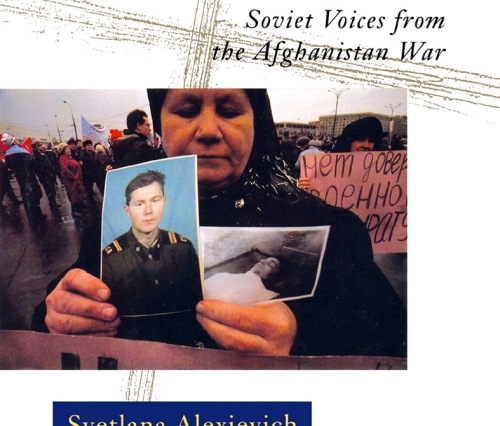

Svetlana Alexievich, Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, introduction by Larry Heinemann

Afgantsi (singular Afganets): Soviet veterans of the war

Even as Ken Burns’ new documentary on the Vietnam War airs, U.S. military forces have been in Afghanistan for almost sixteen years. While Burns will likely have some focus on the antiwar movement in the U.S during the 1960s, it’s sobering that there has been nothing like an antiwar movement for this war.

Svetlana Alexievich wanted to hear the bitter truths, so she went around asking listening, recording, and creating Zinky Boys, first published in the Soviet Union in 1990. Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015, Alexievich produced this work on the USSR’s Afghanistan War that even today can serve as a mirror to U.S. citizens or, in Kafka’s apt phrase,” an axe for the sea frozen inside us.”

What follows is a very small sample of the testimonies she evoked.

_________________________

The author: I ask myself, and others too, this single question: how has the courage in each of us been extinguished? How have ‘they’ managed to turn our ordinary boys into killers, and do whatever they want with the rest of us? But I’m not here to judge what I’ve seen and heard. My aim is simply to reflect the world as it really is. Getting to grips with this war today means facing much wider issues, issues of life and death of humanity. Man has finally achieved the ambition of being able to kill us all at a stroke. 10

A Private: One time, our column was going through a kishlak when the leading vehicle broke down. The driver got out and lifted the bonnet—and a boy, about ten years old, rushed out and stabbed him in the back, just where the heart is. The soldier fell over the motor. We turned that boy into a sieve. If we’d been ordered to, we’d have turned the whole village to dust. 16-17

A Soldier: They killed my friend. Later I saw some of them laughing and having a good time. Whenever I see a lot of them together, now, I start shooting. I shot up an Afghan wedding, I got the happy couple, the bride and groom. I’m not sorry for them—I’ve lost my friend. 6

A Private, Gunlayer: We didn’t want to know anything about anything. We were soldiers in a war. We were completely cut off from Afghan life—the locals weren’t allowed to set foot in our army compound. All we knew about them was that they wanted to kill or injure us, and we were keen to stay alive. 118

A Sergeant, Infantry Platoon Leader: You kill so you can get home. 71

A Nurse: That first March a pile grew up behind the hospital—a pile of amputated arms, legs and other bits of our men. Dead bodies with gouged-out eyes, and stars carved into the skin of their necks and stomachs by the mujahedin. 22

A Private: In those days no one had seen the zinc coffins. Later we found out that coffins were already arriving in the town, with the burials being carried out in secret, at night. The gravestones had ‘died’ rather than ‘killed in action’ engraved on them, but no one asked why all these eighteen-year-olds were dying all of a sudden. 15

A Civilian Employee: Yesterday a boy I know got a letter from his girlfriend back home: ‘I don’t want to be friends with you any more, your hands are dripping with blood.’ He ran to me and I held him tight. 75

A Major, Propaganda Section of an Artillery Regiment: We were ordinary boys and any other boys could have taken our place. When I hear people accusing us of ‘killing people over there’ I could smash their faces in. If you weren’t there and didn’t live through it you can’t know what it was like and you have no right to judge us. The only exception was Sakharov. I would have listened to him. 88-89

A 1st Lieutenant i/c Mortar Platoon: Did I kill anybody in Afghanistan.? Yes. You didn’t send us over there to be angels—so how can you expect us to come back as angels? 96

