I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.

—Franz Kafka, Letters

Though for us it’s absurd to cut our brother’s head off only because he’s become our brother and grace has descended upon him, still, I repeat, we have our own ways, which are almost as good. We have our historical, direct, and intimate delight in the torture of beating. Nekrasov has a poem describing a peasant flogging a horse on its eyes with a knout, ‘on its meek eyes.’ We’ve all seen that; that is Russianism. He describes a weak nag, harnessed with too heavy a load, that gets stuck in the mud with her cart and is unable to pull it out. The peasant beats her, beats her savagely, beats her finally not knowing what he’s doing; drunk with beating, he flogs her painfully, repeatedly: ‘Pull, though you have no strength, pull, though you die! ‘ The little nag strains, and now he begins flogging her, flogging the defenseless creature on her weeping, her ‘meek eyes.’ Beside herself, she strains and pulls the cart out, trembling all over, not breathing, moving somehow sideways, with a sort of skipping motion, somehow unnaturally and shamefully—it’s horrible in Nekrasov. But that’s only a horse; God gave us horses so that we could flog them.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

There [Communist bloc] nothing goes and everything matters; here [USA] everything goes and nothing matters.

—Philip Roth, Shop Talk

During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I

spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in

Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone ‘picked me out’.

On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me,

her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor

characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone whispered there) – ‘Could one ever describe

this?’ And I answered – ‘I can.’ It was then that

something like a smile slid across what had previously

been just a face.

—Anna Akhmatova, INSTEAD OF A PREFACE, Requiem

Our society ignored what was really going on in Chechnya, the fact that the bombing was not of terrorists’ camps but of cities and villages, and that hundreds of innocent people were being killed. it was then that most people living in Chechnya felt, as the still feel, the diabolical hopelessness of their situation—when, taking away they children, fathers, and brothers to who knows where and for who knows why, the military and civilian authorities said baldly (and still say), “Stop whining. Just accept that this is what the higher interests of the war on terrorism require.”

—Anna Politkovskaya, Putin’s Russia

The real victims of ‘America’s agony’ are millions of suffering people throughout much of the Third World. Our highly refined ideological institutions protect us from seeing their plight and our role in maintaining it, except sporadically. If we had the honesty and the moral courage, we would not let a day pass without hearing the cries of the victims. We would turn on the radio in the morning and listen to the voices of the people who escaped the massacres in Quiche’ province and the Guazapa mountains, and the daily press would carry front-page pictures of children dying of malnutrition and disease in the countries where order reigns and crops and beef and exported to the American market, with an explanation of why this is so. We would listen to the extensive and detailed record of terror and torture in our dependencies compiled by Amnesty International, Americas Watch, Survival International, and other human rights organizations. But we successfully insulate ourselves from the grim reality. By so doing, we sink to a level of moral depravity that has few counterparts in the modern world….

—Noam Chomsky, Turning the Tide

Our society isn’t a society anymore, it is a collection of windowless, isolated concrete cells…. The authorities do everything they can to make the cells even more impermeable, sowing dissent, inciting some against others, dividing and ruling. And the people fall for it. That is the real problem. That is why revolution in Russia, when it comes, is always so extreme. The barrier between the cells collapses only when the negative emotions within them are ungovernable.

—Anna Politkovskaya, A Russian Diary:A Journalist’s Final Account of Life, Corruption, and Death in Putin’s Russia

You probably think I’m writing all this to stir your pity. My fellow citizens have indeed proved a hard-hearted lot. You sit enjoying your breakfast, listening to stirring reports about the war in North Caucasus, in which the most terrible and disturbing facts are sanitized so that the voters don’t choke on their food. But my notes have a quite different purpose, they are written for the future. They are the testimony of the innocent victims of the new Chechen war, which is why I record all the detail I can.

—Anna Politkovskaya, A Dirty War: A Russia Reporter in Chechnya

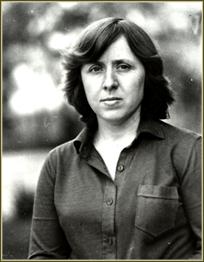

Svetlana Alexievich