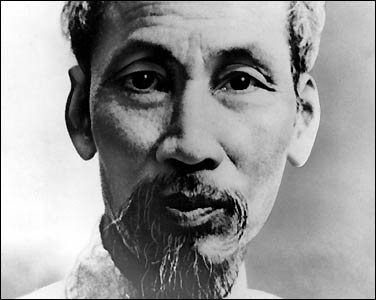

With the French domination of Indochina since the late 19th century, the Vietnamese were faced with excruciating questions: How could this horror come to pass? Why were the Vietnamese able to be dominated and exploited by the French? Bradley notes that, “[d]espite the self-serving French claims to be carrying out a mission civiliatrice in Vietnam, colonial policies affected the lives of Vietnamese peasants in devastating ways and significantly increased the potential for class tension and disorder in the countryside.” [16] Multiple perspectives and answers emerged from the early 1900s to address this degradation of Vietnamese society. Modernizers, reformers, radicals, and revolutionaries all developed accounts of why it had happened and what must be done to gain freedom from colonial rule. In 1926 one of these early critics of the French, Nguyễn Ái Quốc, later to become Hồ Chí Minh, stated, “The liberation of the proletariat is the necessary condition for national liberation.” [6]

During World War II, Japan took over France’s control of Vietnam, during which an estimated 2 million Vietnamese died from famine. During this time the Việt Minh asserted itself as a national independence movement led by Hồ and sought a broad coalition for “national salvation.” Bradley comments, “Throughout the Second World War, the [Việt Minh] sought to portray themselves in Confucian and patriotic terms that they believed would resonate with wide sectors of the Vietnamese urban and rural population. The leadership consciously drew on Confucian models of personal ethics and selfless sacrifice to society. [Hồ Chí Minh’s] carefully crafted public persona projected all the desirable qualities of the Confucian ‘superior man’: rectitude, sincerity, modesty, courage, and self-sacrifice.” [36] After the Japanese were defeated, the Việt Minh declared independence with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The French, however, were intent on regaining what had been theirs, particularly in the southern part of the country, where they had made profitable investments in tea, coffee, and rubber. Thus, the groundwork was laid for the “French War.”

3.

The French lured the former emperor Bảo Đại to be their figurehead and the United States became involved by largely subsidizing France in her colonial aims. Bradley argues that the “racialist lens through which the Americans viewed the Vietnamese heightened the strategic importance of the French war for American cold war diplomacy. If the Vietnamese were incapable of self-government and susceptible to external direction, as most US policy makers believed, evidence of the communist orientation of the leaders of the Democratic Republic meant they could be little more than puppets directed from Moscow or Beijing, with alarming implications for the American cold war rivalry with the Soviet Union.” [55] Joseph Stalin had no trust in Hồ; but the recently victorious Communist Party in China was supportive of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s aspirations. By 1953, the French had lost 150,000 men (note that 58,000 American service people died in Vietnam) and in less than a decade after World War II, the DRV dealt the French a death blow at the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954.

According to Bradley, “Without question the DRV emerged from the French war with increased prestige. The regime had defeated the French—an outcome almost unimaginable to many contemporary Western observers when the war began—and had built a strong and seasoned military force. [Hồ] became an almost larger-than-life figure. Even those Vietnamese who opposed his socialist regime acknowledged his political skills and could not deny the larger symbolic resonances of the victory at [Điện Biên Phủ].” [68] Further, Hồ’s DRV strategically emphasized the victory over the French in a narrative of sacred struggle that gave pride of place to revolutionary sacrifice.

4.

