The Chasm between Them and Us

Kadya Molodovsky, A Jewish Refugee in New York: Rivke Zilberg’s Journal

Translated by Anita Norich

The accomplished Yiddish writer Molodovsky wrote this novel in serialized form in 1940-41, knowing obviously what was happening at the time to her friends and family in Europe. But it was impossible for her to imagine the eventual enactment of a “Final Solution.” We readers in 2019 know what was to happen in the years following Rivke’s arrival and year of adjustments in the U.S. This makes the author’s portrayal of American superficiality even more piercing and jarring. Yet this theme of clueless nonchalance also interrogates also our present: Besides the consistently awful headlines each day, what unimaginable catastrophe is looming around the corner?

***

The women talked a lot about themselves and didn’t give me the slightest opportunity to tell them how I came to be a refugee. 2

When he dances [like Benny Goodman] all I can think about is that my mother was killed by a bomb, and I don’t know what’s happening with my brothers, although I’m sure they’re not dancing now. I have no idea what’s become of my father either. I’d go to the ends of the earth to avoid Marvin’s dancing, but where can I go? 8

I thought they were getting ready for a Purim ball, but they explained that they were planning an event for war victims. I couldn’t believe how happy they were. They joked and talked and ate [cake]. No matter what’s going on, there’s always cake. If they’re having a card party—cake; a birthday—cake; collection for those suffering in the war—more cake. 12

And on top of everything else, I was upset with Red. When he came, I told him about my father’s letter. “You’re here, not there,” he answered. I could see in his face that he wasn’t the least bit concerned. Red saw that it upset me, and so he added, “What can you do?” I don’t know if Americans are heartless or they just pretend to be. I have no idea. They’re probably pretending. 50

“What are relatives nowadays? Once upon a time an aunt was an aunt, I brought everyone of my nieces and nephews to America. So now they make an appearance only if they need something.” 53

I’ve learned at least one thing in America. Whether things are good or bad, the first thing you have to do is smile. 65

She left to go get dressed. On Shabbos she always goes to the movies, and she didn’t want to be late. 91

Selma and Ruth were completely absurd in showing one another their makeup cases. 93

My uncle calls the cost of Selma’s wedding a “conflagration.” 114

Selma was very unhappy because [Mendl] chose such a terribly hot day to go to the hospital. 139

She was wearing seven gold necklaces, one under the other, so that her whole chest was covered in gold. She wears even more makeup than Selma: on her cheeks, her lips, her eyebrows, even her nose. 154

“In these times, when Jews are suffering throughout the world, we’re happy to be in America, and we’re proud to have such personages as Mr. Shamut.” 163

Even when I don’t think about my mother, I never forget her. And I never forget that my father is in Lublin sleeping on the ground in a barn or that Janet is blind. How can anyone forget all these things? But I’ve learned to keep quiet about it, to cover it up with white shoes, with factory work, and with living on Grand Street. Sometimes, if I laugh too loudly, I hear my laughter and am amazed. And in an instant, I’m more in Lublin than in New York. 166

***

Below his breath, the Jew asks of his gentile neighbor: “If you had known, would you have cried in the face of God and man that this hideousness must stop? Would you have made some attempt to get my children out? Or planned a skiing party to Marmsich?”

— George Steiner, “A Kind of Survivor”

My Canon

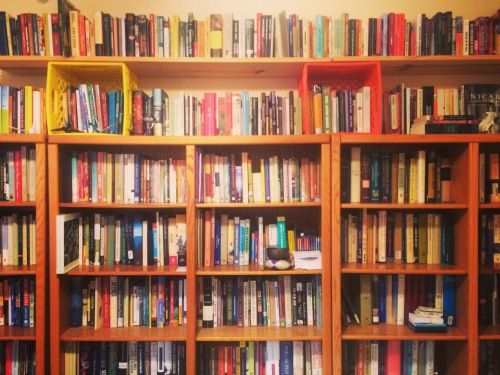

by Blair Hopkins

Mark Chmiel told me about the concept of the syllabus (books you are required to read for a given literature class) and one’s personal canon (books that have been significant to you personally, regardless of their literary status). This list is my personal canon, in no particular order. These are books I have either read more than once, or that I find myself thinking of and making connections to long after the fact, in some cases years and years after my reading of the book.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Eat Pray Love by Elizabeth Gilbert

