Leland Poague, ed.Conversations with Susan Sontag

University Press of Mississippi, 1995

Sometimes I feel that, in the end, all I am really defending—but then I say all is everything—is the idea of seriousness, of true seriousness. What strikes me is how unambitious and superficial most American literature is. 245

I write to be part of literature, not for other people. 262

Reading these interviews, I was reminded how clueless I was as a Bellarmine graduate. It was my senior week, 1982, no classes, and I was sitting in the cafeteria waiting to lunch with James Petrick and Paul Fleitz, and prof and poet and Merton intimate Ron Seitz sat beside me and asked me what I wanted to do now. I mumbled something to him, and he offered me a wry smile as he said, “So you want to be an intellectual, don’t you?” Yes, Ron, I did, but had precious few models.

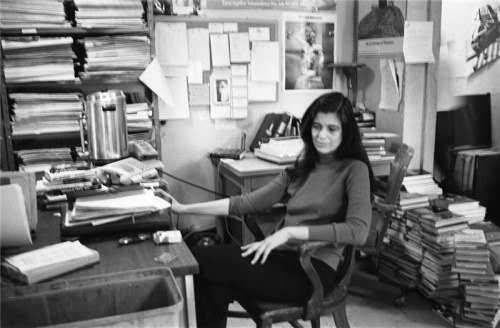

I became keenly interested in the work of Susan Sontag quite late, 2003, in fact, while reading her speech for an award in which she linked the witnesses of Oscar Romero and Rachel Corrie, the latter who had been bulldozed to death by an IDF soldier while serving as a volunteer wit the International Solidarity Movement. Later that year, I and friends from St. Louis went to Palestine and gave time with the same organization. I read many of her essays which were posted at Znet in the following years. A “gluttonous reader,” Sontag reminded me of Edward Said and George Steiner, whom I began reading in the 1990s.

The following excerpts spoke to me: first, what some of her interviewers made of Sontag, and, second, some of her reflections on themes important to me over the years….

_______________________

Bellamy: No one could have been more charming and cooperative. 35

Raddatz: If I had to apply the word “intellectual” to a single person, only she would come to mind. She has a lightening-like joy, an inexhaustible curiosity about events and processes even of the most remote type… 88

Lesser: Her own tone, however, is one of eminent rationality. If she is the modern version of the nineteenth-century sage, then she is certainly a toned-down Ruskin, a sane Nietzsche—and in fact a great part of her appeal as a stylist lies in that reasonable tone of certainty, that restrained assertiveness, that assurance of her own well-groundedness. 92

Manion and Simon: Sontag is persuasive because she conveys an impassioned involvement with her subject. To a variety of cultural concerns, Sontag brings the same rigorous scrutiny. 206.

_______________________

Buddhism: It seems to be quite convincing to argue that Buddhism is the highest spiritual moment of humanity. 116

Buddhism: One of the beautiful ideas in Buddhism is that if you are in fact at a point in your life where there is no suffering, then it is your duty to go and find some, to put yourself in contact with it. There are, as it were, duties about being human. You don’t have a duty to be as unconscious as you can possibly be. But modern society makes some states of unconsciousness seem very desirable. Television is a perfect institutional form of the mandate to be not very conscious. 244

Canon: Early modernists like Rimbaud, Stravinsky, Apollinaire, Joyce, and Eliot showed how “high culture” could assimilate shards of “low culture.” 68

Canon: What I understand by literature implies that a book will have an audience thirty or fifty years after it’s published—which means that most books acclaimed as literature when published are not part of literature. Whether one’s own writing is part of that tiny body of work that is valuable enough still to be read by the end of the century—this haunting ambition makes other calculations seem beside the point. 195 [see H. Bloom]

Canon: The fact that plurality is a part of literature—the dialogue among books. Both Austen and Beckett. We learn that there are many different ways to be, many temperaments…and the fact that to care about literature is to feel at home with the idea that some things are better than other things and a few things are better than everything else. 201

Canon: Literature comes from emulation. 204

Canon: I have a very strong sense of the canon. I find it impossible to think without the notion of a canon. I never even was aware of it until it began to be challenged, of course, but then I realized that the notion of the canon is essential to me. 240

Canon: The project of consciousness is basically a historical project. It is based on an accumulation of understanding and on consensus, which stipulates what it is to be human. It also has to do with an idea that there are better ways of being human as opposed to less good ways of being human, and the idea that there is a range of choices in the very form of being human. It has to do with the idea that there is memory. That there are records, and that there are efforts and versions of this project of consciousness. 241

