What You Understand Depends on Where You Stand

For Brent Fernandez and Brett Schrewe

Night Flight to Hanoi is an account of Jesuit Daniel Berrigan’s odyssey in late January and early February 1968, when he and historian Howard Zinn traveled to Hanoi as representatives of the American peace movement. Their aim was to bring home three U.S. pilots whom the North Vietnamese had released. The narrative includes his decision to go, the waiting, the arrival, the tours into the grotesque and destructive displays of US military power, the testimonies of Vietnamese humanity and ingenuity, the meeting with the pilots, and the unelaborated denouement when the men are flown home—contrary to the wishes of the North Vietnamese—on a military plane. He and Zinn went in good faith around the world to promote peace between the two countries; the U.S. government, however, violated the agreement.

What is bracing in this account is Berrigan’s journey of solidarity, risk-taking, and accompaniment (example: sitting in the bomb shelters with the Vietnamese). So, what matters after such exposure and confrontation over the course of several days?

Seeing matters: “I have seen the victims. And this sight of the mutilated dead has exerted such inward change upon me that the words of corrupt diplomacy appear to me more and more in their true light. That is to say—as words spoken in enmity against reality.” [22-23] How Berrigan’s Jesuit brother Ignacio Ellacuría stressed over and over the imperative to confront realidad.

Modesty matters: “Instructions upon return. Develop for the students the meaning of Ho’s ‘useless years.’ The necessity of escaping once and for all the slavery of ‘being useful.’ On the other hand: prison, contemplation, life in solitude. Do the things that even ‘movement people’ tend to despise and misunderstand. To be radical is habitually to do things which society at large despises.” [49] Radical, like being with the ill and dying, which Berrigan later embraced in his work at St. Rose’s Home in New York.

Truth-telling matters: “Numbed and appalled as we were on leaving that room, I think we knew beyond doubt that America would be accountable to history for a genocidal war, in violation of every international convention from The Hague in 1907 to Geneva in 1929 and 1949, on to the hot pursuit of the Nazi ‘war criminals’ in Nuremberg.” [68-69] That was the Sixties; to that infamy can be added ongoing U.S. criminality, from Central America in the Eighties to Iraq spanning the Nineties and the last decade.

Social location matters: “What sort of proximity to actual war is required, if men [and women] are to become thoughtful and critical about their actions?” [94] “It is a bit like Selma—we are safe only among the victims. A law of history? Who was ever safe among executioners?” [112] As Rachel Corrie indicated, nothing can prepare you for an immersion in the Palestinian reality. There is no substitute for living with families suffering under military occupation.

Knowing what and where the real work is matters: “An adequate peace movement could not satisfy itself with assuaging the sufferings of the victims, by medical help at the point of impact. The radical work consisted rather in staying with conditions at home, trying as best we might to work changes upon a society in which military victims were the logical outcome of a ruinous, power-ridden national ethos in the world at large.” [69] Then and since, both Berrigan and Zinn did their part to interrogate and delegitimize that “national ethos,” a work that must be our own.

Loss of innocence matters: Upon departure from North Vietnam, Berrigan realized a rite of passage: “The fact was that, quite simply and unequivocally, we had graduated from innocence. We stood at the airstrip that night, a degree of sorts, at the ceremony of our Vietnam commencement. We looked down, and the ticket of our passage was a handful of flowers. Unseasonal, unexpected, fragrant, they glimmered in the darkness, the unlikely January blooms, celebration and portent. We had made it, the smiles of our teachers assured us.” [134] There are so many delusions and privileges to cut through, so many innocences that are but blindnesses, mainstream patriotism being a major one.

Berrigan mused about this quest: “Possibly, all these days will mean nothing spectacular—simply the taking up of the work of peace with more will and courage.” [110] A few months later, he would join eight others in the Catonsville Nine action in Maryland. For that civil disobedience, they would go on trial and be sentenced to years in federal prisons.

From the Vietnamese, Berrigan learned this proverb: “To one who has traveled four thousand miles, ten miles more are nothing.” [79]

Announcements

Laura Weis shared this with me from a class we had 16 years ago at SLU; this led to her going to hear Dan Berrigan at Cook Hall. I’m not the only one who keeps detailed files

“Why Must the Poet’s Mouth Be Bloodied, His Teeth Caved in?”

More than a decade ago, octogenarian Jesuit felon Daniel Berrigan spoke at the local Jesuit university (in the auditorium of the business school, no less). During the Q & A, Catherine Nolan asked him this question, “Dan, what have you been reading these days?” His response: “The Gospels and the poets.”