Betsy and the Great World by Maud Hart Lovelace

Betsy’s Wedding by Maud Hart Lovelace

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Jekyll and Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

The Suicide Club by Robert Louis Stevenson

In Arabian Nights by Tahir Shah

The Caliph’s House by Tahir Shah

“Eveline” by James Joyce (short story)

An Acceptable Time by Madeleine L’Engle

The Arm of the Starfish by Madeleine L’Engle

The Joys of Love by Madeleine L’Engle

Persuasion by Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Emma by Jane Austen

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen

“Don’t Look Now” by Daphne DuMaurier (short story)

Rebecca by Daphne DuMaurier

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini

The Beautiful and Damned by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“The Birthday of the Infanta” by Oscar Wilde (short story)

“Antigone” by Sophocles (play)

A Long Fatal Love Chase by Louisa May Alcott

Lois the Witch by Elizabeth Gaskell

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” by Edward Albee (play)

“The Crucible” by Arthur Miller (play)

The Monk by Matthew G. Lewis

The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon by Richard Zimler

In the Wake of the Plague by Norman Cantor

Claire d’Albe by Sophie Cottin

Committed by Elizabeth Gilbert

The Wild Queen by Carolyn Meyer

In Mozart’s Shadow by Carolyn Meyer

Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie

The Last Day: Wrath, Ruin and Reason in the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755

–Blair took a Social Justice class with me at SLU in the summer of 2005

Books I’ve Given to Others

Woolf, The Common Reader, 2 v.

Roy, The God of Small Things

Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living

Kolsbun, Peace: The Biography of a Symbol

Proust, Cities of the Plain

Farmer, Partner to the Poor: A Paul Farmer Reader [3 people]

Young-Bruehl, Why Arendt Matters

Kerouac, The Dharma Bums: 50th Anniversary Edition

Easwaran, Gandhi the Man: The Story of His Transformation [several people]

Bei Dao, The Rose of Time: New and Selected Poems (Bilingual Edition)

Mahouz, The Cairo Trilogy [3 people, one in Ramallah]

Zamora, Riverbed of Memory

Washington, Haiku (Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets)

Proust, The Fugitive

Hachmyer, Alternatives to the Peace Corps: A Guide to Global Volunteer Opportunities [at least ten people]

Steiner, After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation [2 people, polyglots]

Musico, Cunt: A Declaration of Independence [3 people]

Nhat Hanh, Being Peace [let’s just say, “many”]

Bolaño, The Savage Detectives [thanks to Erin, at Left Bank Books]

Chomsky, The Essential Chomsky

Arendt, The Jewish Writings

Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (Pevear & Volokhonsky translation) [5 people]

Kerouac, You’re a Genius All the Time

Solnit, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities

Neruda, 20 Love Poems and a Cry of Despair

Cao Ngoc Phuong, Learning True Love: How I Learned and Practiced Social Change in Vietnam

Easwaran, Take Your Time: Finding Balance in a Hurried World

Gerassi, Jean-Paul Sartre: Hated Conscience of His Century, Volume 1: Protestant or Protester?

Zinn, Emma: A Play

Beavoir, Letters to Sartre

Roy, Field Notes on Democracy: Listening to Grasshoppers

Ophir, The Order of Evils: Toward an Ontology of Morals

Arenas, The Color of Summer

Follmi, Wisdom: 365 Thoughts from Indian Masters (Offerings for Humanity)

Fisk, The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East [3 people]

Proust, Swann’s Way

Arenas, El Color del Verano

Besancenot & Löwy, Che Guevara: His Revolutionary Legacy

Eliot, Middlemarch

Proust, Within a Budding Grove

Robertson, The New Laurel’s Kitchen

Johnstone, Impro: Improvisation and the Theater [4 people]

Barks, The Soul of Rumi [4 people]

El Libro de Mevelina [a couple score]

Aristide, In the Parish of the Poor: Writings from Haiti [5 people]

Slezkine, The Jewish Century

Brainard, I Remember [4 people]

Maurer, One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way [3 people]

