for

Lindsey Trout

Danielle Mackey

Katie Madges

Katie Consamus

Magan Wiles

New Yorkers all

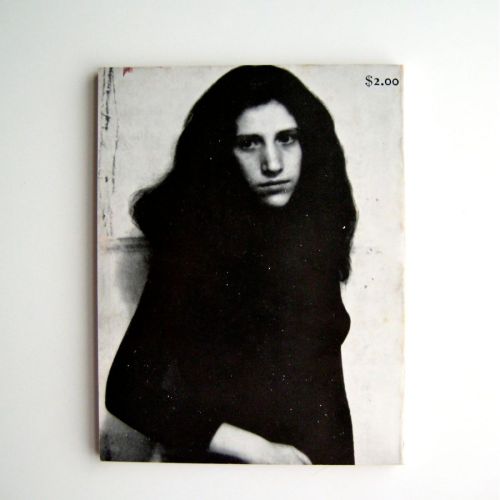

As some of you know, I have recently taken to the writing of Diane di Prima. You know this because I’ve called your attention to one or another of her poems that I love (Life Chant, Where Are You, Clearing the Desk, Keep the Beat) and her incendiary collection, Revolutionary Letters. This week I want to call attention to her memoir, Recollections of My Life as a Woman. Over 400 pages, it covers her early life to the later 1960s (she’s still alive, but I doubt that there’s a volume two coming). For my younger women friends who’ve grown up thinking “I can do whatever I want,” di Prima’s book will give you some historical perspective. For anyone in the various fields of art, Recollections will inspire you on your path (her sheer tenacity). For writers in their 20s or in their 70s, di Prima will remind you of what you need to hear.

Di Prima is calmly blunt, reminding me of Allen Ginsberg’s maxim, “Candor ends paranoia.” On male violence: “When I got older, what I heard from lovers, was that I was a controlling or castrating bitch. But—the assault was universal and ceaseless. You would have to be dead not to try to stop it for a minute.” Her Italian father: “If you were Italian, growing up in my house, your father handed you Machiavelli to read. To help you understand history, he told you. One of the only books he had besides Shakespeare and the encyclopedia. He read you Julius Caesar to show you how Mark Antony manipulated the crowd. What propaganda was. You never forgot.” On college: “I have no problem with leaving school. It is a hated and unfulfilling place, where I am studying nothing I care about. Where there are no powerful women teachers. No powerful teachers at all. No ideals, intensity of intellectual life. Nothing I’d hoped for. I am more than ready to leave, to get on with my life. Wherever it might take me.” What she never said to her mother: “Dear Mom … When are you going to tell me what was stolen from you? When will you name your oppressor?”

What is most compelling, though, is her relentless commitment to the path of writing. It had nothing to do with seeking fame, status, money: “Dear friends and companions of the holy art—the sacred task of pushing the container: how far will it go, the language, the form, the mind?” Disenchanted with Swarthmore College, she left and moved to the Lower East Side for no other reason than to be a poet. When she became pregnant, she imagined a response from John Keats who had inspired her in high school: “You have said nothing will be as important to you as Poetry. And yet you now plan to have a child, a child who will certainly come first in your heart. In your life. There will be no time, no energy for the work. He made it clear I was breaking a sacred vow.” But di Prima was up to the challenge: Both family and poetry were/are her lifetime priorities.

In addition to poetry, di Prima was committed to the theater in New York City. She and her companions, colleagues, lovers, couch-crashers were in it for the long haul: “Do you see? It wasn’t just the work, though the work was clearly blessed. Nor the rewards, which were none, as far as we knew. It was the life itself—a vocation, like being a hermit or a samurai. A calling. The holiest life that was offered in our world: artist. One that required the purest flame, clear lines of demarcation. Renunciation.” Lest you think her sense of the artist is too rarefied, the day to day was simple: “[it] entailed a continuous and seemingly endless rhythm of editing, typing, proofing, printing, collating, stapling, labeling, and mailing.” Relationships, politics, love, drugs, literature, suffering, poverty: “everything we had was grist for the mill. To keep the theatre open, the presses running. To keep the new work flowing, and flowing out, so that it would communicate to those others who really mattered: fellow artists, fellow experimenters and risk-takers.”

I’ve facilitated many writing classes since 2012. I’ve always been amazed and inspired that so many people come, sit down, write with verve, share, listen, post, week after week. In her youth, di Prima had her practice: “Nulla dies sine linea. I will write on the covers of my notebooks. No day without a line. A new commitment. Purpose. It was as if I remembered why I had come here. Fallen to earth. All the day’s minutes focused toward an end, and the end was: to sit quietly with my notebook somewhere. Watch words fill out the lines, as the pen moved. Mind moved and heart. And lips. Strings of my voice.” Whether in New York or California, increasingly in touch with the nascent counterculture, she observes, “Through it all I wrote constantly: notebook, typewriter, letters. Wrote every day once again as I had in high school. With joy and abandon I found the poet again, the vision from which I started. ‘I am certain of nothing, but the Holiness of the Heart’s Affections, and the Truth of the Imagination’” [Keats]. But di Prima, too, had her doubts about her identity as a writer, especially given the “professional” scene inhabited by many of her male friends. But she came to this realization: “What I discovered that autumn at Stinson Beach was that each morning, after the routines of dressing and feeding the kids, and eating breakfast, I would simply and without forethought find myself at the window looking out at that small garden and writing on Whale Honey. So that it simplemindedly dawned on me over time that maybe that was all there was to it: maybe, just maybe, a writer was nothing more than someone who wrote. Gratuitously, and sometimes aimlessly, sat down and wrote—often without design. It was simply part of her life.”

May some of you become better acquainted with Diane di Prima. It’s always good to have elders, mentors, role models, disturbers of false peace, and visionaries in our lives to remind us: Go further.

1 Comment