1.

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

–Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

2.

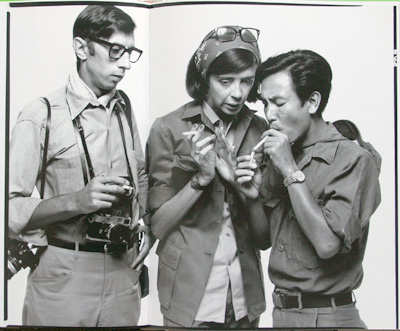

She had first traveled to Vietnam in 1955, glad to see that the U.S. was making good on its aspiration to set the world right. By her second visit in 1963, she had sobered up. Seven years later, she began a stint as foreign correspondent for the New York Times, and she had a hard time believing she was in the same country as before.

She had compassion and understanding for the U.S. troops, as she had for the Vietnamese being displaced, bombed, and killed by those same troops.

She knew she had privilege, of course; journalists could come and go, get the big story and give their careers a needed boost.

When she returned to the United States, she was obsessed. She admitted, “Turn the corner, people said to me in a kindly fashion. Forget the war. But I could not stop writing about it.”

And so she went to the out of the way places, to talk with ordinary Americans as to how the war had affected them. She learned that many Americans could not correctly say the name of the Vietnamese race. In a small Kentucky town, she asked the locals about their war dead, “Do you think that too much attention has been paid to the deaths in Bardstown?” She sought out American farmers, convinced that they, who so knew and understood the land, would care about the Vietnamese farmers being driven from their rice fields. She spent time with vets who had grown sentimental about Vietnamese women they had known but whose names they never learned. She met an antiwar activist: “He always wanted Americans to see the Vietnamese not just as victims but a people who loved their land, their trees, their poetry, their music, their language, their food. He thought the antiwar movement might have made a mistake in showing only the people in pain.” A veteran who participated in Dewey Canyon III in Washington told her that it was strange that the only people who seemed to be prosecuted for the war’s horrors were the wrong people.

She observed that as time went on and the war continued, Americans who had different views on the war seemed more contemptuous of each other than of the Vietnamese who were resisting the United States.

Her obsession was mirrored by the obsession of many of the people she met: vets, activists, people that could have been your next-door neighbors. One bureaucrat of the U.S. government who had worked in Vietnam did not appear to be obsessed; he told her, “the thing which I think I will remember about Vietnam when I am a hundred years old and will talk about it with my grandchildren is the countryside, how beautiful the women looked, and the food.”

After Gloria Emerson returned from Vietnam and spent three years roaming the country and interviewing her people, she published her project, Winners & Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses, and Ruins from a Long War (New York: Random House, 1977). Therein, she urged, “Let the books be written so when all of us are dead a long record will exist, at least in a few libraries.” In 1976 she saw that the war was already being quickly forgotten.

3.

Vietnam is just a confirmation of everything we feared might happen in life. And it has happened. You know, a lot of people in Vietnam–and I might be one of them–could be mourners as a profession. Morticians and mourners. It draws people who are seeking confirmation of tragedies….

Once I got so desperate-the Americans had started bombing Hanoi–I ran to the National Press Center where they give the briefings…a forty-year-old woman running through the streets in the middle of the night…and I wrote on the wall in Magic Marker, Father, forgive. They know not what they do. And I don’t even believe in God. Who is Father? Father, forgive, they know not what they do. But there were no other words in the whole English language.

If they found out it was me they would have sent me home. New York Times correspondents must not go running around at two o’clock in the morning writing, Father, forgive, they know not what they do. But afterward I thought how there’s no way…no one, no one to whom you can say we’re sorry.

–Gloria Emerson, April 1971

1 Comment