Miller, Henry Miller on Writing

Wang, One China, Many Paths

Proust, The Guermantes Way

M., The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

Galeano, Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone

Cott, Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews [3 people]

Matisoff, Blessings, Curses, Hopes, and Fears: Psycho-Ostensive Expressions in Yiddish

Sachs, The Ninth: Beethoven and the World in 1824

Gilbert, Eyes in Gaza

Kidder, Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer [7 people, all pre-med]

Goldberg, Writing down the Bones [8 people, going back to 1988]

Zinn, The Bomb

Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Adonis, Selected Poems

Proust, The Captive

Nhat Hanh, Happiness: Essential Mindfulness Practices [3 people, at least]

Hirschman, Open Gate: An Anthology of Haitian Creole Poetry (Creole and English Edition)

Library of America edition, Walt Whitman, Poetry and Prose [2 people]

Waldman, Fast Speaking Woman: Chants and Essays [3 poets]

Ellsberg, ed. The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day

Proust, Time Regained

McQuade, An Unsentimental Education: Writers and Chicago [2 people]

Carson, A Truth Universally Acknowledged: 33 Great Writers on Why We Read Jane Austen

–In late 2010 a former student wanted a list of recommended titles. I decided to give her a list of books I saw fit, for one reason or another, to give to others.

What Is Vaster

In the early 1980s Harold Bloom noted about his experience of decades at Yale University that “[t]here is a profound falling away from what I would call ‘text-centeredness” among the current generation of American undergraduates, Gentile and Jewish alike. I can detect still some difference between Gentile and Jewish students in this regard, but it is not a substantial difference, and it seems to be diminishing.”

Bloom was on my mind after having read the stirring memoir by Aaron Lansky, Outwitting History: The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued a Million Yiddish Books. The subtitle is negated by Lansky’s own accounts of the many people—his own generation and those much older—who contributed to this undaunted retrieval of books. About text-centeredness, Isaac Bashevis Singer, the only Yiddish writer to win the Nobel Prize in literature, once imagined, “I’m sure that millions of Yiddish-speaking ghosts will rise from their graves one day and their first question will be, ‘Is there any new book in Yiddish to read?’

”

Lansky states early on in this tale of recovery that “[t]he books we collect are the immediate intellectual antecedent of most contemporary Jews, able to tell us who we are and where we came from. Especially now, after the unspeakable horrors of the twentieth century, Yiddish literature endures as our last, best bridge across the abyss.” After all of the envisioning, phoning, hustling, dumpstering, driving, loading, unloading, shelving, fund-raising, and refusing to give up, an institution arose, the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst.

Why did Yiddish matter so much to Lansky, who didn’t grow up in a Yiddish-speaking household? Here’s one reason: “If you read enough of Peretz and the countless Yiddish writers who followed, a deeper vision begins to emerge: of a Jewishness infinitely more interesting, more challenging, and more relevant, rooted in tradition, shaped by marginality, fueled by a relentless dialectic, and unafraid of the inextricability of art and action. If anything, Yiddish books are more of a counterculture today—more of a challenge to mainstream values—than they were when they were written.”

I can attest to the vision of one Yiddish writer whom I read in translation, from Joseph Leftwich’s anthology, Great Yiddish Writers of the Twentieth Century. Melech Ravitch’s essay, “Why Not Canonize a Second Book of Books?” has this passage: “A Bible is not an anthology, nor a history, nor a collection of documents. It is all of these together. The most important thing in a Bible is the bold, courageous, manly, human idea—the flowing line, not the precise dot. And the line is that man is good, and that absolute justice does exist, and that it will one day prevail; and that the Jews work for it and suffer for it, and though they often suffer more for it—for absolute justice— they don’t stop working for it, work more for it, in fact.”

In a recent article “What I Wish People Knew about Yiddishists,” Rokhl Kafrissen writes, “Learning Yiddish was the key that made so much of my own life make sense and provided me with a deep connection to history that hadn’t been part of my Long Island childhood.” Her articles are an inspiring and galvanizing introduction to and exploration of “dynamic Yiddishkayt” in communities coming together over texts, music, and theatre.