A Nurse: One junior lieutenant I know went back home and admitted it. ‘Life’s not the same now, I actually want to go on killing,’ he said. They spoke about it quite cooly, some of these boys, proud of how they’d burnt down a village and kicked the inhabitants to death. 24-5

A Doctor, bacteriologist: I can’t stand it back home either. It’s worse than over there. …So I want to move on again. I’ve applied to go to Nicaragua. Someplace where there’s a war going on. I can’t settle down to this life any more. 102

A Private: We were given medals we don’t wear and will probably return, medals honestly earned in a dishonest war. We’re invited to speak in schools, but what can we tell them? Not what war is really like, that’s for sure. Should I tel them that I’m still scared of the dark and that when something falls down with a bang I jump out of my skin? How the prisoners we took somehow never got as far as regimental HQ?… I can’t very well tell the school kids about the collections of dried ears and other trophies of war, can I? Or the villages that looked like ploughed fields after we’d finished bombarding them? 18

A Mother: I can’t carry on any longer, I just can’t. I’ve been dying for two years now. I’m not ill, but I’m dying. My whole body is dead. I didn’t burn myself on Red Square and my husband didn’t tear up his party card and throw the bits in their faces. I suppose we’re already dead but nobody knows. Even we don’t know … 32

A Mother: One of them was Goryachev, the Military Commissar. With what little strength I had left I threw myself at him like a cat. ‘You are dripping with my son’s blood’ I screamed. ‘You are dripping with my son’s blood!’ 123

A Mother: One phrase goes round and round in my brain like a gramophone record: ‘I’ll go wherever the Motherland needs me.’ 139

A Mother: It’s three years since my son died and I haven’t dreamt about him once. I go to sleep with his vest and trousers under my pillow. ‘Come to me in my dreams, Sasha. Come and see me!’ But he never does. I wonder what I’ve done to offend him. 140

A Mother: A lot of people came to the funeral but they kept silent. I stood there with a screw driver and wouldn’t let anyone take it away from me. ‘Let me see my son! Let me see my son!’ I demanded. I wanted to open the zinc coffin. 162

A Mother: Send me the worst imaginable pain and torture, only let my prayers reach my dearest love. I greet every little flower, every tiny stem growing from his grave: ‘Are you from there? Are you from him? Are you from my son?’ 180

A Widow: In the last war everyone was in mourning, there wasn’t a family in the land that hadn’t lost some loved one. Women wept together then. There’s a staff of 100 in the catering college where I work, and I’m the only one who had a husband killed in a war which all the rest have only read about in the papers. I wanted to smash the screen the first time I heard someone not television say that Afghanistan was our shame. That was the day I buried my husband a second time. 168

An Army Doctor: No one who went over there wants to fight another war. We won’t be fooled again. All of us, whether we were naive or cruel, good or rotten, fathers, husbands and sons, we were all killers. I understood what I was really doing—I was part of an invading army, let’s face it—but I don’t regret a thing. Nowadays there’s a lot of talk about guilt-feelings, but I personally don’t feel guilty. Those who sent us there are the guilty ones. 61

A Reader to the Author: Everything you wrote is true, except that the reality was even more terrible. I would like to meet you and talk to you. 188

A Reader to the Author: ‘Somewhere I read the confessions of an American Vietnam veteran. He said a terrible thing. “In the eight years since the war the number of suicides—officers as well as other ranks—is about the same as the number of fatalities in the war itself.” We must urgently consider the souls of our Afgantsi.’ 191

A Reader to the Author: ‘This is still a very painful memory. We were in a train, and a woman in our compartment told us she was the mother of an officer killed in Afghanistan. I understood—she was the mother, she was crying, but I told her, “Your son died in an unjust war. The mujahedin were defending their homeland.’” 192

A Private: What’s the point of this book of yours? What good will it do? It won’t appeal to us vets. You’ll never be able to tell it like it really was over there. The dead camels and dead humans lying in the same pool of blood. And who else needs it? We’re strangers to everyone else. 19