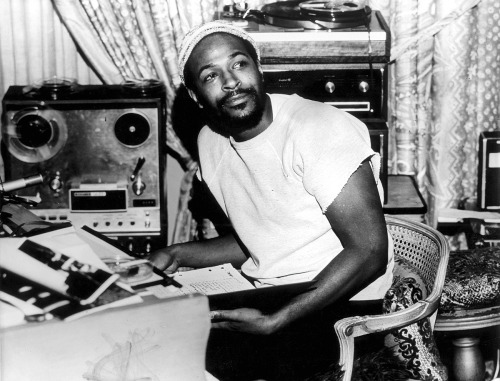

A Singer

In 1969 or 1970, I began to re-evaluate my whole concept of what I wanted my music to say…. I was very much affected by letters my brother was sending me from Vietnam, as well as the social situation here at home. I realized that I had to put my own fantasies behind me if I wanted to write songs that would reach the souls of people. I wanted them to take a look at what was happening in the world.

–Marvin Gaye

A Journalist

1.

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting. –Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

2.

She had first traveled to Vietnam in 1955, glad to see that the U.S. was making good on its aspiration to set the world right. By her second visit in 1963, she had sobered up. Seven years later, she began a stint as foreign correspondent for the New York Times, she had a hard time believing she was in the same country as before.

She had compassion and understanding for the U.S. troops, as she had for the Vietnamese being displaced, bombed, and killed by those same troops.

She knew she had privilege, of course; journalists could come and go, get the big story and give their careers a needed boost.

When she returned to the United States, she was obsessed. She admitted, “Turn the corner, people said to me in a kindly fashion. Forget the war. But I could not stop writing about it.”

And so she went to the out of the way places, to talk with ordinary Americans as to how the war had affected them. She learned that many Americans could not correctly say the name of the Vietnamese race. In a small Kentucky town, she asked the locals about their war dead, “Do you think that too much attention has been paid to the deaths in Bardstown?” She sought out American farmers, convinced that they, who so knew and understood the land, would care about the Vietnamese farmers being driven from their rice fields. She spent time with vets who had grown sentimental about Vietnamese women they had known but whose names they never learned. She met an antiwar activist: “He always wanted Americans to see the Vietnamese not just as victims but a people who loved their land, their trees, their poetry, their music, their language, their food. He thought the antiwar movement might have made a mistake in showing only the people in pain.” A veteran who participated in Dewy Canyon III in Washington told her that it was strange that the only people who seemed to be prosecuted for the war’s horrors were the wrong people.

She observed that as time went on and the war continued, Americans who had different views on the war seemed more contemptuous of each other than of the Vietnamese who were resisting the United States.

Her obsession was mirrored by the obsession of many of the people she met: vets, activists, people that could have been your next-door neighbors. One bureaucrat of the U.S. government who had worked in Vietnam did not appear to be obsessed; he told her, “the thing which I think I will remember about Vietnam when I am a hundred years old and will talk about it with my grandchildren is the countryside, how beautiful the women looked, and the food.”

After Gloria Emerson returned from Vietnam and spent three years roaming the country and interviewing her people, she finished her project, Winners & Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses, and Ruins from a Long War (New York: Random House, 1977). Therein, she urged, “Let the books be written so when all of us are dead a long record will exist, at least in a few libraries.” In 1976 she saw that the war was already being quickly forgotten.

Vietnam is just a confirmation of everything we feared might happen in life. And it has happened. You know, a lot of people in Vietnam–and I might be one of them–could be mourners as a profession. Morticians and mourners. It draws people who are seeking confirmation of tragedies….

Once I got so desperate-the Americans had started bombing Hanoi–I ran to the National Press Center where they give the briefings…a forty-year-old woman running through the streets in the middle of the night…and I wrote on the wall in Magic Marker, Father, forgive. They know not what they do. And I don’t even believe in God. Who is Father? Father, forgive, they know not what they do. But there were no other words in the whole English language.

If they found out it was me they would have sent me home. New York Times correspondents must not go running around at two o’clock in the morning writing, Father, forgive, they know not what they do. But afterward I thought how there’s no way…no one, no one to whom you can say we’re sorry. –Gloria Emerson, April 1971

An Actor

She must have touched a nerve

Jane Fonda’s FBI file

From the 60s & 70s

Is 22,000 pages long.

