On David Harris, Our War (Random House, 1996)

Today there exist tremendous and unprecedented possibilities for knowing the reality of our world just as it is, with all that it has in it of anti-kingdom and all the deaths it produces. As experience demonstrates, however, to know the world truly and to allow oneself to be affected by it, simple access to data is not sufficient, as abundant and trustworthy as the data may be, including those of the UNDP. Serious analyses are not sufficient either, not are truthful testimonies, as important as all these may be for other reasons. The reality of the anti-kingdom, its magnitude and its cruelty, can be truly grasped only by experiencing it in actu, in action, when it is actually dealing death. That is what is capable of moving people not only to laments, but to the struggle against the anti-kingdom.

–Jon Sobrino, El Salvadoran theologian

1.

Reading this book may make you repeatedly squirm in your seat, as much for the past it recounts as for the present it jarringly illumines.

David Harris was a draft resister during the Vietnam War. Protesting and resisting that war took a good ten years of his life, from 1965 to 1975. It took him twenty years before he could write and publish Our War. For Harris, it wasn’t just the troops’ war, or the politicians’ and generals’ war: It was the entire country’s. He argues that, as a nation, we have not reckoned with what we did in the former Indochina and what it did to us, our politics and collective soul.

And it’s unnerving to realize that sometime in the near future, another resister (a soldier, perhaps) may write a book called Our Wars, referring to the catastrophic U.S. occupations and disruptions into Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

2.

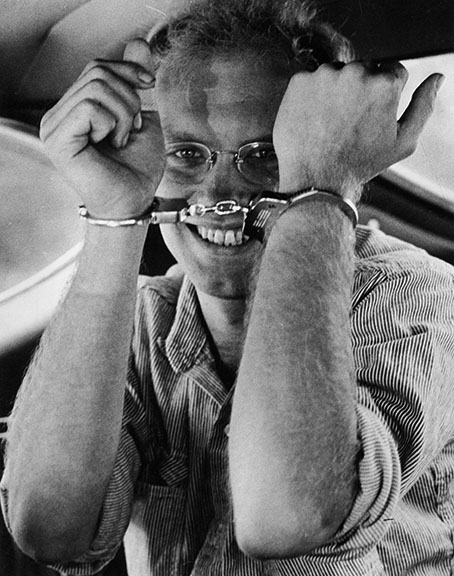

Harris was the All-American Boy. Student body president at Stanford University, he had the potential to achieve anything he wanted. But he paid attention to what had been going on in Southeast Asia since the early 1960s. By that decade’s middle, he had come to the conclusion that U.S. policy there was intolerable. Therefore, he attempted to put his body in the way of the U.S. killing machine.

He traveled relentlessly around the country to encourage other young men not to go. He gave over a thousand speeches and participated in hundreds of demonstrations. He spent two years in prison. Unlike “the best and brightest”—the men in Washington who planned, initiated, and deepened the war–he was outraged by its murderous devastation and sought to resist it with his whole being.

A common belief about the U.S. war in Vietnam is that it was a “mistake,” although it was said to be motivated by our traditional good will and honorable intentions. Harris’s disagreement couldn’t be stronger:

In this particular “mistake,” at least 3 million people died, only 58,000 of whom were Americans. These 3 million people died crushed in the mud, riddled with shrapnel, hurled out of helicopters, impaled on sharpened bamboo, obliterated in carpets of explosive dropped from bombers flying so high they could only be heard and never seen; they died reduced to chunks by one or more land mines, finished off by a round through the temple or a bayonet in the throat, consumed by sizzling phosphorous, burned alive with jellied gasoline, strung up by their thumbs, starved in cages, executed after watching their babies die, trapped on the barbed wire calling for their mothers. They died while trying to kill, they died while trying to kill no one, they died heroes, they died villains, they died at random, they died most often when someone who had no idea who they were killed them under the orders of someone who had even less idea than that. Some of the dead were sent home to their families, some were reduced to such indistinguishable pulp that they could not be recovered. All 3 million died in pain, often so intense that death was a relief. They all left someone behind. They all became markers visited by those who needed to remember and not forget. The loss was enormous, and “mistake” is no way to account for it. A course of behavior that kills 3 million people for no good reason cannot be passed off as something for which the generic response is Excuse Me. [15-16]

In his 1995 book, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara did apologize to Americans for the loss of American life in Vietnam. It is impossible, though, to imagine any American leader acknowledging the mass death inflicted on the Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians by the United States.

3.

What did the United States do in Vietnam that demands, even at this late date, a reckoning and accountability? According to Harris,

[u]nable to locate our guerrilla adversaries, we uprooted whole villages and evacuated them to bastions surrounded by barbed wire, almost always against their wishes. Since we were in control of both everything and nothing, we measured our success by how many people we were able to kill and announced those statistics on a daily basis. We created free-fire zones where we claimed the right to do anything we wanted to anyone found there without our permission. We burned the homes of people we suspected of helping the other side. We tracked our adversaries with a secret police network of political prisons and assassins. We often killed whoever aroused suspicion and asked no questions. Eventually, we barricaded ourselves in urban forts and attempted to drive the countryside to us. We marked off sections of landscape on the map and sent bombers to saturate the areas in the hope of making them inhabitable. Before we left, we had dropped some 250 pounds of high explosives for every single human being in that part of the Southeast Asian continent. We also occasionally raped, pillaged, killed for sport, and transported heroin. The first three crimes were usually spontaneous actions by individual soldiers that went virtually unpunished; the fourth was a de facto government policy. Everywhere we stayed for any length of time, young children scavenged our garbage dumps, old women sold us dime bags of heroin, and impoverished teenagers sold us blow jobs. [40-41]

