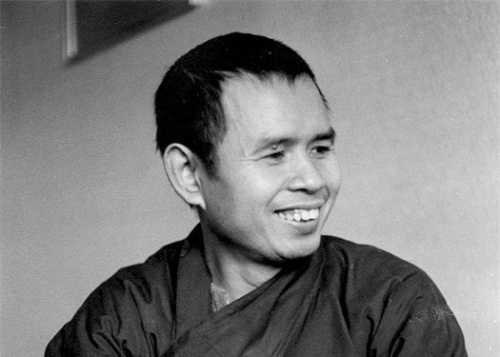

On Thich Nhat Hanh, At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk’s Life. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 2016.

Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh is a survivor. Narrowly missing death in South Vietnam on more than one occasion during the 1960s, he had many students killed in the bloodshed during the American War. He and other Tiep Hien Buddhists could not return to their country for fear of persecution, or worse. Uprooted, he ended up living in France, where he and friends slowly began to rebuild their lives.

At Home in the World, published in 2016, offers snapshots of nine full decades of Thich Nhat Hanh’s life. It bears keeping in mind that his country was living under a French colonial occupation regime, followed by U.S. intervention and invasion. He and his friends knew what it was like to live under the U.S. bombs.

Nhat Hanh admits that in his youth he was a “revolutionary monk.” He and his brothers wanted to rejuvenate Vietnamese Buddhism, and they had to reckon with a conservative religious establishment. Their motivation was simple: “Taking action against injustice is not enough. We believed action must embody mindfulness. If there is no awareness, action will only cause more harm. Our group believed it must be possible to combine meditation and action to create mindful action.” [41]

In the early 60s, Nhat Hanh was devoted to trying to stop the war, and he immersed himself fully in what needed to be done. One day, a young woman arrived to help out, and she shared “a basket of fragrant Vietnamese herbs, the various kinds of fresh greens that we eat with every meal in Vietnam.” This woman unwittingly called Nhat Hanh back to the refreshing and nourishing miracle of the herbs. He realized that he had been lacking balance and that to survive he needed to take time for such “healing wonders.” [53]

When he came to the US in 1966 to present the Vietnamese yearning for peace, he met and became friends with Martin Luther King. They both agreed that the “true enemy is the anger, hatred, and discrimination that is found in the heats and minds of man.” King nominated Nhat Hahn for the Nobel Peace Prize, which he had won in 1964. Like many people in the U.S., he was beside himself when King was assassinated. Out of this suffering, Nhat Hanh vowed to nurture and further King’s “beloved community.” [72]

Nhat Hanh knew many people who were prisoners of conscience under the both the Saigon and Communist governments. One man was sent to a “reeducation camp,” where he continuously practiced mindfulness in difficult circumstances. The Buddhist monk was impressed that when he finally had done his time, “his mind was as sharp as a sword. He knew that he had not lost anything during those four years.” [74]

Like his predecessors, the current U.S. president acts with imperial arrogance and presumptive impunity. Fifty years after the U.S. viciously bombed Southeast Asia, it continues bombing West Asia with a similarly delusional conviction that its intentional devastation will somehow get the enemy to beg for mercy. At Home in the World can be our vade mecum, reminding us of countless daily opportunities to extend ourselves to others, to cultivate community, to be in touch with ordinary miracles, to see our home as the present moment, and to be gentle and fierce bodhisattvas. [171]