This came back to my memory as I read a book from the late 80s, Berrigan’s Poetry, Drama, Prose, edited by Michael True. I took particular note of Berrigan’s engagement with three poets: Ezra Pound, Denise Levertov, and Kim Chi Ha. About Kim, the Korean Catholic, Berrigan observed, “In South Korea, a poet writes a few lines—and the junto leans forward, all ears. He is arrested, rigorously judged, condemned. How can this be? Why are speech and writing charged with political and religious lightning? Why must the poet’s mouth be bloodied, his teeth caved in?” Though Lawrence Ferlinghetti sees poetry as a subversive art, U.S. poets don’t end up beaten in maximum security prisons.

One of Berrigan’s criticisms of Pound was, “[He] thought art was a saving act. It was as simple as that. He was a Pelagic through and through.” Yet, the Jesuit acknowledges at least six of [Pound’s many works as] absolutely irreplaceable—The Unwobbling Pivot, Personae, Selected Poems, Guide to Kulcher, The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius, The Women of Trachis.” It’s worth noting that Berrigan’s friend and later nemesis Ernesto Cardenal was greatly influenced by Pound’s poetics. How could Cardenal’s exteriorismo have emerged without the confrontation with Pound?

In a review of Denise Levertov’s prose works, Berrigan reported, “She tells of that comatose decade, the seventies, almost as though it hadn’t existed. She marches, keeps something alive, is personally dispassionate. There was work to be done, that was all. It little mattered that the work was despised or ignored or neglected. It was simply there, as evil was, as the world was; as hope was. She is passionate only about the issues, life or death.” At the beginning of the decade, Levertov made, like Berrigan did four years before her, the long trek to North Vietnam, and learned first-hand about Vietnamese resilience in the face of American savagery.

Only yesterday, a friend acknowledged how toxic the political climate and news are for her and her colleagues (working in the health field with endangered immigrants). She distances herself from some social media, tries to practice healthy detachment, for she knows, like many of us, an hour of reading bad news, however trenchant the critical analysis, only gets you so far. I sent her Thich Nhat Hanh’s poem, “The Good News,” as an encouraging reminder. And then there are Brecht’s lines, “In the dark times/ Will there be singing?/Yes, there will be singing/About the dark times.”

On Daniel Berrigan

1.

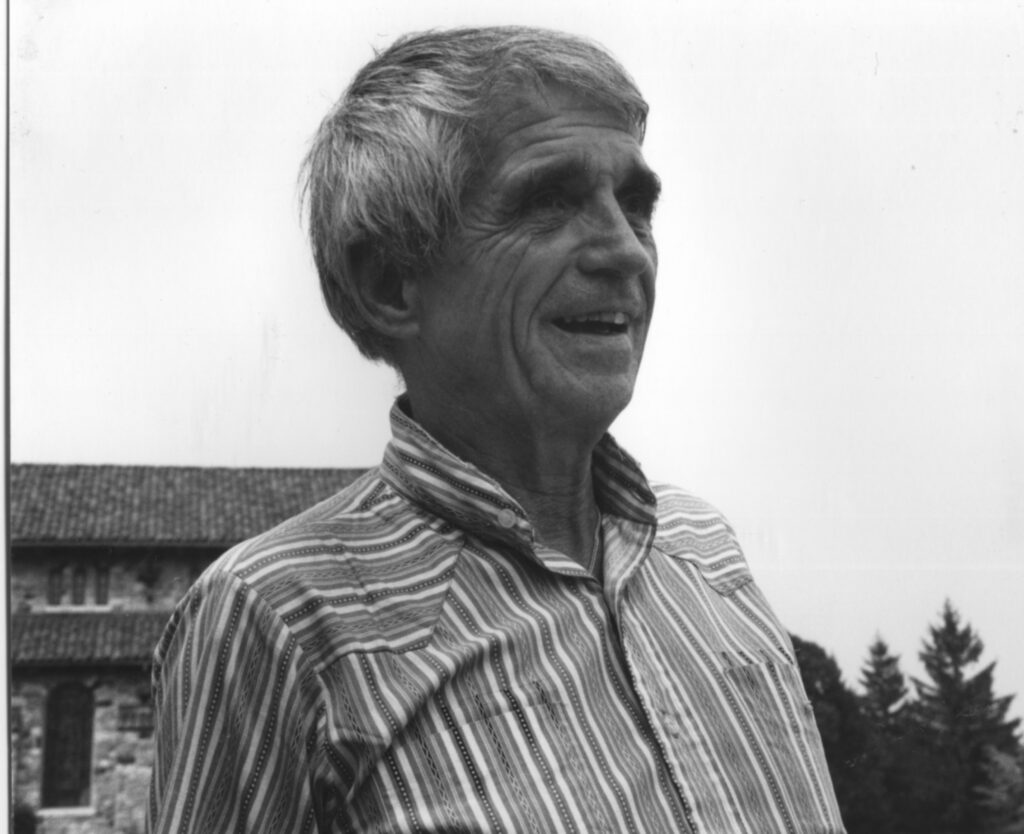

Some of Daniel Berrigan’s Whitmanian multitudes: Brother, uncle, jailbird, correspondent, chef, Jesuit, retreat master, playwright poet, peacemaker, mentor, reader, teacher, prophet, son, friend, logophile.