Emmanuel Levinas commented on his teacher, Shoshani (who was also significant in Elie Wiesel’s life): “[he] didn’t teach piety; he taught the texts. The texts are more fundamental—and vaster—than piety.” The texts Levinas had in mind likely did not include Y. L. Peretz. Nevertheless, the projects of Lansky and younger generations are contributing to the possibility of some people reconnecting to a vast (counter)cultural wealth. And for many, it may start, as Rokhl Kafrissen urges, with the alef-beys.

An Example of Kafka’s Ax

6 September 2009

Dear Randa,

Given how busy you must be, I can’t imagine that you would have brought along with you Robert Fisk’s The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. I regret that we didn’t have nearly enough time to discuss this book while you were here in St. Louis, so I thought I would send you an occasional “rereading” of that heart-breaking, illuminating, and disturbing tome. Perhaps next summer we can resume such discussions in cafes around St. Louis.

Since his youth, Fisk had long aspired to be a foreign correspondent, and he mentions that when he was 29, he received a letter from one of the higher-ups at The Times, in which he was told: “Paul Martin has requested to be moved from the Middle East. His wife has had more than enough, and I don’t blame her. I am offering him the number two job in Paris, Richard Wigg Lisbon—and to you I offer the Middle East. Let me know if you want it… It would be a splendid opportunity for you, with good stories, lots of travel and sunshine…” [xix]

In Fisk’s preface, he quotes Israeli journalist Amira Hass as saying that the journalist’s role is to “to monitor the centers of power,” the power that invades other countries, the power that sends people to be tortured, the power that conceives of genocide and implements it, the power that draws borders of the lands of others in its interests, the power that is drunk with its own dizzying rhetoric of rectitude, the power that predictably invites “blowback,” the power that acts as if it is above the law, with a quasi-divine right to disturb the lives and worlds of others.

This book is the product of thirty years of covering the Middle East, and Fisk has confronted what many of us here in the U.S. could hardly imagine, for example, “The Iraqi soldier at Fao during the Iran-Iraq War who lay curled up like a child in the gun-pit beside me, black with death, a single gold wedding ring glittering on the third finger of his left hand, bright with sunlight and love for a woman who did not know she was a widow. Soldier and civilian, they died in their tens of thousands because death had been concocted for them, morality hitched like a halter round the warhorse so that we could talk about ‘target-rich environments’ and ‘collateral damage’—that most infantile of attempts to shake off the crime of killing—and report the victory parades, the tearing down of statues and the importance of peace.” [xvii] He also observes, “[Governments] want their people to see war as a drama of opposites, good and evil, ‘them’ and ‘us,’ victory or defeat. But war is primarily not about victory or defeat but about death and the infliction of death. It represents the total failure of the human spirit.” [xviii]

In a letter to a friend, Franz Kafka once wrote that “If the book we are reading does not wake us, as with a fist hammering on our skulls, then why do we read it?” Fisk’s book is a heroic effort to wake us from our ignorance and indifference.

I hope you are not too weary from your travels and I look forward to reading about the work you are doing. I am sure you miss your family and friends, especially during Ramadan, but know this: Your vivacity and kindness are much missed here as well.

Until soon,

Dr C

–Randa took Social Justice with me at SLU in the spring of 2006.

“Born Only Yesterday, and Already

She Speaks Like a Perfect Mensch”

Dear Dianne,

I think this is the fourth time I’m reading Meshugah. It was originally serialized in the Yiddish Daily Forward. Because I’m reading it with you, and because Hedy is on our minds, in our hearts, I am paying more attention to the voices, the dialogue this time around. I marked the following passages, see what you think. Imagine twenty-five-year-old Hedy amidst such characters in NYC in 1949!