Elitism: I think I am setting the bar higher, as athletes do. I’m more self-conscious, more conscious of my standard. I’m in a sort of competition with myself, which is not an innocent relation to one’s own work. 225

Elitism: It seems to me inconceivable that some values would not be acknowledged as superior to mere values of entertainment or distraction. I don’t see how in the world anyone could say it is not better to be a more profound person, or a more feeling person, or a more compassionate person, or a more sensitive person. 243

Elitism: Passion: I think we have to say: It does not matter if there are only five thousand people in the world who care about these things. Then that is all there is, and we could be like the Irish monks in the Dark Ages, who were just copying the classics and keeping them alive, perhaps with a hope there will come a completely different time when these texts will be meaningful to a much larger number of people, and when they could be an inspiration for some kind of cultural renewal. 249

Elitism: We are required to continue to make an effort to invite people in who are willing to do the work and to accept the differences in their own lives and their own consciousness that these loyalties will imply. It is a question of recruitment just as you recruit people into a religious order. 249

Engaging: Chekhov said that the writer’s main relation to politics should be one of flight, and that you should never allow yourself to become captured by other people’s demands that you express a progressive point of view. 216

Idology: One must never love States, any State; I think that’s the first duty of an intellectual: not to love a State. 152 [see Simone Weil on the Great Beast]

Intellectuals: In my view, the only intelligence worth defending is critical, dialectical, skeptical, desimplifying. And intelligence which aims at the definitive resolution (that is, suppression) of conflict, which justifies manipulation—always, of course, for other people’s good, as in the argument brilliantly made by Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, which haunts the main tradition of science fiction—is not my normative idea of intelligence. 77

Intellectuals: Intellectuals distinguish themselves from other people in that by constant reflection of interpretation they leaven reality. 94

Intellectuals: What we have to get away from is shame at being a bourgeois intellectual. Everybody has been made to feel guilty about that. 110

Intellectuals: Ethics: This society is a hypocritical society; we must unmask this hypocrisy, but not under the flag of nihilism. The dissidents always have a very moralizing discourse. Our society has a very amoral discourse: happiness, buying power, consumption. So, we are caught between these two terms: nihilism and consumerism. 105

Intellectuals: Voltaire is perhaps the first intellectual in the modern sense; that is, he wrote plays, poems, novels and essays. He was involved in all kinds of intellectual activities, questions of conscience, the equivalent of demonstrations and petitions. But he went even further in the Calas affair, etc. It was this vocation of being at the same time an artist, a creator, or writer, a person of conscience who gets involved in moral and political questions that was invented here [in France]. And that has a certain prestige in France, even now. 146-147

Intellectual: I think a true intellectual is never at home. To me, being an intellectual means seeing things in a complicated way. One lives on the boundary, one is aware of many claims, many alternatives, and that precludes being at home. I accept being uncomfortable, I also don’t know how else to be. 235

Intellectual: It’s an enormous responsibility. It seems to me essential to have some intellectuals in the dominant empire on the planet playing a critical or adversarial role—one of the things that intellectuals, at last since Voltaire, are thought to do. It’s true that most intellectuals are conformist, like most people. But I hope there will continue to be some North American intellectuals who will keep alive a more complex and more critical attitude towards this society, which has not only its strengths and good points, but a great many defects, and has behaved rather badly toward the rest of the Americas. 236

Intellectual: Since Diderot and Voltaire this has become the vocation of the modern writer: to advance critical or adversarial ideas about culture. 238

Learning: The real of life of the mind is always at the frontiers of “what is already known.” Those great books don’t need only custodians and transmitters. To stay alive, they also need adversaries. The most interesting ideas, after all, are heresies. 75

Learning: We were taught to be very close readers [at the University of Chicago]. We were taught incredible reading skills: to be able to examine a text thoughtfully word by word. (One might spend three class hours on two sentences.) 273

Learning: I didn’t think, and do not now think, that the main job of an education is to teach the student to be independent. The point was to learn; you have your whole life to be independent. I thought life should teach you to be independent. 276

Learning: We weren’t expected to turn in papers any more than Socrates’ students were expected to turn in papers. 277

Reading: She read The Second Sex in 1951 and became very militant. 31

Reading: Most young readers—high school and college students—will tell you that they find older novels too long. They find it hard to read Dickens or James or Tolstoy or Proust. They want something that’s faster and less descriptive. 38

Reading: To grasp the parallels and allusions and the play with The Odyssey when you read Joyce’s Ulysses adds to your pleasure. It’s another level of reading, another aesthetic game. But Ulysses certainly stands on its own without that knowledge. 47