2.

In our age they they talk about the importance of presenting Christianity simply, not elaborately and grandiloquently. And about this subject they write books, it becomes a science, perhaps one may even make a living of it or become a professor. But they forget or ignore the fact that the truly simple way of presenting Christianity is—to do it. — Soren Kierkegaard

3.

And after each interview, the mother would invariably walk to the far end of the table, to a heap of photo albums laid there. Would take one of them in hand, gravely turn page after page, these images out of the national abattoir, the tortured, raped, amputated. The photos that stood horrid surrogate for the young men, absent from streets and homes and churches and factories. The disappeared generation. I could scarcely bear to look at the faces that dared look at such images, and not be turned to stone. How much can one bear? I did not know. But I sensed that the measure of what could be borne would be revealed neither by psychiatrist nor politician nor bishop. I must go in humility to these unknown, despised lives, upon whom there rested the preferential option of God. —Daniel Berrigan, on being in El Salvador

We are not to forget, to lose our hold upon the word of God as to our vocation (which is in effect much akin to the vocation of the prophet). To forget in this sense has the most serious moral consequence. Shortly or in the long run, the amnesiac falls in line. He is seduced and enlisted as votary of this or that illusion, ideology, hoax, of whatever empire. The latest war is “just,” the latest evil is the “lesser,” the current candidate of the political Olympus at long last will bring “change.”—Daniel Berrigan

4.

Don’t die, [Berrigan] would say. Come along, we need you. Don’t be a conscious integer in the empire’s spiritual body count. He made it seem as if resurrection and discipleship were synonyms. —Bill Wylie-Kellerman

No sophistic philosophying. No theological profundities. Rather, a direct and categorical imperative: we are not allowed to do harm to others. We are, as Tolstoy wrote, confronted with alternative ways of living: the Law of Love or the Law of Violence. Christians are to live by the Law of Love. — Earl Crow

No rhetoric. Simple talk, Gospel rooted talk. No notes. Compelling in honesty. He did not tell others what to do, only how and why he lived as he did. —Thomas Fox

No tweed jacket, no tie. Usually blue jeans and collarless shirts picked up at second-hand shops. No briefcase brimming with bibliography, no ponderous lecture, no sharp-edged questions, no ready critique snapping from his academic ego. No willingness to pay homage to academic convention. Just a profound respect for truth—and a passion to live it. With courage and humor, with humility and presence, with respect and love. —Robert Ludwig

His encouragement to retreatants is not to espouse his vocation, but to discover and live one’s own. His teaching and presence are not combative or preachy, but suggestive, invitational, evocative. He is a hearer and doer of the word in our midst, a powerful impetus to go and do likewise. — Robert Raines

5.

Judge: Father Berrigan, regardless of the outcome of these hearings, will you promise the court that you will refrain from such acts in the future?”

Berrigan: ”Your honor, it seems to me that you are asking the wrong question.”

Judge: ”Okay, Father Berrigan, what do you think is the proper question?”

Berrigan: ”Well, your honor, it appears to me that you should ask President Bush if he’ll stop making missiles; and if he’ll stop making them, then I’ll stop banging on them and you and I can go fishing.”

Sources

John Dear, ed., Apostle of Peace: Essays in Honor of Daniel Berrigan, Orbis Books, 1996.

Salvador passage: Daniel Berrigan, Steadfastness of The Saints: A Journal of Peace and War in Central and North America

After Last Night’s Bhagavad Gita Discussion

Daniel Berrigan once said to us

About trying to lead a nonviolent life:

“We do it because it’s the right thing to do

Not because it’s going to get us anywhere”

How deeply this cuts us!

Is the Jesuit priest crazy?

Because in these United States of Amnesia

We so want to get somewhere

We want success!

We want to know that we made a difference!

We want others to know we made a difference

(Is anyone keeping track of all our service hours?)

We wouldn’t mind beefing up

Our individual and collective CVs

We want to stop the war!

Bring the troops home now!

(Some in the peace movement

Claim their efficacy

In ending the war in Vietnam

But don’t mention the Vietnamese resistance of thirty years)

We used to crave media attention

Now we get validation via social media

We don’t want to be losers

We want to be a force to be reckoned with

Berrigan (like Gandhi)

In and out of jail

Visiting the poor who have cancer

Befriending the people with AIDS

Comforting the afflicted

Afflicting the comfortable

Renouncing the fruits of action

Giving everything to the work at hand

This page is part of my book, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.