MA= Max Aberdam

AG = Aaron Greidinger

IS – Irka Shmelkes

M = Miriam

P = Priva

“Don’t be frightened, I haven’t come back from the Great Beyond to strangle you!” MA

“I’m alive, I’m alive.” AG

“You call this living?” MA

“My friend, I may have lost everything, but a bit of sense I still have. Though I’m in debt over my head, I owe nothing to the Almighty: as long as He keeps sending us Hitlers and Stalins, He is their God, not mine.” MA

“Where have you been all during the war?” AG

“Where have I not been? In Bialystok, in Vilna, Kovno, Shanghai, later in San Francisco. I experienced the full range of Jewish woes.” MA

“In all America you cannot get a decent cup of coffee. Hey, waiter! I ordered coffee, not dishwater!” MA

“In New York I found I was home again—they are all here, our people from Lodz and Warsaw.” MA

“I live on pills and faith—but not in God but in my own crazy luck.” MA

“Most of my clients are women, refugees from Poland who haven’t learned to count in dollars. They were driven half-mad in the ghettos and concentration camps.” MA

“The world is turning meshugah. It had to happen.” MA

“How many troubles I’ve endured because of these infatuations, and how much sorrow I‘ve caused only He knows who sits in Seventh Heaven and torments us.” MA

“A visit from Aaron Greidinger himself! For her you’re only one rung below the Almighty.” MA

“You can divorce a wife, but with an institution you are stuck. She swears that in Russia she stood in a winter forest at twenty degrees below zero and sawed wood.” MA

“Don’t joke, Max. My thoughts at night are poison.” P

“She came here after the war, in 1947. She speaks an excellent Yiddish. She knows Polish and German and speaks English without an accent. What she has lived through she will tell you herself.” MA

“Every Jewish family in Poland has its own saga to tell. But we ourselves are mad, and are driving the world to madness. Taxi!” MA

“These people are careful with their money, but they are also stingy—frightened that today or tomorrow famine will spread over America.” MA

“Our Jews are always the first in the line of fire. They simply have to redeem the world, no more and no less. In every Jew resides the dybbuk of a messiah.” MA

“People who have known hunger consider food the greatest blessing.” MA

“Our Yiddish men of letters do not respond to their mail. Some of them, perhaps, cannot afford the postage.” IS

“Flowers again? Oh, I shall have to kill you!” M

“I want you to know that I’m your greatest fan in the whole world. I read every word you write.” M

“How do you like that? Born only yesterday, and already she speaks like a perfect mensch.” MA

“Well then, I am done for already. What do they say in America—my goose is cooked. Let him say about me whatever he wants. After I’m dead you can both cut me up and feed me to the dogs.” MA

“I was nine at the time and reading Yiddish books. My mother scolded me. She said, ‘If you keep reading these books, you’ll grow old before your time. You may also forget Polish.’ I promised not to read them, but as soon as she left my room I returned to them. Whom did I not read? Sholem Aleichem, Abraham Reisen, Sholem Asch, Hirsch Nomberg, your brother Segalovich.” M

“I asked you what it was that you wanted to be?” AG

“What did I not want to be? Rockefeller, Casanova, Einstein…” MA

“I don’t know how it is with you, but I am quite willing to do without God, His wisdom, His mercies, the whole religious paraphernalia that goes with Him.” MA

“Really, Max, you are wrong. We Jews must never entertain the notion that there is no morality in the universe and that man may do whatever he likes.” M

“I did it in remembrance of my parents and my heritage. One can be a Jew without believing in God.” MA

“If God were to grant me one wish before I die, I would ask that you and Max move in with me, so that we three could be together.” M

“You are too young to be speaking of death.” AG

“Too young? I have stared death in the face for years.” M

“For me the whole world is an insane asylum.” AG

“For these words I must kiss you!” M

“I read everything I can find about Jews and Jewishness. I am especially fond of Yiddish. It is the only language in which I can express exactly what I want to say.” M

“You left Poland in the thirties, but I went through all the seven hells, as my grandmother used to say. If I could tell you what I experienced, you would not need to invent things.” M

A Late Night Raid on Victor Terras’s

“A Karamazov Companion:

Commentary on the Genesis,

Language, and Style of Dostoevsky’s Novel”

for Cami

“I love Russia, Aliosha, I love the Russian God, though I am a scoundrel myself.”

–Dmitry Karamazov

So, maybe you’ve already taken the plunge back in Wisconsin, and are now immersed in “A Nice Little Family.” I salute you, I envy you, and I may even give in to temptation—once again—to rereading it myself. I read Terras’s book back in 2005 (the 5th or 6th time), and I now scrounge around in my notes to indulge in the joy of landing on this and that, my mischief for mishmash, all for your amusement and excitation——-

***

Swann said in v. 1 of Marcel that there are really only 4 or so books that matter in one’s life; better to spend one’s reading time with these than ephemera like journalism.