A Quaker

Maybe some U.S. citizens over 75

Remember the name “Norman Morrison”

But many people in Vietnam of all ages

Know that name

This young Quaker immolated himself in 1965

Deliberately close to Robert McNamara’s office window at the Pentagon

(Two years earlier Thich Quang Duc did the same act in Saigon

To protest the repression inflicted on the Buddhists)

One Vietnamese person said “We were such a tiny little country

It was like a gnat fighting an elephant

But someone from that huge country

Cared enough for us that he gave his life for us”

Now, gnats are still fighting an elephant

Or haven’t we noticed?

A Listener

“I’m sorry. We Americans have never taken responsibility for what we did.” –Lady Borton

Lady Borton worked for the American Friends Service Committee in South Vietnam in the late 1960s. A decade later, she assisted Vietnamese boat people and refugees. In the late 1980s and 1990s, she visited Vietnam several times, as she was intent on seeing what it was like to live with the peasants, especially the women. Her memoir, After Sorrow: An American among the Vietnamese, is a chronicle of her encounters with ordinary Vietnamese who gradually opened up to her and revealed their stories of resisting the French and the Americans. She visited people and friends in the southern, middle, and northern parts of the country.

Although he is not mentioned in her book, Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings occurred to me several times as I read. One of the Five Wonderful Mindfulness trainings calls for Deep Listening. It is Lady Barton’s deep listening to the Vietnamese that constitutes a gift to U.S. citizens whose socially conditioned ethnocentrism on the subject of the Vietnam War often begins with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and extends to concern for American military personnel Missing in Action. Ms. Barton brings the experience of the Vietnamese to our attention.

Here is some of what she heard …

“Now I’ve turned fifty-five and retired. I have a new grandson to rise! Do you see, Little One? Being able to raise our grandchildren—that’s what ‘peace’ means.”

“Nguyen Hue taught us we could fight for a thousand generations.”

“Oh my, when Uncle Ho died in 1969, the bombing in the South was ferocious. As if the Americans thought bombs could break our will!”

“How can a house made of thatch like this withstand American bombs?”

“We did everything! We climbed mountains, we hid under rivers. We captured prisoners. We carried ammunition. We trained ourselves to use weapons. We guided the soldiers when they wanted to attack the American base at Binh Duc. We were the guides, we were the spies. Don’t you see? Ours was a citizens’ war. We were the woman fighters.”

“We squatted like this in the bunker. The Americans were so far up in the sky, what did they know about our customs? They pushed buttons and dropped bombs. Then they flew away to fancy hotels in Thailand.”

“It was Agent Orange that drove us into the strategic hamlet. After Agent Orange, we had no fish, and we had nothing to drink.”

“[General Westmoreland] thought his American soldiers were better than the French. He thought the Americans would win their Dien Bien Phu at Khe Sanh. But that’s not what Khe Sanh was about! We didn’t want that hill!”

“How could we have weapons? We were poor! Our weapon was our wits.”

“I have plenty of food now, and I live with the peaceful sounds of birds and cicadas. Still, the sadness never leaves. Can you understand, Little One? Our sorrow comes and goes like the river. Even at low tide, there is always a trickle.”

“Always start your day with tiger balm, do you understand, Child? Go ahead, go on now, begin your day.”

“Don’t you understand, Little One?” Second Harvest said, gesturing toward the creek and the house with its ladder of light lying on the fresh water urns under the hatch eaves. “This is all we wanted.”

“Uncle Ho told us we must study tirelessly, from books, from each other. He said that as soon as we conquered one accomplishment, we must press on to the next if we were to maintain our independence.”

“You will transplant [rice] with us for days, but we’ll do this for weeks. And then for years.”

“If I get a chicken—a plump chicken—and give it to you, will you raise it on your farm in America?”

A man, Senior Uncle: “This is the only picture of me young. Give it to your father. Tell him to come live with me in Ban Long. I am his younger brother. I will take care of him in his old age.”

“We should have apologized to the French and the Americans after their defeats. After we break our heads against each other, we must recognize we are family.”

“When you return home, give my regards to your father. And give my best wishes to the American people.”

“Don’t forget us.”

A Boxer

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No, I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would put my prestige in jeopardy and could cause me to lose millions of dollars which should accrue to me as the champion. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality.…

If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. But I either have to obey the laws of the land or the laws of Allah. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.

–Muhammed Ali

This page is part of my book, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.