Reading: How to read and why: Marxist thinking is dated. We have different, new problems, about which Marx didn’t say anything. But he has given us certain keys, certain methods of analysis, that must not be rejected. I think that you have to be for “master thinkers,” if we ask of them, not the illusion of an ideal society, but help in analyzing things. 104

Reading: On Beauvoir’s The Second Sex: It remains the greatest effort to pull together all the feminist arguments. Even if parts of the book are questionable, it is the great feminist work. It was written in’47, one evolves, but it is always this book to which one must refer. 155

Reading: My library is what is in my head. Of course, like any person who’s had a traditional education, I prefer hardcover to paperback because I like the way hardcover books feel in my hands; but basically I don’t care at all about the difference. Any book, in any edition, as long as I can read it. 184

Reading: What I like about Barthes is that he is first of all a writer. When I read someone like Kristeva I felt that the academic cast of it is a barrier to me. 209

Reading: Van Gogh is another important presence for me. He matters more to me than any living American writer. 223

Reading: I love Emerson, the first great American writer. 223

Writing: The free creative writer acts as a kind of freely suspended conscience. Whenever I sit down at the typewriter, it is always discovery work too. I don’t sit down simply to write down what I have just thought out. It is much more a new and ever developing, previously unknown, dialogue, whether with living or dead persons or even with the structures of the world in which I now life. 95

Writing: The greatest effort is to be really where you are, contemporary with yourself, in your life, giving full attention to the world. That’s what a writer does. I’m against the solipsistic idea that you find it all in your head. You don’t. 108

Writing: I find writing very desexualizing, which is one of its limitations. I don’t eat, or I eat very irregularly and badly and skip meals; and I try to sleep as little as possible. My back hurts, my fingers hurt, I get headaches. And it even cuts sexual desire. I find that if I’m very interested in someone sexually and then embark on a writing project, there’s pretty much a period of abstinence or chastity, because I want all my energy to go into the writing. But that’s the kind of writer I am; I’m totally undisciplined, and I just do it in long, obsessional stretches. 120

Writing: Proust said [to Cocteau]: “You clearly could be a great writer, but you must be careful about society. You mustn’t go out, or go out a little, but don’t make it a main part of your life.” I’m not saying that one has to be in a cork-lined room, but I think that one has to have enormous discipline. And the vocation of a writer, like that of a painter, is in some deep way antisocial. 129

Writing: You have to create your own space which has a lot of silence in it and a lot of books. 134

Writing: I think the highest duty of a writer is to write well—to leave the language in better rather than worse shape after one’s passage. That’s an ethical obligation. Language is the body, and also the soul, of consciousness. Our ultimate responsibility is to act chivalrously toward the language we inhabit. 201

Writing: But in fact I never start with a subject. What starts me is a voice, or a word. Often it’s just a word. 203

Writing: I write essays first because I have a passionate relationship to the subject and second because the subject is one that people are not talking about. The writers or artists I write about are not necessarily those I care most about (Shakespeare is still my favorite writer) but those whose work I feel has been neglected. 213

Writing: Writing is solitary—you do it alone, it is perhaps the most solitary occupation there is. But it’s not private; it is simply work done in private. I never think of the activity of the writer as a private activity. You see, I think that the good writer, choosing to write, is always making something social in standing for excellence, standing for a certain hierarchy of values, protecting the language—that’s our medium, and ultimately, we want to prevent it from decaying or deteriorating. We want to leave the language in a perhaps slightly better shape because of our passage through it in all our books… Rather than in worse shape. The writer stands for singularity, the writer stands for an individual voice. The existence of good writing stands for an independent or autonomous life, for self-reliance. These are all public, civic, moral values that don’t necessarily involve the kind of communal or civic engagement that you’re talking about. 217

Writing: And I think that we do live in a time that we all experience in some way as a time of crisis, as a time in which much has been destroyed and much has been lost, and much more is going to be lost, and we experience the demand on us as writers, and I think also—and why not—as human beings, to be both a radical demand and a conservative demand. It’s radical because we want to help change what is evil in our society and bring to birth something that will help assist in the correction of certain fundamental wrongs and injustices. And we are also conservative because we know that in this process so much is being destroyed that we cherish and that we value. It’s very difficult to call ourselves either conservative or radicals, because we understand both impulses. And that informs one’s situation as a writer. One is part of a process of civilization and one is part of a process of increasing barbarism. 219

Writing: In all these cases, Van Gogh, Joyce, Canetti, it is really a question of an enormous self-confidence, of really feeling something like a mission and of seeing it partly as a religious vocation. Whereas now, writing for most people, including some very talented writers, is a career, it is not a vocation. 247