FD is like Dmitri: Worst of all is that my nature is base and too passionate: everywhere and in everything I go to the limit, all my life I have been crossing the line.” 40

Levinas: Zosima: “no one can judge a criminal, until he recognizes that he is just such a criminal as the man standing before him, and that he perhaps is more than all men to blame for that crime.” Book 6, chapter iii, h.

Treat all students like Aliosha would, or Buddha.

Mona = volshebnitsa = enchantress 293

Bodhisattva: “everyone is really responsible to all men and for all men and for everything” 369

Details of an imitatio Christi are projected upon all positive characters, while the negative characters are inevitably enemies of Christ. A belief in personal immortality via resurrection in Christ resolves the question of suffering and injustice in the world. [Thanks, a nice theodicy…]

FD was trying to create an individualized “amateur” narrator, remarkable more for a certain ingenuous bonhomie and shrewd common sense than for sound logic, an elegant style, or even correct grammar. Xiv

Stylistic effects: emphatic repletion, parallelism, key words, accumulation of model expressions, paradox, catachresis.

Death of FD’s son in 1878, his pilgrimage to monastery of Optina Pustyn 3

“There is a novel in my head and in my heart, asking to be expressed.” 5

The major difficulty lay in the formidable problems involved in the realistic presentation of a moral and religious ideal. 7

“The last chapter (which I shall send to you), ‘Cana of Galilee,’ is the most essential in the whole book, and perhaps in the whole novel.” 7

FD’s long time project of a “novel about children” 8

“The main problem… is one that has tormented me consciously or unconsciously all my life – the existence of God.” 11

BK is “written in the margins of other books” 13

Pushkin’s little tragedies are felt throughout the novel; theme of man’s usurpation of divine power and the eventual collapse of that rebellion. 18

Scripture sources: Book of Job; 2 Thessalonians 2: 6-12 – the ultimate frame of reference for Grand Inquisitor; John 12:24; Jesus’ temptation – Matt. 4:1-11; Luke 4: 1-13.

Alyosha is a new version of Myshkin.

Words of consolation about the death of a child. 27

A man FD met in prison. But it’s only a nucleus and only literary connections and creative additions to this nucleus make Dmitry the unforgettable character he is. 28

“These blockheads have never dreamed of a denial of God which has the power that I put into the ‘Inquisitor’ and the preceding chapter, to which the whole novel is my response. I certainly do not believe in God like some fool (fanatic). And these people wanted to teach me and laughed at my backwardness!” 39

FD is like Dmitri: “Worst of all is that my nature is base and too passionate: everywhere and in everything I go to the limit, all my life I have been crossing the line.” 40

In the world of BK even beauty is involved in an antimony: men who are receptive to the beauty of Madonna may yet—and at the same time—pursue the beauty of Sodom. 42

The presence of God in the world (and therefore man’s encounters with God—or with “other worlds”) is the philosophic leitmotif of the novel. 43

One critic sees three bros as a dialectic structure with Ivan (intellectual man) the antithesis of Dmitry (sensual, aesthetic man), and Alyosha (man of God, or spiritual man). 44

All the fam agree on one point: love of life.

BK is a hymn to life in its entirety 44

Dmitri is nearer to God than Ivan. Through suffering—which he has not sought but which he accepts humbly and almost joyously at times—he finds God, and love of humanity as well. 45 [I love Dmitri]

Cf. Reb Greenberg: pull the child from the fire: Ivan’s intellectual pride leads to sterility of solipsistic, theoretical existence. 46

FD’s famous dictum that he would stay with Christ even if he were proven scientifically wrong suggests no more and no less than a belief in the primacy of moral values over theoretical knowledge. 48

Ivan and Zosima are, however, in essential agreement about the state of the world. Zosima, like Ivan, is painfully aware of the suffering of innocent children. Zosima, believing in God and immortality, feels guilty before all creation and loves all creation, while Ivan, who denies immortality, is reduced to spite and lovelessness. Ivan uses the sufferings of children as a pretext for his revolt, while Dmitri’s dream about “the babe” leads him to a recognition of his responsibility to suffering humanity. 49