However, with the Geneva Accords between Vietnam and France, independence was delayed temporarily until elections and reunification of the North and South could be held in 1956. Hồ was confident of victory in the proposed election, which never came to pass, as it was ignored by Ngô Đình Diệm, backed strongly by the U.S. that was opposed to any prospect of Communist leadership in a united Vietnam. The U.S augmented its previous investment in French control: “More than $1 billion in subsidized US exports flowed into the South between 1956 and 1960 to ensure the availability of inexpensive consumer goods in urban areas….The size of the US aid programme and its embassy in Saigon was second only to the American commitment to South Korea.” [84] Diệm brutally repressed any opposition in the south, which led to the rise of the southern National Liberation Front, backed by the DRV, which Bradley notes, “provided a viable and popular means not only to challenge the [Diệm] government but also to imagine an alternative state and society for southern Vietnam.” [101] The Kennedy Administration continued to increase U.S. commitment with advisors and military aid, and still Diệm was unable to maintain control. A crisis erupted in 1963, with Buddhists taking the leadership in protesting Diệm’s oppressive regime. By November 1963 Diệm was assassinated during a military coup (with U.S. foreknowledge); within a year, the Tonkin Gulf Incident was exploited by Kennedy’s successor Lyndon Johnson to attack the DRV. A year later, Operation Rolling Thunder had begun and hundreds of thousands of troops were arriving in South Vietnam.

5.

During the war 25% of all U.S. economic aid went to South Vietnam. The United States’ presence in South Vietnam radically transformed the lives of the Vietnamese. American-style consumerism and pop culture found its adherents in the Vietnamese middle-class, leading to generational conflicts. Bradley notes that “[t]he bombing, shelling, and ecological warfare that characterized American military strategy in southern Vietnam took a huge toll on the fabric of rural society, literally depopulating huge swaths of the courtside as villagers moved to refugee camps and urban areas.” [140-141] The U.S. shored up South Vietnam’s successive corrupt governments but after the Buddhists were crushed in 1966, there was no chance of another political force to challenge the government except the National Liberation Front. South Vietnam’s governments were opposed by the NLF, not all of whom were supportive of or interested in a socialist future. Some members of the NLF were bothered by domineering Vietnamese coming from the north to direct the southern struggle against the US and its SVN “puppets.”

In war-time, people think simplistically of two sides: ours versus theirs. Bradley points out that the NLF was more complicated than either the American proponents or antagonists of the US war were able or willing to see: “Without question, the Front had deep southern roots and spoke to profound discontent with the political and social order under Ngo Dinh Diem. It also quickly became dominated by Hanoi, a role that the North went to great pains to hide. For many in the southern movement who saw the NLF as a continuation of the larger struggle for Vietnamese independence and had given their allegiance to the DRV in the French war, this was not a particular problem. But for others it would be.” [100]

6.

Bradley chronicles how the U.S. war gradually came to an end: the pivotal 1968 Tet Offensive, Nixon’s program of Vietnamization, and peace negotiations in Paris. By 1975, the North Vietnamese army entered Saigon, and the war was over. Vietnam at last became unified. Though the now Socialist Republic of Vietnam had grave problems to face, their wars weren’t over, as the country became belligerents with Cambodia (under the Khmer Rouge) and China (Cambodia’s principal ally). Vietnam’s ultimately decade-long occupation of Cambodia further drained an already weakened economy. In 1986 a policy of đổi mới was instituted, which sought to liberalize the economy. Yet, Bradley observes, “With its new-found economic prowess, however, have also come problems: a growing gap between the wealthy and the poor, rampant corruption within the state and party over the spoils of the economic reforms, gender differentials in employment and political participation, and a significant deterioration in providing health care and educational access for all its citizens, what the Vietnamese socialist regime for all its peacetime problems did best.” [178]

Vietnam, Octoober 2009 Michelle Conley

7.

Throughout his succinct survey, Bradley stresses the tensions, contradictions, paradoxes, and ironies the Vietnamese experienced as they attempted to grapple with the questions of where they’ve been (vis-à-vis their colonized past), what they are (in the post-war period with a socialist government and economic renovation), and where they want to be in the future.

In the United States the meanings of our Vietnam war are still researched, discussed, distorted, evaded, and contested. Bradley’s book on our former allies, enemies, and victims can inform, complicate, and enrich our own grappling with who we were then, as well as who we are now—in Iraq and Afghanistan.