H. Leivick

I have often felt that instead of writing my autobiography I would like to write the biography of my poems. I mean, tell the life story of some of my poems…

Sholem Aleichem

If you’re looking to buy something, I’m afraid I’m all out of stock, unless I can interest you in some fine hunger pains, a week’s supply of heartache, or a head full of scrambled brains.

Oh, my dear Lord, I thought: they say you’re a long-suffering God, a good God, a great God; they say You’re merciful and fair; perhaps you can explain to me, then, why is it that some folk have everything and others have nothing twice over? Why does one Jew get to eat butter rolls while another gets to eat dirt?

… unless, that is, the Almighty looks down on us and says, “Guess what, children! I’ve decided to send you my Messiah!” I don’t even care if he does it just to spite us, as long as He’s quick about it, that old God of ours!

Melech Ravitch

A [second] Bible must take in not only fragments, words, figures, statistics, lists and what not which already exist—it can also have things written of it, even by quite nameless writers…The Bible takes in fragments of history, fragments of stories and dramas, songs, poems, philosophy, aphorisms, chronology, letters statistics, constitutions, documents. These are the elements. Beyond that I can’t go.

Rachmil Bryks

I tried in my book Kiddush Hashem to picture Auschwitz in seventy pages. But I wrote the book over a period of six years, in pain and agony. And writing it I became a changed man. I didn’t sleep night after night. I lived through everyone’s separate torment. I experienced over again every happening I described. I was back in Auschwitz. When I did fall asleep I woke, screaming. I had dreamed I was in the ghetto or in Auschwitz.

Chava Rosenfarb

I have no idea that at the same time in the United States of America, Theodore Adorno has come out with the sweeping statement that to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. A meaningful, powerful declaration, but it has nothing to do with me. The rhythms surging inside me deny his statement. I think of my father, who prodded me to write, even in the ghetto. I think of the poet [Simkha-Bunim] Shayevitch, who wrote poems even in the camp, just days before he was sent to the gas chamber. They too deny Adorno’s statement.

[Shayevitch] became my first real mentor. He taught me not only to take poetry seriously, but to take myself seriously as a poet, to dig to the bottom of what was most deeply hidden inside me in order to give my verses a more original, a more powerful, dimension.

Itsik Manger

Pity Jews won’t read these books [about Warsaw ghetto rising]. Why recall their nightmares? Germans certainly won’t read them. Why recall their own bestialities? So we get the strange paradox, that neither the murderers nor their victims want to be reminded about it. Both want to forget.

Isaac Bashevis Singer

If we reach the time when Yiddish and Yiddish customs and folklore are forgotten, Hitler will have succeeded not only physically but also spiritually.

I’m sure that millions of Yiddish-speaking ghosts will rise from their graves one day and their first question will be, “Is there any new book in Yiddish to read?”

Eliezer Wiesel

I looked at myself in the mirror. A skeleton stared back at me.

Nothing but skin and bone.

It was the image of myself after death. It was at that instant that the will to live awakened within me.

Without knowing why, I raised my fist and shattered the glass, along with the image it held. I lost consciousness.

After I got better, I stayed in bed for several days, jotting down notes for the work that you, dear reader, now hold in your hands.

But…

…Today, ten years after Buchenwald, I realize that the world forgets. Germany is a sovereign state. The German army has been reborn. Ilse Koch, the sadist of Buchenwald, is a happy wife and mother. War criminals stroll in the streets of Hamburg and Munich. The past has been erased, buried.

Germans and anti-Semites tell the world that the story of six million Jewish victims is but a myth, and the world, in its naïveté, will believe it, if not today, then tomorrow or the next day.

So it occurred to me that it might be useful to publish in book form these notes taken down in Buchenwald.

I am not so naïve as to believe that this work will change the course of history or shake the conscience of humanity.

Books no longer command the power they once did.

Those who yesterday held their tongues will keep their silence tomorrow.

That is why, ten years after Buchenwald, I ask myself the question, “Was I right to break that mirror?”

1955 [Translation from Un di Velt Hot Geshvign (And the World Was Silent)]

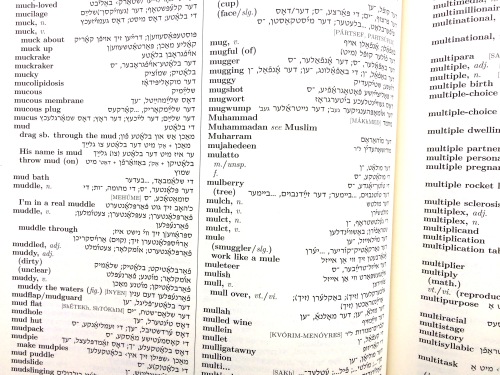

Photo at top: Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath and Paul Glasser, ed. Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary

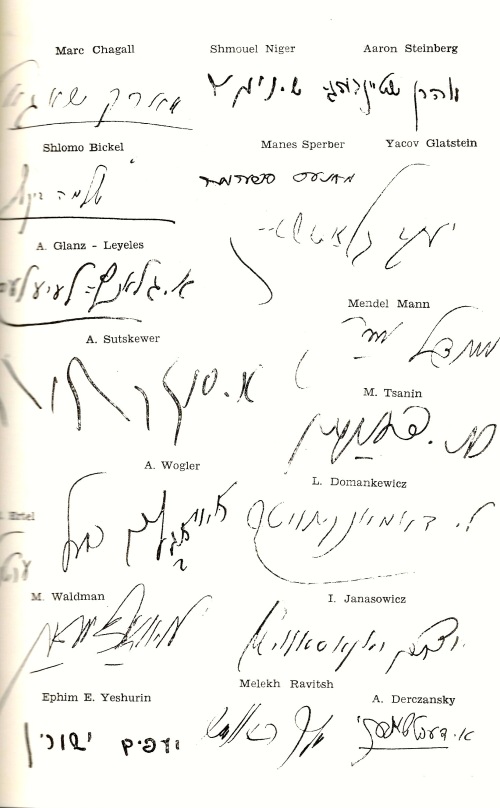

This page is part of my book, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.