Ivan’s Grand Inquisitor really rejects miracle, mystery, and authority and proposes instead to meet man’s needs by magic, mystification, and tyranny. 50 [See Chomsky in Necessary Illusions—the propaganda system]

Ivan, who as the Grand Inquisitor professes a burning love of mankind, admits that he cannot love his neighbor… and knocks a drunken peasant into the snow to freeze to death. 51

Rakitin, a careerist divinity student, represents a lower form of Ivan’s idea. 53

Dostoevsky’s religious feeling and artistic tact forbid him to make any attempt at creating a “voice” for Christ: Christ is more than any man could possible express (John 20:31). [yet see Saramago] Dostoevsky’s silent Christ is the very opposite of the proud and majestic Inquisitor. More than anything else, He is the kenotic Christ of Tiutchev’s poem, quoted by Ivan, the Christ who appears to us in every hungry, thirsty, or naked stranger, in every sick man, and in every prisoner. 55

Ivan Karamazov does not want universal harmony at the price of the sufferings of children. Zosima affirms that “everyone is really responsible to all men for all men and for everything,” so that by forgiving the child’s tormentor we are only forgiving ourselves (Book Six, chapter ii[a]… 57

Breakdown precedes breakthrough: Suffering and death are necessary so that there can be resurrection. 58

Most of all, Zosima and Aliosha are free of the terrible self-consciousness and pride which consume Ivan Karamazov. Dmitry Karamazov discovers his freedom slowly and painfully. He keeps surprising us by doing the unpredictable thing: “Rakitin lies! If they drive God from the earth, we shall shelter Him underground. One cannot exist in prison without God; it’s even more impossible than out of prison. And then we men underground will sing from the bowels of the earth a tragic hymn to God, with Whom is joy”… 58

Aliosha becomes a father figure to a group of schoolboys, Dmitry’s rebirth is marked by his dream of “the babe,” and even Ivan, shortly before his collapse, saves the life of the drunken peasant whom he had earlier knocked into the snow. 61

Kolia K, a double of Ivan Karamazov’s, helps us to understand Ivan. The suffering of innocent children being the pivot of Dostoevsky’s theodicy, the stories of the suffering and death of two youngsters, Zosima’s brother Markel and Iliusha Sneiriov, are all-important: in both instances suffering and early death are shown not to be cruel and meaningless, but meaningful and edifying. 62

Ivan K has lost his faith precisely because he has elevated himself above the people. In this case, “the people” are not necessarily peasants, but are what Ivan, a modern intellectual, is not: human beings who are intellectually and morally humble enough not to set themselves above over the “common crowd.” Having separated himself from the people, the intellectual has also separated himself from the faith of the people, and so from God. 66-67

***

Look, I’m only up to page 66 and Terras’s book is over 400 pages. I will pause, it’s past my bedtime, though I may continue this in the near future unless I myself get all wrapped up in Dmitri and Grushenka’s suffering!

Lenny Bruce Confesses

This afternoon I was perusing Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made, and came across the following skit of Lenny Bruce about Christ and the Jews:

… you and I know what a Jew is–One Who Killed Our Lord. I don’t know if we got much press on that in Illinois— we did this about two thousand years ago—two thousand years of Polack kids whacking the shit out of us coming home from school. Dear, dear. And although there should be a statute of limitations for that crime, it seems that those who neither have the actions nor the gait of Christians, pagans or not, will bust us out, unrelenting dues, for another deuce. And I really searched it out, why we pay the dues. Why do you keep breaking our balls for this crime? “Why, Jew, because you skirt the issue. You blame it on the Roman soldiers.” Alright, I’ll clear the air once and for all, and confess. Yes, we did it. I did it, my family. I found a note in my basement. It said: “We killed him . . . signed, Morty.” And a lot of people say to me, “Why did you kill Christ?” “I dunno . . . it was one of those parties, got out of hand, you know.” We killed him because he didn’t want to become a doctor, that’s why we killed him.

This page is part of a book-in-progress, Dear Love of Comrades, which you can read here.