We thought our interests had automatic precedence over anyone else’s. We thought we were civilized and they weren’t. We thought our purposes were sufficient cause to poison their countryside. We couldn’t fathom that getting rid of us would be sufficient incentive to mobilize millions of people to risk everything. We thought we could win concessions at the bargaining table that we had never won on the field of battle. We thought we couldn’t trust them but they could trust us. We thought that whatever we said was true just because we said it. We thought our government knew best. We thought our government would never tell us lies. We thought that if we escalated just a few more notches we’d have them right where we wanted them. We thought no one could match us toe to toe for a year, much less ten. We thought what they did to our prisoners was shameful but thought nothing about what we did to theirs. We thought our surrogate government, still with little or no support, could resist the force that had kicked our ass for years. We thought we could save face by leaving the war with the South Vietnamese army still in the field. We also promised to repair war damage and normalize our relations after the war was over when we never had any intention of doing so. [63-64]

We left three countries in ruin and for years acted as if the only issue arising from the war years was the fact that a few hundred of our troops were MIA and thus unaccounted for. Like Cuba after the Revolution’s overthrow of the U.S.-backed dictator, Vietnam paid a price for its triumph by facing years of a fierce U.S. economic embargo as well as the U.S. refusal to honor Nixon’s pledge of $3.25 billion in reconstruction.

4.

What still sticks in some Americans’ craw is that Vietnam is the first war we “lost.” Accustomed to being the winners, the righteous, the talented, the land of the free and home of the brave, Americans knew that they had the most formidable military machine in human history, and yet were unable to impose their will on the Vietnamese resistance.

There are lots of explanations, but the simple truth is that we ran into a group of people who brought considerably more seriousness to this fight than we did: they lived underground, the huddled in the jungle, they moved by foot and bicycle, they fought on a little rice and a little ammunition. They absorbed enormous punishment, bore great sacrifice, endured untold hardship, and fought us and all our war machines to a dead stop. If they survived, they fought until the whole thing was done, some for as long as a decade. They did not back off, and they held the field until we finally lost our stomach for the fight and went home. And not only did we lose, but we were poor losers. When we finally left, we left like a whipped dog, pissing on one last bush as we fled down the street. [172-173]

Nevertheless, the U.S. inflicted such vast ecological, infrastructural, and human damage during the war that post-1975 Vietnam posed no serious threat to other nations of becoming an inspiring example of independence and social development.

5.

It was a commonplace for liberals during the Bush years to decry that Administration’s policies, which supposedly created a terrible blemish on America’s moral standing in the world. One can only mouth such idiocies if one totally ignores our wars in Indochina, which spanned from the Truman Administration to the Ford Administration. Such commentators evidently can’t handle the truth of what we did and who we really were.

As it turned out, we got little of it right and almost all of it wrong, and our war was the proof. It was the wrong fight, at the wrong time, in the wrong place, against the wrong people, for the wrong reasons, with the wrong strategy, the wrong tactics, and the wrong weapons. It was the wrong approach, to the wrong situation, betraying the wrong motives, from the wrong perspective, with the wrong attitude, to the wrong end, using the wrong means, effecting the wrong result. It was both the wrong twist and the wrong turn, arriving inexorably, of course, at just the wrong moment. It was the wrong choice, the wrong answer to the wrong question, altogether the wrong way to take care of business. And it wronged just about everybody it touched: it wronged the wrong and it wronged the rest of us as well. [177]

And now, twenty years after we finally left the war behind, all that hasn’t changed. What remains is for us to finally engage in the public arithmetic and admit we had no right to have been there and no right to have done what we did and no right to continue pretending otherwise. [178]

But the pretending continued and eventually helped to facilitate the U.S. production and distribution of Iraqi corpses and refugees.

6.

Like their predecessors before them (Johnson and Nixon, McNamara and Kissinger), George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and Dick Cheney walk free and easy, now that they are out of office. Like many previously engaged but finally weary U.S. citizens after 1973, people today are in the process of forgetting what just happened and, even worse, ignoring the continuance and even expansion of Bush’s criminal policies by the current administration.

At the conclusion of his book, Harris offers these words for our past and present wars:

I still cannot listen to the whump of helicopter rotors without recalling now middle-aged evening news footage of American boys armed to the teeth, arrogant and terrified, leaping though the downdraft and into the tall grass, ten thousand miles from home. Most came back, many came back in pieces, and some didn’t come back at all. I remember, and, like many who lived through the war, I remain suspicious of power and have never regained much respect for the exercise of force. I still have little use for patriotic displays and no use at all for military conscription. I close my eyes and see wire-service photos of peasants in black pajamas huddling together in the hope of simply making it through the afternoon without being shot or burned alive, and I am still haunted by how easily we defiled and abused, devoid of reflection, hidden from ourselves by a veneer of geopolitics and a parking lot full of denial. [191]

- David Harris